![]()

Appendix 1: Key Players

Clement Attlee

(3 January 1883–8 October 1967)

Remembered as a decent and modest man, Clement Attlee also led what was arguably Britain’s most radical government ever. Yet he had served his apprenticeship as Deputy Prime Minister to one of the most famous Conservatives of all time, Winston Churchill. During the coalition which was to govern Britain for most of the Second World War, Attlee proved a loyal and able number two. In June 1940, with Britain’s army thrown back across the Channel, Winston Churchill faced a Cabinet vote concerning peace negotiations. Churchill wanted to fight on; some in his own party disagreed. It was only with Attlee’s vote that Churchill was able to cling on.

Circumstance placed the two party leaders together. The Labour Party under Attlee had opposed Chamberlain’s appeasement policy and insisted on his resignation after the Norway debate. Attlee himself had only secured the leadership in 1935, when his predecessor George Lansbury had resigned over sanctions against fascist Italy. Until 1945, Attlee would distinguish himself as Churchill’s loyal deputy, regardless of party. As Deputy Prime Minister, he was effectively entrusted with all domestic issues – and Churchill had left them in good hands.

Attlee was a barrister from London and a teacher at the London School of Economics. He had a happy and stable marriage, with four children. Influenced by socialist writers such as Ruskin, he had joined the Independent Labour Party in 1908. He saw extensive active service during the First World War, ending the conflict as a Major, but having been seriously wounded.

After serving in local government, he was elected to Parliament in 1922. He worked as Ramsay MacDonald’s Parliamentary Private Secretary and was rewarded in 1929, when he became Postmaster General in the first Labour government. When MacDonald split the party to form a National government in 1931, Attlee stayed with Labour and became deputy to the new leader, Lansbury. As leader from 1935, he was forthright on the need to support Republican Spain and to challenge Fascism.

When the Second World War came to a close, Attlee’s party colleagues put him under pressure to insist on an early election. Loyal to Churchill, he was reluctant to do so. Once the decision was taken, however, he chose to author the party manifesto – one of the boldest in British history. Securing a landslide, Attlee’s 1945 government would introduce the National Health Service, nationalize the railways, Bank of England, coal mines and other industries, and begin decolonization with India. By the election of 1950 he was tired, and barely scraped back into office. In 1951 he lost to Churchill.

Arguably, Attlee should have retired then. He stayed on as Leader of the Opposition and lost the succeeding election to Anthony Eden. Retiring within eight months of Churchill, Attlee was given a peerage and served in the House of Lords until his death. As a parliamentarian, Attlee was known for his integrity, efficiency and brevity.

In January 1965, Attlee stood in freezing conditions for several hours in order to see Churchill’s funeral cortège. Less than three years later, his own funeral would be a more humble occasion; but for many, his achievments in office were tribute enough.

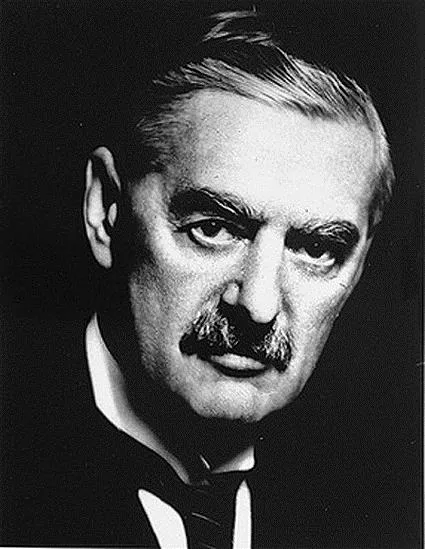

Neville Chamberlain

(18 March 1869–9 November 1940)

What became known as Britain’s ‘appeasement’ policy will be forever associated with Neville Chamberlain; however, his political record is actually a more mixed one. His relationship with Winston Churchill, too, was more nuanced than is generally reported. For Churchill had once been an ally, supporting Chamberlain when he replaced Stanley Baldwin as Prime Minister in 1937.

