eBook - ePub

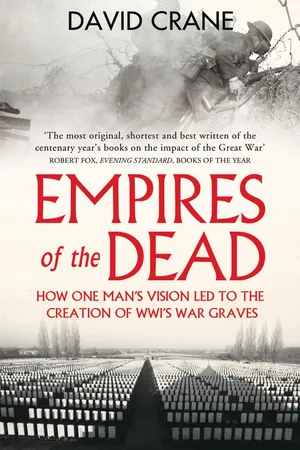

Empires of the Dead

How One Man's Vision Led to the Creation of WWI's War Graves

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Shortlisted for the Samuel Johnson prize for non-fiction; the extraordinary and forgotten story of the building of the World War One cemeteries, due to the efforts of one remarkable man, Fabian Ware.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Empires of the Dead by David Crane in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Commerce & Première Guerre mondiale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

CommerceSubtopic

Première Guerre mondialeONE

The Making of a Visionary

‘Now, God be thanked Who has matched us with His hour,’

RUPERT BROOKE

On the afternoon of Saturday 19 September 1914, a spare, dark-haired man in his mid-forties arrived at Lille in northern France to take command of the motley collection of vehicles and drivers that made up the British Red Cross’s ‘flying unit’. For the past four years he had been largely out of the public eye, but if there were few in the unit who would have recognised the face, they would undoubtedly have known the name of the man who for five turbulent years had been the erratically brilliant, ‘warmongering’ editor of the right-wing, imperialist Morning Post.

If they imagined that this was all that was to be said about him they would not have been entirely wrong – he did not idolise Napoleon for nothing – but it was by no means the most interesting thing about him. There were certainly men at the Morning Post who had only ever seen the bully in him, but Fabian Ware was a dreamer as much as a doer, as much a scholar and visionary as a bruising newspaperman. Which side of ‘this Rupert of the pen and sword’ had brought him to France would be hard to say.

It is very possible that he did not know himself, but if ever a man was made for France and what lay ahead, it was Fabian Ware. There are natural warriors who only come fully alive in battle, and then there is another, more alarming kind of man altogether: the romantic idealist and patriot who can glimpse among the horrors of war spiritual absolutes that the shabbier and greyer realities of peace deny; who can find in the call to sacrifice and suffering, in the democracy of death and the comradeship of war, not just a realisation of nationhood, but a healing balm for all the divisions, inequalities, subterfuges, and selfishness of ordinary political life.

For the best part of a decade Ware had been warning the country against the German menace, but then his whole adult life had been lived under the shadow of Britain’s decline. The generation before his that had grown up in the rich afterglow of Waterloo could reasonably expect to live and die in undisturbed possession of the world. It was Ware’s luck to take his place in public life at a moment when an era of expansive confidence and optimism gave way to that endlessly contradictory, paranoid, self-assertive and self-questioning Edwardian age, which would only finally come to an end with Jutland and the Somme.

It was an age of political paralysis at home and the naval race abroad, of gross inequalities and bitter industrial unrest, of national shame in South Africa and looming civil war in Ireland. But if these were the crises that shaped Ware’s politics something else is needed to explain the man. This is the history of an idea and not the biography of an individual, and yet when that idea so clearly bears the stamp of one man’s personality and moral convictions, we need at least some sense of what it was that would enable a middle-aged man to transform the random command of a small, volunteer ambulance force into an empire that would change the way a whole country would see and commemorate itself.

