This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

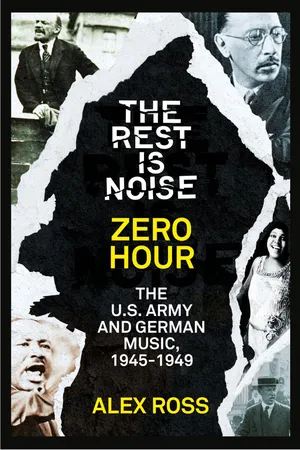

This is a chapter from Alex Ross’s groundbreaking history of twentieth-century classical music, ‘The Rest is Noise’. Further extracts are available as digital shorts, accompanying the London Southbank festival programme.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Rest Is Noise Series: Zero Hour by Alex Ross in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Music10

ZERO HOUR

The U.S. Army and German Music, 1945–1949

On April 30, 1945, the day of Hitler’s suicide, “zero hour” in modern German history, the 103rd Infantry and Tenth Armored divisions of the U.S. Army took possession of the Alpine resort of Garmisch-Partenkirchen, which the war had hardly touched. Two hundred Allied bombers had been poised to lay waste to the town and its environs, but the strike was called off at the behest of a surrendering German officer.

Early in the morning a security detachment turned in to the driveway of a Garmisch villa, intending to use it as a command post. When the senior officer, Lieutenant Milton Weiss, went inside the house, an old man came downstairs to meet him. “I am Richard Strauss,” he said, “the composer of Rosenkavalier and Salome.” Strauss studied the soldier’s face for signs of sympathy. Weiss, who had played piano at Jewish resorts in the Catskills, nodded his head in recognition. Strauss went on to recount his experiences in the war, pointedly mentioning the tribulations of his Jewish relatives. Weiss chose to install his post elsewhere.

At 11:00 a.m. on the same day, a squad of jeeps came up the drive, these led by Major John Kramers, of the 103rd Infantry Division’s military-government branch. Kramers told the family that they had fifteen minutes to evacuate. Strauss walked out to the major’s jeep, holding documents that declared him to be an honorary citizen of Morgantown, West Virginia, together with part of the manuscript of Rosenkavalier. “I am Richard Strauss, the composer,” he said. Kramers’s face lit up; he was a Strauss fan. An “Off Limits” sign was placed on the lawn.

In the days that followed, Strauss posed for photographs, played the Rosenkavalier waltzes on the piano, and smiled bemusedly as soldiers inspected his statue of Beethoven and asked who it was. “If they ask one more time,” he muttered, “I’m telling them it’s Hitler’s father.”

All over Europe, young veterans were emerging from the rubble of the war into adulthood. Among them were several future leaders of the postwar musical scene, and they would be indelibly marked by what they had experienced in adolescence. Karlheinz Stockhausen was the son of a spiritually tortured Nazi Party member who went to the eastern front and never returned. His mother was confined for many years to a sanatorium, then killed in the Nazi euthanasia program. By the age of sixteen, Stockhausen was working in a mobile hospital behind the western front, where he tried to revive soldiers who had fallen victim to Allied incendiary bombs. “I would try to find an opening in the mouth area for a straw,” he recalled, “in order to pour some liquid into these men, whose bodies were still moving, but there was only a yellow ball-like mass where the face should have been.” On a given day Stockhausen and his comrades would haul thirty or forty corpses into churches that had been converted into morgues.

Hans Werner Henze trained as a radio operator for Panzer battalions and spent the first part of 1945 riding aimlessly around the ruined landscape. Bernd Alois Zimmermann was drafted at the age of twenty-one and served in Poland, France, and Russia. Luciano Berio was conscripted into the army of Mussolini’s Republic of Salò and nearly blew off his right hand with a gun that he did not know how to use. Iannis Xenakis joined the Greek Communist resistance, fighting not only the Germans but also the British, who, in an early demonstration of Cold War Realpolitik, made common cause with local Fascists when they occupied the country. At the end of 1944 a British shell landed on a building where Xenakis was hiding; after watching a comrade’s brains splatter against a wall, he passed out and awoke to find that his left eye and part of his face were gone.

In July 1945, the young English composer Benjamin Britten, who had just scored a triumph in London with his opera Peter Grimes, accompanied the violinist Yehudi Menuhin on a brief tour of defeated Germany. The two men visited the concentration camp at Bergen-Belsen and performed for a crowd of former inmates. Stupefied by what he saw, Britten decided to write a cycle of songs on the Holy Sonnets of John Donne, the most spiritually scouring poetry he could find. On August 6 he set to music Sonnet 14, which begins, “Batter my heart, three person’d God.” Earlier the same day, the fi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Zero Hour

- Notes

- Suggested Listening and Reading

- Copyright

- About the Publisher