Chamberlain’s policy on Europe – particularly Germany – was to drive the two men apart. The genesis of appeasement lay in Britain’s attitude to the Spanish Civil War, coloured by Conservative hostility towards Communism. As Prime Minister, Chamberlain tended to dominate foreign affairs, at the expense of Eden, his Foreign Secretary. He insisted on strict neutrality with respect to the war in Spain and was instrumental in pushing France in the same direction. As that war drew to a close, Churchill saw the need to support the Republicans (despite their Communist backers) as a means of preventing a German–Spanish alliance. Along with Eden, he opposed the ensuing Munich Agreement.

Chamberlain’s motives were the genuine belief that appeasement would prevent another European war, coupled with a sense that Germany had been harshly treated at the end of First World War. There was actually some merit in both arguments. When the Germans seized the whole of Czechoslovakia and then Poland, although Chamberlain did not hesitate to declare war on Germany, he had little credibility in Parliament. Yet he stayed on as leader of his party and a member of Churchill’s national coalition, until ill health forced his retirement. During this brief period, he was to work hard to secure Conservative support for the new government.

Chamberlain came from a wealthy political family with plantations in the Bahamas. His father and brother were both prominent politicians. He spent his early career farming in the Bahamas, before working in the metal industry in Birmingham. Moving into politics, he became Mayor of Birmingham and then MP for Ladywood. Chamberlain’s central political views were philanthropic, drawing on his Unitarian religious background. He believed in improving the lot of the poor, sharing this outlook with Churchill. His record as Chancellor of the Exchequer under MacDonald underlines this, with the abolition of the Poor Law and interventionist industrial policies. He was a formidable minister, highly regarded on all sides. Yet with appeasement, he was to lose the respect of the Liberal and Labour parties.

Chamberlain died a bitter man. Lambasted by the press and in such publications as Guilty Men, he could not shake off his reputation for weakness. By 1940 he was already terminally ill with cancer, although his doctors kept this from him. Churchill delivered a tribute at the funeral in Westminster Abbey.

Clementine Churchill

(1 April 1885–12 December 1977)

Born Clementine Hozier, the woman who was to become Winston Churchill’s wife came from straitened circumstances. Her parents separated when she was young, and she grew up in Britain and France, her mother unable to afford the university education recommended by her teachers. Like Churchill, she had aristocratic blood, though it seems possible that she was illegitimate.

They first met when she was 19, and Churchill a 29-year-old MP, noted for his radical views and wartime adventures. The occasion was a dance, at which the rather gauche Churchill failed to impress. Four years later they sat together at a dinner, and matters turned out very differently. Clementine had been engaged several times before, always to older men. The romance with Churchill might now be described as ‘whirlwind’: within a month he had proposed, while taking shelter from a rainstorm in a folly at Blenheim Palace. Even so, the marriage might never have taken place. Clementine was furious when she learnt that Churchill had visited 21-year-old Violet Asquith in Scotland, to tip her off about their engagement. It seemed that there had been some kind of romance between Churchill and Violet. After learning about Churchill’s engagement, Violet became depressed and unstable.

Clementine balanced a keen political intellect with a love of children and family life and a talent for offering her husband the support he needed. She was never frightened to speak (or write) her mind. When Winston was in the trenches during 1916, the political Clementine urged him to stay – it would reflect well on him – while the loving wife craved his return to safety. In 1936 they argued furiously about the abdication, Clementine recognizing that Churchill’s position was hopelessly out of touch with the mood of the nation. She was also totally opposed to another term of office in 1951 – a view which although ignored, was astute and prescient.

As a mother, Clementine was devoted, but at times inflexible. She was to envy her daughter Mary’s warm and relaxed relationship with her own children in years to come. She was also a woman who worried. With Winston, there were always financial concerns, despite his high earnings from writing. Before living at Chartwell they never quite settled either, and she fretted about the move from one house to another. Then there was his drinking and his gambling, and towards the end of his life, his health. Seemingly stoical, all of these challenges took their toll on Clementine.

Clementine Churchill worked hard throughout her life. Modern critics might argue that she sacrificed herself in order to support her husband, though values during her era were different. She ran his household for him, and brought up his children. It was Clementine to whom he would turn when an important dinner party needed to be arranged in a hurry. Later, as the Prime Minister’s wife, she took on significant public duties, with the ‘Mrs Churchill’s Fund’ being the most famous. Yet as far back as the First World War she had been involved in voluntary work.

