This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

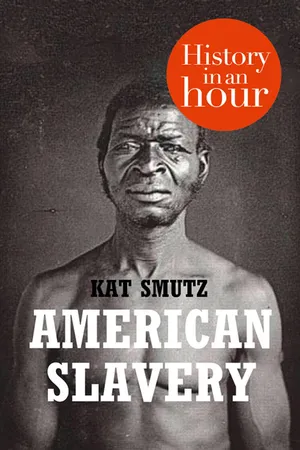

American Slavery: History in an Hour

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Love history? Know your stuff with History in an Hour.

From the first slaves arriving in Jamestown in 1619, the cotton fields in the Southern States and shipbuilding in New England, to the slaves who laid down their lives in war so that Americans could be free, American Slavery in an Hour covers the breadth of the subject without sacrificing important historical and cultural details.

An important and dark time in Black – and American – history, American Slavery in an Hour will explain the key facts and give you a clear overview of this much discussed period of history, as well as its legacy in modern America.

Know your stuff: read the history of American Slavery in just one hour.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access American Slavery: History in an Hour by Kat Smutz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia de Norteamérica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

HistoriaSubtopic

Historia de NorteaméricaAppendix 1: Key Players

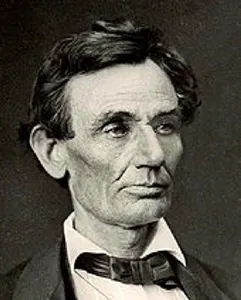

Abraham Lincoln (12 February 1809–15 April 1865)

Abraham Lincoln is possibly the figure most closely associated with the slavery issue in the United States, but slavery was not his primary concern when he was elected as the sixteenth president of the United States in November 1860. While he had made clear his opposition to slavery throughout his political career, he expressed the opinion on more than one occasion that he did not believe that African-Americans were equal to whites. He also supported colonization for the same reasons that Thomas Jefferson had – both men felt that African-Americans could not assimilate into white society.

Abraham Lincoln, photograph by Alexander Hesler

But the general consensus in the South was that Lincoln was a threat to their ‘peculiar institution’, and when he was elected to office many slaveholding states followed through on their threats to secede from the Union. Within months, the war that so many had foreseen and feared had begun.

Lincoln’s priority was preservation of the Union; the abolition of slavery was secondary. He made his position clear, stating that he would do whatever it took to preserve the Union, even if it meant preserving slavery, ending slavery, or finding common ground somewhere in the middle.

Frederick Douglass, a former slave who had educated himself and who advocated for the rights of slaves, met often with Lincoln to discuss equality for African-Americans, especially its soldiers. It was Douglass who encouraged Lincoln to provide equal pay, uniforms and armaments for African-American troops who fought for the Union.

While Lincoln is known as the man who ended slavery, in truth he was reluctant to do so. He felt that the Constitution did not provide for government to end the institution. When South Carolina was followed by ten other states in seceding from the Union to form the Confederate States of America, Lincoln refused to recognize it as a nation, saying that it was unconstitutional. He had declared martial law in some border states, states where slavery was still legal, but that hadn’t joined the Confederacy. Even though the Union had been divided, he was still hesitant to outlaw slavery for fear of losing the support of the border states. But finally, in 1863, Lincoln declared slavery illegal in the states that had seceded.

Lincoln was re-elected as president shortly before the war ended. Whatever plans he might have had in mind for rebuilding and reuniting the nation never saw fruition. While attending a production at the Ford’s Theatre on the night on 14 April 1865, a Southern supporter, John Wilkes Booth, who saw Lincoln as a tyrant, forced his way into Lincoln’s box and shot the president at point-blank range in front of his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln. The president lingered for several hours before dying on the morning of 15 April. The secretary of war, Edwin M. Stanton, is said to have saluted and uttered the words, ‘Now he belongs to the ages.’ Lincoln was the first US president to be assassinated.

