![]() SECTION I

SECTION I

PRACTICES BY EUROPEAN

RETAILERS![]()

Chapter 1

French Retailers and Sustainable Development

Laure Lavorata

Abstract

This chapter focuses on French food retailers and sustainable development. The food retailing groups can be divided into three types of distributors: integrated groups (Carrefour, Casino, Auchan, and Cora), groups of independent stores (Leclerc, Intermarché, and System U), and hard discounters as (Lidl and Aldi). In addition, in the sphere of more sustainable distribution, there are also specialized retailers such as Biocoop, Naturalia, La Vie Claire, and direct channels. These channels offer an alternative to the dominant model of industrialized and standardized agriculture and supply symbolized by mass distribution. The evolution of the discourse on sustainable development from 2005 to strategies proposing local products, bio products, and private labels shows that mass retailers have understood that taking into account the collective interest of society can be a source of significant differentiation in a fiercely competitive market. A supplementary finding of this chapter is the major strategic role of private labels in the implementation of retailers’ sustainable development policy: improving products, rethinking packaging policy, and formulating advice for consumers.

Keywords: France; food retailers; private labels; local products; sustainable development; discourse

Retailers, like all companies, are confronted with the notion of sustainable development. However, more than companies in other sectors, they are often faced by a recurrent image problem linked to their business model. Indeed, they very often find themselves caught up in a conflict between consumers, to whom they want to offer the greatest product diversity at competitive prices, and producers, which they are accused of driving out of business through their sourcing policies. Commitment to sustainable development can make the difference in “a competitive world where commercial battles are won on the terrain of the image” (Lipovetsky, 1992). This seems to be the case for retailing, characterized by a changing corporate environment and fierce competition, where differentiation advantages are increasingly rare. For example, Carrefour launched its “Carrefour Bio” (Carrefour organic) range in 1997, followed by “Pêche responsable” (responsible fishing) in 2005 and “Carrefour Agir” (Carrefour action) in 2006. But Monoprix was the first retail chain to advertise, in 2002, around the topic “development all right, but only if it’s sustainable.” If retailers are becoming aware of the need to include sustainable development or ethics into their strategies, it is because they are judged not only on their financial results but also on their societal performance: since May 2001 (article 116 of law no. 2001-420), the New Economic Regulations require French companies listed on the stock exchange to specify in their annual report the way in which they take into account the social/societal and environmental consequences of their business.

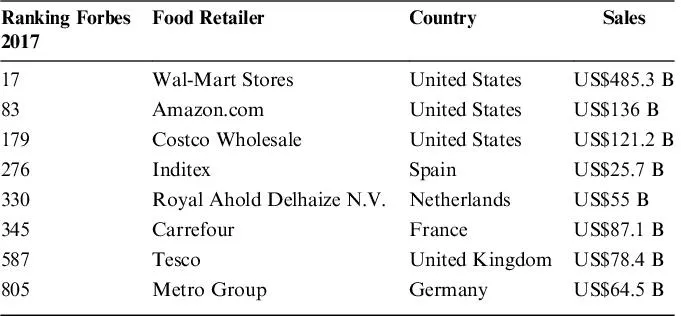

Moreover, the retail distribution sector has the economic power to play a key role in sustainable development, due to its financial importance, but above all due to the huge number of people it employs and/or involves, as an intermediary between producers and consumers. This increasingly concentrated oligopoly is globally dominated by one giant firm: Wal-Mart. In the Forbes ranking (Table 1), we can see its place among the most powerful companies.

Table 1. Ranking of Selected Retailers.