There are aspects of Clementine Churchill’s personal life which are less well known. In 1918, perhaps worried about the family budget, she secretly discussed the possibility of giving her newborn child to General Sir Ian Hamilton and his wife Jean. Winston was never told about the deal, which came to nothing. Although strong and loyal, she became infatuated with an art dealer during the 1930s; some have alleged an affair, but the balance of historic opinion is that the relationship was platonic.

After her husband’s death, Clementine Churchill became a cross-bench member of the House of Lords. Increasing deafness meant that she was unable to devote as much time to politics as she had hoped – she had always had strong convictions. She enjoyed a quiet retirement, based with her immediate family, succumbing to a sudden heart attack while at home.

Lord Randolph Churchill

(13 February 1849–24 January 1895)

Randolph Churchill exerted a profound influence on his son Winston in a number of ways which he perhaps would not have envisaged. First, their difficult personal relationship, characterized by Randolph’s high expectations and Winston’s initial failure to meet them, clearly left its mark. Second, Randolph’s political career can be summarized as one of unmet potential. This too, coupled with Randolph’s early death, influenced his son. Close to his own death, Winston was to confide to his daughter Mary that his one regret was that his father had not seen him make a success of his life.

Active in the Conservative Party from a young age, Randolph Churchill entered Parliament in 1874, shortly after his marriage. Within a few years he had a reputation as a troublemaker – sharp-tongued, and as critical of his own party as he was the Liberals. He was impatient with what he saw as the elitism and naivety of the Conservatives. Randolph was anxious for change, arguing that the party needed to represent the ordinary members of society or face permanent opposition. Liberal reforms should be considered on merit, rather than rejected out of hand. This series of ideas coalesced into what he termed ‘Tory Democracy’, and initially made him few friends. Arguably, his most important legacy was to shift the party’s centre of gravity in this direction.

For by 1885 he could no longer be ignored. He was brought into government as Secretary of State for India. Within a year he was promoted to Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House – more or less dictating his own political terms. It seemed nothing would stop Randolph Churchill; here was a Prime Minister in the making.

By 1887, however, it was all over. In December 1886 he had overplayed his hand during a budget row with the War Ministry. He resigned, perhaps being surprised when this was actually accepted. Moving to the backbenches, Randolph’s career quickly lost its lustre. He was now beginning to show the symptoms of the illness which would kill him at the age of 45. Sometimes incoherent, his speeches in the House became embarrassing.

Debate continues about Randolph’s illness. For many years it was accepted that he had syphilis; this now seems less likely, with modern weight of opinion favouring a brain tumour. Whatever the cause, Randolph Churchill was a talented man stricken down early.

Although his academic achievements were modest, Randolph had been to Eton and to Oxford University. An attractive and self-confident young man, he married well, and controversially. Jennie Jerome was a noted American beauty from a wealthy background; but not aristocratic enough for some members of his family. He expected great things of his son, and would never know the extent to which his own achievements would be eclipsed by Winston.

Anthony Eden

(12 June 1897–14 January 1977)

When Churchill appointed Anthony Eden to be his Foreign Secretary in 1940, he secured the services of a man who had already done the job for three years. Furthermore, Eden had served an apprenticeship as a junior minister in the Foreign Office prior to that. He was also a man who had the integrity to resign over appeasement in 1938. During the war, Eden served with distinction, but mostly in an advisory capacity, leaving Churchill to conduct face-to-face diplomacy.

After the Conservative defeat of 1945 he worked as Churchill’s deputy. Taking up the foreign brief again in the 1951 government, Eden was easily Britain’s most experienced Foreign Secretary of the twentieth century. Ironic, therefore, that it was a foreign-policy decision which would later end his political career. Though loyal to Churchill during the war, by the 1950s he was anxious for the leadership himself. He made little secret of this and was instrumental in Churchill’s ultimate resignation, as well as in blocking his mission to Moscow following Stalin’s death.

With a landed background from the north of England, an Eton and Oxford education, dashing looks and impeccable tailoring, Eden was every inch the English gentleman. He had served with distinction during the First World War and from there won the Conservative seat of Warwick and Leamington in the 1923 election. By 1926, he was Parliamentary Private Secretary to Austen Chamberlain at the Foreign Office, before being given a junior ministerial position in the same department in MacDonald’s 1931 government. By 1935, when MacDonald appointed him Foreign Secretary, he had worked in the area of foreign affairs for nearly a decade. Before assuming the pr...