Fabian Arthur Goulstone Ware was born at Glendower House in Clifton, Bristol, on 17 June 1869, the third son of the second marriage of a prosperous member of Bristol’s Plymouth Brethren community and his schoolteacher wife. There is as little known of these early Clifton years as there is of his own married life, but if one was looking for a single clue to Ware’s character and development, one influence that, above all, made him the zealot and idealist he was, it probably lies in a childhood steeped in the Millenarian visions and theological rancour of Victorian England’s most combative, divisive and embattled Calvinist sect. It would be many years before Ware escaped the intellectual straitjacket of this world – years before he even ‘dared question what he had been taught to regard as the only conceivable premise for all thoughts and all actions’ – and in critical ways he remained the child of the Brethren he had always been. In adult life he seems to have achieved an amused and tolerant detachment from his Bethesda roots and yet, like many another Victorian apostate, his whole life remained a constant search for a faith or dream – Culture, Bloomsbury, Socialism, Industry, Philanthropy, Empire, Sex, Crusading Journalism, Women’s Rights, the alternatives were endless – that would provide a secular substitute for the religious certitudes and deep seriousness of the faith he had intellectually abandoned.

It was a powerful and energising legacy, and if the passion for battle, the conviction of righteousness, the love of autocracy also left their mark, these were only the reverse of that spirit of independence that is the great birthright of all Protestant dissent. In the most obvious sense, Ware’s whole life became a violent rejection of a sect that had turned its back against the world, but even when his work took him to the heart of the British establishment, he never sold out, never lost that critical power of detachment or sense of distance that, in the struggles ahead, would prove the most creative and important inheritance of his Brethren upbringing.

Even if Ware had wanted to ‘belong’ to that establishment world, his formative years and education inevitably reinforced a sense of apartness. In the late nineteenth century, the public schools and universities offered a well-trodden path to public service, but while his contemporaries were filling the reformed civil service and dying on Majuba Hill, soldiering with Stalky on the North West Frontier, or running the Empire, Ware was trudging down an obscure road that took him from a private tutor at home in Clifton to a struggling career as an indigent and ill-qualified schoolteacher. ‘My academic qualifications are not worth counting,’ he confessed in 1911, forced by the abortive hope of a post at Sheffield University to rehearse the long and dusty route that had brought him, at the age of forty-three, to the life of an unemployed ex-newspaperman working in Paris on a book no one was ever likely to read:

First class tutors up to eighteen (my people were Plymouth Brethren & took me away from a Preparatory School when I was twelve because I had been made captain of a cricket XI. I was never allowed to go back to school); then my father died & I had to earn my own living by teaching in private schools – I could only afford to work for a London degree – after having passed two of the three examinations I chucked it as I was getting no teaching, & saved up to come to Paris & took my Baccalaureate in science … Returning from Paris I was for several years assistant master in the Bradford Grammar School, then I reported to Sadler on foreign educational systems (Germany), was British Educational Representative at the Paris exhibition in 1900 and, when I came out … in 1901, was inspecting secondary schools for the Board of Education and was to be made a permanent inspector as soon as the inspectorate was established … All this counts for nothing among English academic people who smile at it all as they would smile at my Paris pinkish-mauve hood & cap of the same colour which is a cross between a coster’s headdress & a biretta!!

For an ambitious, sensitive and highly gifted idealist, there must have been endless frustrations, although in the long run this education opened up a richer and more varied experience than a conventional and insular English public school could ever have done. In the last decades of the nineteenth century, the life of a secondary schoolmaster was as miserable as it has ever been, but it crucially gave Ware the experience and right – a right he would claim in the pages of the Morning Post and again in France – to speak for that other Britain which, in the years ahead, would make up the Pals’ battalions and fight and die in their anonymous thousands in the mud of Flanders and the Somme.

If it was the years of educational drudgery and poverty that made an egalitarian and social reformer of Ware, it was the next phase of his career that hardened ‘pity and indignation’ into the kind of vision and ideal that was so crucial to a lapsed child of the Brethren. In 1900 he had published the first of two books on educational reform, and on the back of a growing reputation he went out to South Africa the following year to oversee the post-war reconstruction of education in the Transvaal alongside that famous ‘Kindergarten’ of talented and devoted young imperialists that the High Commissioner, Lord Milner, had gathered around him.