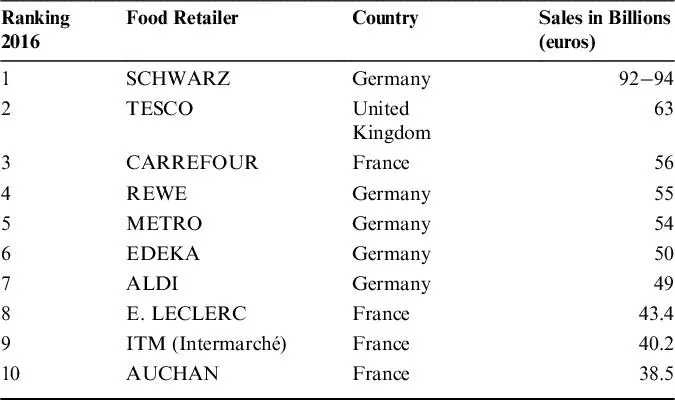

When focusing on Europe, the turnover of food retailers shows the large scale of this sector (Table 2) and the influence of three countries: Germany, France, and the UK.1

Table 2. Ranking of Food Retailers in Europe.

This overview gives us the situation of different retailers and the importance of specific European countries. This chapter will focus on France.

Presentation of French Food Retailers

The French food retailing groups can be divided into three types of distributors: integrated groups (Carrefour, Casino, Auchan, and Cora), groups of independent stores (Leclerc, Intermarché, and System U), and hard discounters such as Lidl and Aldi (Table 3).

Table 3. Market Shares of French Food Retailersa.

Food Retailers | Market Shares in France in October 2017 (%) |

Leclerc | 21.5 |

Carrefour | 20.7 |

Intermarché | 14.8 |

Casino | 11.8 |

Système U | 10.4 |

Auchan | 10.2 |

Lidl | 5.1 |

Cora | 3 |

Aldi | 2.2 |

Notes: ahttps://www.kantarworldpanel.com/fr

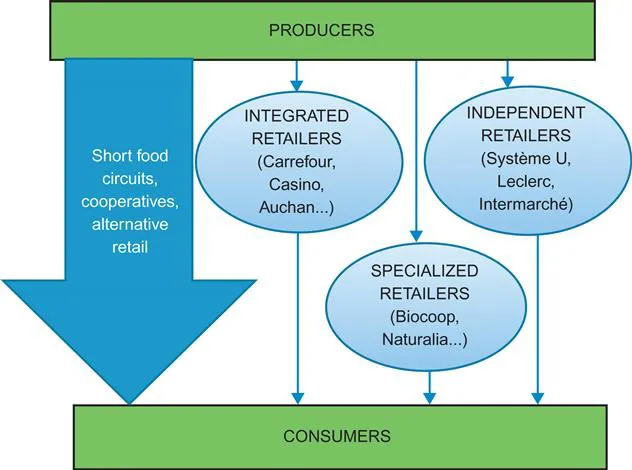

When studying sustainable development practices, we have to add specialized retailers such as Biocoop, Naturalia, La Vie Claire, and “short food circuits” (Figure 1). The first organic store in France opened in 1948, as a cooperative, which became Maison de la vie claire in 1965 and subsequently La Vie Claire in the early 1980s. Today, three organic chains dominate that market. The leader, in both turnover and the number of stores, is Biocoop, followed by Naturalia then La Vie Claire (Vernier & Zaidi-Chtourou, 2016). These specialist stores are currently facing growing competition from traditional retailers, attracted by the steep rise in the consumption of organic products, which are introducing organic product lines (Leclerc’s Bio Village products), specialized sections in stores or 100% organic stores (Carrefour Bio). A study2 indicated that 89% of French consumers bought bio products in 2016 and 15% consume these products every day. In 2003, 46% of French consumers didn’t consume these products, so the evolution is very important. The organic market accounted for €5 billion sales in 2014, or 2.5% of the total French food market. But the market share of traditional specialist organic retailers fell from 40% in 2007 to 36% in 2011, while that of mass-market retail rose to 47% of total sales.

Figure 1. Presentation of French Food Retailers.