Elijah Parish Lovejoy (9 November 1802–7 November 1837)

Elijah Parish Lovejoy was not the only abolitionist who died for what he believed in, but he is one of the better-known martyrs of the abolitionist movement. Lovejoy was murdered by a mob in Alton, Illinois, because he continued to publish abolitionist materials, even after his having press destroyed three times.

Elijah Parish Lovejoy, portrait by Jacques Reich

Tensions ran high in Saint Louis, Missouri in 1837. The city stood on the banks of the Mississippi River, dividing it the pro-slavery state of Missouri from the free state of Illinois. Lovejoy had criticized a local judge for his failure to indict anyone for the lynching of an African-American.

Lovejoy had moved his family and his press to Alton in 1836 and established the Alton Observer. Even though Alton was in a free state, it was still a focal point for slave catchers and slavery supporters because of its proximity to the slave state of Missouri.

On 7 November 1837, a mob of pro-slavery supporters approached the warehouse where Lovejoy had hidden his press. They opened fire on the building, and Lovejoy and his men responded in kind, killing a man named Bishop. The mob found a ladder and used it to set fire to the warehouse roof. Lovejoy and another man came out and pushed the ladder down before hurrying back inside. When the ladder was raised again, Lovejoy and his friend ran out again to push it down. This time, he was shot dead.

The local district attorney prosecuted the case, but failed to make a conviction. Abolitionists were outraged, and Lovejoy was elevated to the status of martyr.

After Lovejoy’s murder, his brothers Joseph and Owen wrote a memoir of their brother and his defence of the freedom of the press. Other honours to Lovejoy include a monument erected near his grave in Alton; and a local African-American community was renamed Lovejoy, as was a library at Southern Illinois University. The Elijah Parish Lovejoy Award is a journalism award given each year by Colby College; and Reed College annually awards the Elijah Parish and Owen Lovejoy Scholarship.

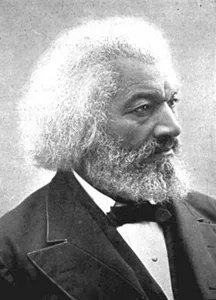

Frederick (Bailey) Douglass (c.1818–20 February 1895)

The title of Renaissance Man is probably the best way to describe Frederick Douglass. Born a slave and denied even the most basic education, Douglass rose to become a man of intelligence, principles and influence.

Frederick Douglass

Frederick’s mother was a slave named Harriet Bailey. The identity of his father is uncertain, but it is believed to be his mother’s owner, Anthony Bailey. While his mother worked in the fields, Frederick was raised by his grandmother. At the age of twelve, he went to live with a relative of his owner whose wife began teaching Frederick to read. When her husband learnt of it, he demanded his wife desist. Not only was it illegal to educate a slave, but it was believed that if a slave learnt to read, he might become dissatisfied with his lot in life and attempt to rise above it.

But Douglass had already obtained the rudimentary skills of reading and continued to teach himself using the Bible and newspapers.

In 1833, Frederick was hired out to a poor farmer named Edward Covey. Covey was known as a slave breaker and 16-year-old Frederick was whipped on a regular basis. On the verge of defeat, Frederick steeled himself and fought back. Covey lost the fight and could have sent Frederick to jail, where he would have been executed without trial. But Covey didn’t want anyone to know that he had been bested in a fight with a slave and so kept quiet.

After three attempts, Frederick finally managed to escape in 1838, and married a free African-American woman named Anna Murray. Before long, he became acquainted with abolitionists and earned a reputation as an orator, telling his story of slavery and escape to audiences all over New England, and later in the United Kingdom. It was while he was in Britain in 1847 that funds were collected to purchase Douglass’ freedom.

Douglass wrote three versions of his life under the name Frederick Douglass. He also owned and edited five newspapers, including the North Star. He was known as an orator, a social reformer and a statesman. During the American Civil War, he fought for the equality of black soldiers and supported women’s suffrage.