The figure of Viscount Milner has receded so far into the background of history that it is hard now to remember how large he once loomed over the Edwardian political landscape. Alfred Milner was born in Giessen, Hesse in 1854 of Anglo-German stock and received his early education at a Gymnasium in Tübingen. On the death of his mother in 1869, the fifteen-year-old Milner returned to England, and in 1872 won a scholarship to Benjamin Jowett’s Balliol, where a brilliant undergraduate career and a fistful of university prizes was rounded off with a First in Classics and a fellowship to New College.

This was the Oxford of Ruskinian high-mindedness and social intervention, of Arnold Toynbee and H. H. Asquith, of the Canadian imperialist George Parkin, and Cecil Rhodes – and it was the dominant influence on Milner’s life. ‘As an undergraduate at Oxford,’ he later wrote,

I was first stirred by a new vision of the British Empire. In that vision it appeared no longer as a number of infant or dependent communities revolving around this ancient kingdom but as a world encircling group of related nations, some of them destined to outgrow the mother country, united in a bond of equality and partnership, and united … by moral and spiritual bonds.

At the heart of Milner’s ‘New Imperialism’ was a quasi-religious belief in the innate superiority of the English ‘race’ and an unshakeable conviction of its civilising destiny, and one of the great tragedies of British history is that he found himself in a position to implement it. On leaving Oxford he had gained a formidable reputation as an administrator and public servant, and after a formative colonial apprenticeship in Egypt under Lord Cromer, he went with the blessings of all parties to ‘Southern Africa’ as High Commissioner and Governor of the Cape Colony at a time when the Jameson Raid and President Kruger’s treatment of British Uitlanders in the Transvaal had forced South Africa to the front of the political agenda.

It was a disastrous appointment – a crisis that called for cool pragmatism and the government had sent an imperial visionary, negotiations that demanded compromise and tact and they had sent the one man in England as obdurate as Kruger – and Britain reaped what it had sown. It is very possible that nobody could have dealt with Kruger and his dismal combination of ‘hatred’ and ‘invincible ignorance’, but Milner had never any intention of trying to find a peaceful answer to the problems of the Transvaal. When negotiations finally broke down in the summer of 1899 he had the war with the Afrikaner republics that he had wanted.

The Second Boer War was known as ‘Milner’s War’ for good reason. Milner was not a man to shy away from the personal or public opprobrium brought about by a brutal and ugly conflict. In the spring of 1901 he had returned to England to face down a storm of Liberal criticism from his old allies, but within the year he was back again with a peerage and the support of a Conservative government to tighten the final terms of the Boer surrender and begin the vast post-war task of reconstructing a united, reformed and anglicised South Africa along the imperial lines he had always dreamt of.

It was as part of this work of political, legal, economic and educational reconstruction that Fabian Ware went out to join the Kindergarten of zealous young administrators: men like Geoffrey Dawson, the future editor of The Times; Philip Kerr, Britain’s Ambassador to the United States at the outbreak of the Second World War; the novelist and future Governor General of Canada, John Buchan; the future Governor General of South Africa, Patrick Gordon; Lionel Curtis, the driving force of the ‘Round Table’, who shared Milner’s vision and would carry the Milner torch deep into the twentieth century.

For the first time in his adult career, Ware had the man and the faith he needed, and the substitution of the religio Milneriana for his father’s Millenarianism marks the great ‘conversion experience’ of his life. Under the influence of Milner’s ‘race patriotism’ he learned his sense of Britain’s global destiny, under Milner he honed his doctrine in the subordination of the individual to the collective, under Milner he gave political shape to his social conscience, and under Milner – cold, austere and ‘Germanic’ in public, generous and warm in private – he learned the virtue of public service that would be his own lodestar. ‘For you your job was your mistress, and was no step-mother to those who worked under you,’ Ware addressed him on the eve of the First World War in an open letter that is as close to a personal manifesto as he ever came,

You taught them to regard their own success as dependent on and inseparably associated with the success of their job. They rose, as it were, on the work which they built up, you, the supreme architect, from your lofty outlook warning off those evil fellows … who would have taken advantage of their absorption in their daily task to climb up, unnoticed on the growing structures and supplant them.