The remainder of the market consists of direct sales (markets, AMAP, and producers). Local provision has developed through alternative routes, better known as “short food circuits.” These offer an alternative to the dominant model of industrialized and standardized agriculture symbolized by mass distribution (Beaudouin & Robert-Demontrond, 2016). The distribution method of short circuits (local system) does not in itself constitute a new system, since it was dominant for centuries, up until the emergence of mass distribution. Yet this system, which had almost disappeared, has experienced a real renaissance marked by a renewal of its methods (Dufeu & Ferrandi, 2013); its economic importance has grown exponentially. According to the agricultural census of 2011,3 21%, or more than one out of every five farmers, sell their products through these short circuits, or local routes. Among the new forms of local short circuits, the Association pour le Maintien d’une Agriculture Paysanne (AMAP), based on a local fair trade approach, is attracting an increasing number of farmers.

In the following parts, we will focus on integrated and independent retailers because they represent more than 80% of the market share.

A Discourse Analysis of Integrated Retailers’ Sustainable Reports (Lavorata, Morin-Delerm, & Pierre, 2009)

Our first study was carried out in 2005. This enables us to compare with current practices. We studied the sustainable development reports (for the 2005 financial year) of three French distributors (Carrefour, Casino, and Auchan). The introduction to the 2005 sustainable development reports, drafted by the managements of Auchan, Carrefour, and Casino, emphasized the policy of integrating sustainable development in the management of these organizations. For example, P. Baroukh and A. Mulliez, the top executives at Auchan, stated in 2005: “We are aware of the various expectations of all our stakeholders that we should be actively involved in the birth of sustainable economic and social development. It is our sincere concern to work on this.” J.-L. Duran and L. Vandevelde, the top managers of Carrefour at that time, made the following statement: “Sustainable development is increasingly impacting our strategies, working methods, and product design. It should not be considered a constraint, but should become a component in our marketing approach and product offering.” They also said: “2005 marked a turning point in the group’s strategy with a return to growth. To maintain growth in the long term, it must be accompanied by the recognition of all our economic, social and environmental responsibilities, making people the focal point of our strategy.” Finally, J.-V. Naouri, CEO of Casino, claimed: “We are more than ever convinced that economic development, social responsibility, and environmentally-friendly operations can go hand-in-hand and are pursuing our efforts to ensure constant improvement of our performance on these three aspects of sustainable development.” The general theme is that CSR promises the harmonious coexistence of business imperatives and social responsibility.

