I

Introduction: Rehabilitating the Borderline

Kama da wane ba wane ba ne.

Similarity is not the same thing as identity.

—Hausa proverb

Incongruously, provocatively, it towers on high: a fifteen-foot metal pole, springing out of the dirty brown Sahelian sand. No other human artifact is to be seen in this vast, barren, flat savanna; only an occasional bush, a tenacious shrub, a spindly tree break up the monotonous, infinite landscape. One stares and wonders how, by beast and porter, such a huge totem could have been lugged here and erected in this desolate bush. But there it stands: a marker of an international boundary, a monument to the splitting of a people, a symbol of colonialism, an idol of “national sovereignty.” Local people refer to it as tangaraho.

“Tangaraho” literally means “telegraph pole.” Between 1906 and 1908, sixty-three of these thick metal rods were placed on or near the thirteenth and fourteenth northern parallels, between the fourth and the fourteenth eastern longitudinal marks in West Africa. The exact placement of these poles had been determined far away, in London, by British and French diplomats who had never set foot in the territory. Nor would they ever visit here. Yet for the people who live in the areas where the poles were erected the consequences have been far-reaching.

The poles would determine the identity, fate, and life possibilities of the people along and behind them. First under European colonial rule and then under independent African governments the tangaraho has come to identify the spot where one alien power ends and the next one begins.

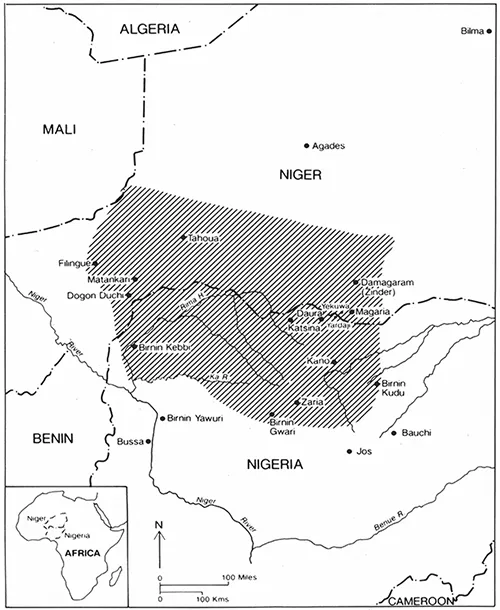

The tangaraho symbolizes what the local inhabitants call yanken ƙasa. The noun “ƙasa” means country or homeland; “yanke,” a verb, means to split, to cut, to rip, as with a knife. “Yanken ƙasa” may thus be rendered “the splitting of the country.” The country is called Hausaland, but don’t look for it on any map of the world. Hausaland may exist for the Hausas and for their ethnographic and historical chroniclers (Map 1), but as a political entity it ceased to exist shortly after the turn of the century.

To stand on one side of the pole is to be, in common parlance, in Faranshi (France); to step across it is to enter Inglishi or, more commonly, Nijeriya. For the people who live here, these designations have not changed for well over eighty years. Westerners and “educated” Africans, though, distinguish thus: from 1890 to 1960, the territory was divided into two colonies, under British and French rule. One is remembered as the Colonie du Niger, which was part of Afrique Occidentale Française (AOF), or French West Africa. The other was the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria. After 1960, the former became the République du Niger; the latter is now the Federal Republic of Nigeria (see Map 2). Around the tangaraho, people also know they are either ’yan Nijeriya or ’yan Faranshi—that is, people of Nigeria or people of Niger. But though they are split into two sovereign states, they still live in Hausaland. They are still Hausa.

Does it matter on which side of the tangaraho the Hausa people live, here in the remote, outer fringes of Niger and Nigeria? Do those heady global phenomena of “European colonialism” and “Third World national liberation” actually make a difference in the lives of humble Hausa peasants, eking out survival from the sandy Sahelian soil? These are the immediate questions that this book aims to explore. An overarching consideration is the contribution of “borderline” studies for inquiries into nation building, national consciousness, and ethnic identity, particularly in an era when so many states are unstable.