After the war, Douglass held several government positions, including US representative to Haiti. He was the first African-American to receive a vote for president of the United States from a major political party.

Douglass lost his wife, Anna, in 1882. He remarried in 1884 to Helen Pitts, a white feminist. The marriage was controversial, not only because of their difference in race, but also because Helen was twenty years younger than Douglass.

Douglass died in 1895 at Cedar Hill, a home that he had purchased in 1877. He and Anna had expanded the house from fourteen rooms to twenty-one, and purchased surrounding lots to expand the property to fifteen acres. Overlooking the Anacostia River as well as the city of Washington DC, the house is now maintained by the National Park Service.

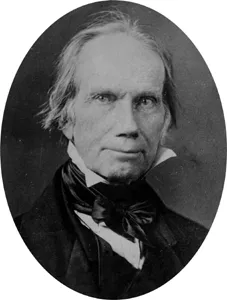

Henry Clay (12 April 1777–29 June 1852)

Henry Clay was known as an orator, statesman and peacekeeper. Born the son of a Virginia farmer, his father died when he was only four and left him heir to two slaves. His mother remarried and his stepfather moved the family to Richmond, Virginia where Henry worked first as a shop assistant, and later in the Court of Chancery. He showed an aptitude for law and received his legal education at the College of William and Mary. After being accepted to the Bar, he set up a law practice in Lexington, Kentucky in 1797.

Henry Clay

Clay’s legal skills led him to be interested in politics. In 1803, he was elected to the Kentucky General Assembly and advocated the state’s gradual emancipation of slavery. It was the beginning of what would be a long career in politics. Clay was appointed to various seats and elected three times to the United States House of Representatives where he served as Speaker of the House. He was the ninth United States Secretary of State and served four times as a United States Senator.

Clay watched as the balance of power between slaveholders and anti-slavery advocates swung back and forth, and feared for the growth and stability of the United States, a nation still in its infancy. In 1820, the Missouri Territory, part of the Louisiana Purchase, applied for statehood. Admission would mean that there would be twelve slave states to eleven free. In an effort to keep the peace in Congress, Clay proposed the Missouri Compromise in which Missouri would be allowed to enter as a slave state and the state of Maine would enter the Union as free soil. It also determined that any states north of the latitude 36 degrees 30 minutes would be free, with Missouri as the only exception.

Clay also prevented the South’s first threat to secede over the Tariff of 1828. The tariff was intended to help protect the industrial growth in the North, but it also put a financial burden on the agricultural South. The State of South Carolina refused to pay the tariffs and threatened secession. Matters grew worse until Clay managed to broker a deal in Congress to gradually lower the tariffs. It was a clear warning signal that tensions between the North and South over economics and slavery were mounting.

Clay also foresaw that admitting Texas as a slave state would increase tension over slavery and provoke Mexico into war. He would later propose resolutions known as the Compromise of 1850 to appease both North and South over expansion policies regarding slavery.

In spite of his heritage as a slave owner and representative of a slave state, Henry Clay served the Union until his death from tuberculosis in 1852 at the age of seventy-five. Senator Henry Foote of Mississippi said of Clay, ‘Had there been one such man in the Congress of the United States as Henry Clay in 1860–61 there would, I feel sure, have been no civil war.’

Jefferson Davis (3 June 1808–6 December 1889)

Born the son of a plantation owner in Mississippi, Davis spe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- About History in an Hour

- Introduction

- The New World

- The Middle Passage – the Atlantic Slave Trade

- The Human Cargo

- Welcome to the New World

- Non-Existent Rights

- The Abolitionists

- The Concept of Freedom

- The Educated Slave

- The Beginning of the End

- North v. South

- ‘Manifest Destiny’

- Uncle Tom

- John Brown

- Abraham Lincoln

- Secession

- The American Civil War

- The End of Slavery in the US

- Appendix 1: Key Players

- Appendix 2: Timeline of American Slavery

- Copyright

- Got Another Hour?

- About the Publisher