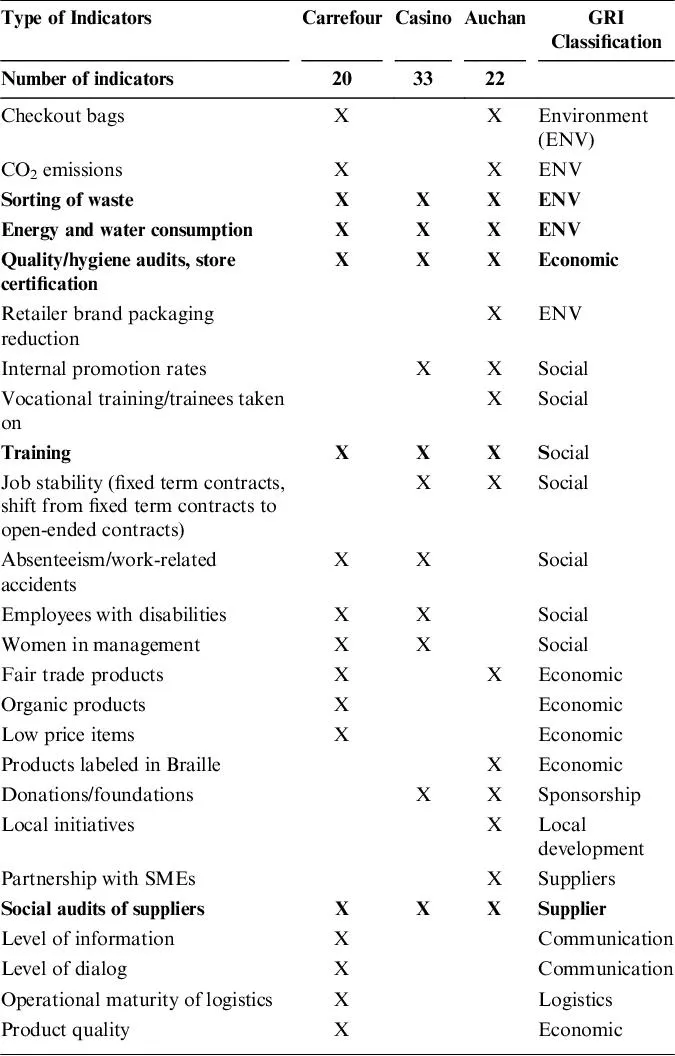

In all these reports, the retailers present indicators that are used to assess the progress made in comparison with the previous year’s report, some of which are inspired by the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). The term Triple Bottom Line distinguishes three aspects of sustainable development – economic (“profit”), social (“people”), and environmental (“planet”); many companies use it in their sustainable development reports and press releases (Shell, Dow Chemicals, Carrefour, Auchan, etc.). According to the Triple Bottom Line terminology, a number of indicators are provided around the three pillars of sustainable development: economic (products, etc.), social (professional training, male-female parity, etc.), and environmental (reduction of packaging, reduction of CO2 emissions, etc.). Organizations such as the GRI promote this tool, which provides “a sustainable development reporting reference system that is as credible as financial reporting, that is, founded on principles of comparability, rigor and verifiability” (Aggeri, Pezet, Abrassart, & Acquier, 2005). Created in 1997 by CERES, the GRI offers a set of social, environmental, and societal indicators on which companies are required to report. Accordingly, we set out to establish which indicators were present in the sustainable development reports of various French retail chains. While the GRI centrally provides sustainable development representation standards that are laid down for companies, we can still ask to what extent these are used by retailers. We looked at each indicator and compared them by retailer (see Table 4).

Table 4. Sustainable Development Indicators Used by the Three Retailers.

Only five indicators (in bold in the table) are used by the three retailers: apart from the indicators that are mandatory under the French New Economic Regulations law, the retailers choose their own evaluation criteria. On the other hand, it seems that although the three dimensions of sustainable development (economic, social, and environmental) appear among these indicators, there is a difference: the social dimension is given more weight than the environmental and economic dimensions. Moreover, other indicators occur (such as the extent of communication with shareholders or social audits of suppliers) that are not easily classifiable within these categories. Furthermore, these GRI indicators are to a large extent used as window dressing. Companies select those on which they intend reporting, for it is certainly easier for them to cut back on waste or CO2 emissions since such reductions also enable them to make savings. On the other hand, it is probably more difficult and costly for them to set up genuine partnerships with their suppliers. As a consequence, some researchers would like to see the GRI indicators become mandatory and the information provided by the retailers to be certified by an independent body, so as to create a real sustainable development policy (Aggeri et al., 2005). In addition, although sustainable development reports are in principle addressed to all stakeholders, it seems unlikely that consumers are aware of this predominantly corporate means of communication. The main targets of these reports are shareholders and institutional actors rather than consumers.

French distributors – whose sustainable development departments are still very modest in size – devoted most of their energy to communication activities. Within each company, they raise the awareness of the Business Units and functional departments of their social responsibility/sustainable development approach by encouraging them to take (often symbolic) actions, on issues that have been relatively poorly analyzed. However, their work consists mainly of organizing and coordinating feedback in order to identify “best practices” and collect data on the indicators that will enable them to demonstrate that progress has been achieved. These indicators are generally selected following extensive benchmarking, followed up by a team appointed to choose those that are most relevant for the business and add a few more. All or some of the information collected is then used to prepare ...