Map 2. Niger and Nigeria in Africa

Comparative Borderline Studies

A revealing, if unfortunate, meaning of the term “borderline” is marginal: not important, nonessential, dispensable, not quite standard. Social scientists, no less than government officials, have generally dismissed borderland communities as “borderline” in this pejorative sense and thus peripheral to mainstream concerns. Yet an immense amount can be learned if we pay greater attention to the interstices of states, particularly when they bisect members of a single ethnic group.

The partition of colonial Africa provides a textbook case of ethnic divisions along seemingly artificial boundaries. But ethnic partition is not unique to Africa. Indeed, Europe is replete with such cases. Two particularly compelling borderlands that have commanded the attention of scholars are the Basque country and Catalonia, both spanning the boundaries of France and Spain.

Thomas Lancaster’s (1987) survey research reveals that, despite a higher degree of ethnic consciousness among the Basques of Spain than among those of France, in general both groups accept the legitimacy of state sovereignty and their own identification as French and Spanish citizens. These findings parallel to a remarkable extent the situation that prevails along the Nigeria-Niger boundary with respect to the Hausa.

Peter Sahlins’s (1989) examination of the Cerdanya Valley, which straddles France and Spain in the Pyrenees (Catalonia), is more historical in approach and more comprehensive in scope. Yet Sahlins’s conclusions replicate Lancaster’s and foreshadow developments in Hausaland. “Frontier regions are privileged sites for the articulation of national distinctions,” Sahlins writes. “In many ways the sense of difference is strongest where some historical sense of cooperation and relatedness remains” (271). A particularly interesting observation, and one that anticipates challenges to European-African borderland comparability, is that this sense of intraethnic cross-border differentiation antedated material development and differentiation along the frontier. Long before French Cerdagne began to enjoy an infrastructure superior to Spanish Cerdaña’s (a development that Sahlins places in the 1880s, coincidentally when the European division of Hausaland was just beginning), an unmistakable sense of national (in contrast to ethnic) identity had developed. “Cerdans came to identify themselves as French or Spanish, localizing a national difference and nationalizing local ones, long before such differences were imposed from above” (286).

Can the experiences of the Catalan and Basque borderlands be regarded as prototypes for an analysis of the division of Hausaland? If so, these histories can indeed help us to understand the partitioned borderland phenomenon today, in Africa as well as Europe. They would also shed light on the processes by which partitioned border communities deal with externally introduced levels of identity and the development of national consciousness in new states.

Or does the prototype paradigm undermine the singularity of the African experience? Do the conquest, partition, and colonization of Africans by Europeans not irremediably qualify the comparison? Despite the “parallels between the means French rulers employed to gain the loyalty of a subject population abroad and the cultural apparatus of induced loyalty at home,” observes Herman Lebovics (1992:132), “we should not automatically assume that the growth of Parisian power in the provinces should be understood as the same process as the ascendancy of France over distant colonies” (126). Indeed, such assumptions must be subjected to analysis, particularly comparative analysis.

Assimilation and the Colonial Enterprise

To be sure, the racial dimension to colony building in Africa cannot be dismissed. There prevailed throughout the colonial enterprise a general belief in the superiority of lighter over darker peoples. Moreover, the implantation of an intermediate level of government (the local colonial administration) between the metropolitan sovereign and the overseas population complicated the relationship between indigenous communities and “national” society: a dual allegiance, to the colonial capital and to the “mother country,” was imposed.

But aside from these qualifications, how novel actually was the enterprise of European hegemony building? The colonization of Africa represented the extension of a process that characterized nation building in Europe. The strategy of assimilation—of incorporating the colonized into the colonizer—developed in Europe for Europeans. Indeed, as Eugen Weber brilliantly documents in Peasants into Frenchmen (1976), France became France in the first place through an internal process of assimilation that was “akin to colonization” (486). For Weber, not until World War I was the peasantry of France transformed into truly French peasants. “[U]ncivilized, that is unintegrated into, unassimilated to French civilization: poor, backward, ignorant, savage, barbarous, wild, living like beasts with their beasts” (Weber 1976:5): these were terms employed by Gallic Frenchmen not to denigrate colonials of color but to designate racially similar but no less disdained countryfolk. It is all the more striking that such attitudes prevailed during an era when France was colonizing overseas. Or perhaps one should say, when France was colonizing also overseas.