It was under Milner too that Ware got his first chance to show his own remarkable abilities as an administrator. The early months in South Africa produced a series of frictions that provide an interesting ‘taster’ of the battles ahead, but from the day he established his independence he was in his element, doubling within four years the number of children in education in the Transvaal, addressing the technical mining and agricultural needs of the newly annexed state, breathing in the heady fumes of imperialism, and battling – and no one loved a battle like Ware – with a Boer clergy so bigoted and intransigently hostile to reform or reason that even the Brethren could have learned a lesson from them.

‘I was working late last night,’ he would write to his old ‘chief’ from Paris in 1911, the memories of the Transvaal and their imperial venture as fresh and intoxicating after six years as if it had all been only yesterday,

& watched the sunrise – behind the Pantheon & the Bibliothèque Ste Genevieve – and whenever I see it, it reminds me of S. Africa & takes one by the throat as the French say … What a time it was & how we worked – & always when we were conscious of having done rather more than our hardest hoping that it would please you: I suppose I was a fool not to stay on doing your work. But as you say, it is no good regretting.

Ware might have been a fool not to have stayed, but as an ambitious man in his mid-thirties he would have been a bigger fool not to have left when, in 1905, he was offered the editorship of the Morning Post. The offer must have come as much of a surprise to him as it did to everyone else in journalism, but as the newspaper world soon found out, he was a born editor, the ideal man to take a hopelessly moribund Tory newspaper like the Morning Post and kick and bully and charm it into becoming the most influential and combative paper of its day.

The paper had no library or reference support for its journalists, no salaried leader-writers, no proper offices at this time, even, nothing but temporary wooden sheds near the Aldwych, and ‘a regular mythology of minor deities created by the old traditions’. ‘It is magnificent but it is not business,’ Ware wrote to the paper’s owner, Lord Glenesk, as he began the Augean task of modernisation,

I will take an example. The Art Critic is, I believe, actually bedridden. At any rate I have never seen him. He draws his salary and farms out the work. He does this with discrimination … But he breaks the first condition which should attach to such service and that is regular attendance at the office.

There was something else that he had learned under Milner that stood him in good stead in these early days at the Morning Post, and that was how to make use of that informal network of connections that held the British establishment together. The group of young zealots who had made up Milner’s Kindergarten had nearly all been Oxford men, and one of Ware’s first acts as editor was to write off to the Master of Balliol – Milner’s old college – to scout for talent. When the answer came back in the shape of ‘an ugly mannered but honest, self devoted young reformer of the practical kind called William Beveridge’, Ware took it and him in his stride. He asked me ‘to come on the staff completely to undertake all the articles and leaders on social questions!’ an astonished Beveridge – the future architect of the modern Welfare State – later wrote of their interview,

I told him of course that in party politics I was certainly not a Conservative and that in speculative politics I was a bit of a Socialist. He rather liked that than the reverse. I told him I wasn’t a journalist; he said there was no such thing as a journalist, that it was all practice. It was a flattering approach. I went about feeling like a beggar-boy who had just been proposed to by a Queen.

The change of regime was seldom as smooth or happy a transformation as this suggests, however. Although Lord Glenesk knew what ...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Contents

- Maps

- List of Illustrations

- Prologue

- 1. The Making of a Visionary

- 2. The Mobile Unit

- 3. With an Eye to the Future

- 4. Consolidation

- 5. The Imperial War Graves Commission

- 6. Kenyon

- 7. Opposition

- 8. The Task

- 9. Completion

- 10. Keeping the Faith

- Picture Section

- Footnotes

- Notes

- Select Bibliography

- Index

- Acknowledgements

- Also by David Crane

- Copyright

- About the Publisher