For colonization and its attendant rationalizations persisted in the metropole as well. Landes, certainly no hinterland outpost, came in for particular approbation. Populated by a “people alien to civilization,” it was often compared to a cultural and physical desert: “our African Sahara: a desert where the Gallic cock could only sharpen his spurs.” But Landes was by no means alone: well into the twentieth century, parts of Arcachon were likened to “some African land, a gathering of huts grouped in the shadow of the Republic’s flag.” Or Sologne: “clearly a question of colonization.” Brittany complained of state efforts in “faraway lands [i.e., Africa] to cultivate the desert [when] the desert is here.” Limousin bitterly noted that “they are building railway lines in Africa” and demanded comparable treatment. Perhaps more illustrative of the colonial parallel was the argument for use of the same French-language teaching method employed in Brittany (i.e., target language immersion) in Africa. The proposal was defended “as applicable to little Flemings, little Basques, little Bretons, as to little Arabs and little Berbers” (contemporary sources quoted in Weber 1976:488–90).

Long after Gallic assimilation had proceeded to create more epigrammatic “black Frenchmen” throughout the empire (see Murch 1971), metropolitan assimilation was still laboring to create white Frenchmen. Though the process was certainly more pronounced in France than in Great Britain, even there the task of turning English, Scots, and Welsh into people with a British identity entailed a recognizable strategy of cultural assimilation. (The mitigated success of British assimilation in Northern Ireland, another example of metropolitan colonialism, helps explain the persistence of severe conflict there.) As Linda Colley (1992) demonstrates, however, the underpinnings of “Britishness” are external and transient, casting doubts on the solidity of British national identity.

Religion, warfare, and colonization are the three factors that combined to “invent Britain,” says Colley. But now that Britain can no longer boast about defending Protestantism, no longer needs to defend itself against France, and no longer reigns over an august (and profitable) overseas empire, it is not only less Great but less British. Defining Britain as “an invented nation superimposed, if only for a while, onto much older alignments and loyalties” (1992:5), Colley traces the process by which three culturally and politically distinct peoples, the English, Welsh, and Scots, were amalgamated into one.

Overseas colonization, with its assimilationist subtext, was not sui generis. It was the continuation of a core imperialism—sometimes brutal, sometimes subtle—that originated in and was originally applied within the metropole itself.

Both Weber and Colley describe “modern” (i.e., eighteenth- and nineteenth-century) processes of nation building that evoke familiar variations in assimilationist strategy. Early metropolitan imperialism in Europe, however, belies the oft-invoked dichotomy between Gallic and Anglo-Saxon colonization policies. James Given (1990) finds that in the thirteenth century greater local autonomy was retained (and tolerated) in an area of French domination (Languedoc) than in English-conquered Wales. Given’s medieval comparison serves as wise caution regarding the transience of so-called core elements of culture as well as the historical limitations of our own time-bound theories.

Herman Lebovics’s (1992) historical inquiry into the battle over French cultural identity in the first half of the twentieth century also tempers the image of a unidirectional French assimilationist project. As his ironically titled chapter on the French colonial enterprise in Vietnam (“Frenchmen into Peasants”) elucidates, there have been even recent contexts and circumstances in which “assimilation” could be promoted by a return to the native language, arts, history—but always in ways conceptualized and molded by (so as to buttress the overall interests of) the colonizer. Lebovics is skeptical that any wall (high or otherwise) categorically separated assimilation from association (a more tolerant colonial cultural policy that ostensibly allowed for the coexistence of indigenous norms along with French sovereignty). Lebovics’s skepticism is justified: French colonial association never approached the degree of cultural, not to mention political, autonomy of modern British rule.

Borderlands, National Integration, and Decolonization

Revolution, secession, and fragmentation in Eastern Europe, Czechoslovakia, and the former Soviet Union in the last decade of the twentieth century should remind us that even the mightiest of empires can be brittle constructs. Such developments should also serve as reminders that national integration of plural societies is far from irreversible—a point that Colley can make only prophetically for her fellow Britons. The end of the experiment in communist and Soviet-style nationalism provides stronger evidence that assimilation needs to be rooted in a core culture that is both relevant and functional: ideology alone does not provide the necessary glue.

Of course, one could claim that it was the material failure of Soviet communism that doomed Soviet nationalism, not the insufficient ideological basis of its assimilating mission. Yet analyses of nationalities immediately ...