![]()

1 Introduction

An overview of the international trading system

Introduction

International trade did exist since time immemorial, but it may safely be argued that it had never been more liberalized, less discriminatory, and more globalized than it is today. If history is any guide, even up until the eighteenth century international trade regimes were driven by imperial, colonial, and mercantilist forces. Moreover, such trade regimes, by and large, were coercive, restrictive, and discriminatory in character, and, more often than not, driven by beggar-thyneighbor policies. It was in the nineteenth century that the world began to witness a discernible move toward bilateral trade treaties that embraced greater openness and liberalization (WTO, 2011, 48–51). Such moves were, however, either halted or reversed by the powerful protectionist developments in the 1870s and during the interregnum between the two World Wars. It is only since World War II that the world has been witnessing a sustained development toward a more liberalized international trading system, which incessantly propels greater integration and interdependence of economies and nations around the world.

Much of the credit for the thrust for such a powerful and far-reaching development may be attributed to the Bretton Woods Conference of 1944,1 in which the victorious world leaders envisaged a new world economic order with three key pillars: the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which would provide global exchange rate stability, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (the World Bank), which would provide reconstruction capital for war-ravaged countries, and the International Trade Organization (ITO), which would oversee the administration of a more liberalized multilateral trading order. While the first two of the proposed institutions of the new global governance structure came into being, the ITO could not be realized—thanks to vigorous opposition from US Congress.2

With the collapse of the ITO initiative, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) emerged as a temporary platform for governing international trade. The origin of the GATT may be traced to the ongoing deliberations among the US and some of its allies since 1945 to boost international trade by reversing the devastating legacy of protectionist measures of the 1930s (Hoekman, 2002; Eichengreen and Irwin, 2010). These countries signed the original GATT agreement on October 30, 1947 in Geneva, with the objectives of raising living standards across the world by ensuring full utilization of global resources, increasing volumes of real income and effective demand, and expanding the production and exchange of goods and services under a more liberalized trade regime (GATT, 1972).3

The GATT was founded on the twin principles of reciprocity and non-discrimination. While the principle of reciprocity envisaged mutually advantageous arrangements among contracting parties for reciprocal reductions in tariff bindings, the principle of non-discrimination envisaged uniform rights and obligations of all contracting parties. In operational terms, the latter meant the Most-Favored Nation (MFN) treatment of all contracting parties of GATT; in other words, multilateralization of reciprocal tariff reductions that contracting parties might negotiate bilaterally (Bagwell and Staiger, 2004, 54–58). Although 11 of the 23 signatories were developing countries, the original GATT agreement contained no special provision for them.4 The temporary GATT, thus established to reduce trade barriers through bilateral agreements, survived for almost five decades, before it was absorbed into the World Trade Organization in 1995.

Multilateral negotiations under the GATT

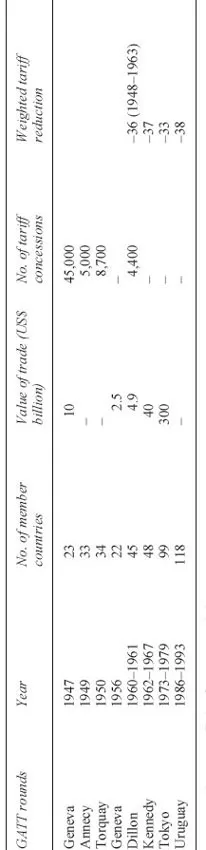

Over the course of its existence, the GATT (1947–1994) provided a global platform for rule-based trade regimes, settled scores of international trade disputes, and achieved a total of eight rounds of multilateral trade negotiations (see Table 1.1). The first GATT round established the GATT itself—it guaranteed MFN status to all contracting parties on a reciprocal basis and agreed on concessions to some 45,000 tariff lines worth $10 billion, one-fifth of global trade at that time. In all, the first five GATT rounds of trade negotiations between 1948 and 1963 succeeded in reducing weighted tariffs by 36 percent. The next three rounds—the Kennedy Round (1964–1967), the Tokyo Round (1973–1979), and the Uruguay Round (1986–1994) brought down tariffs further by another 37 percent, 33 percent, and 38 percent, respectively.

The GATT rounds of trade negotiations also addressed non-tariff barriers (NTBs). The Kennedy Round, for example, hammered out agreements on customs valuation and anti-dumping issues, and the Tokyo Round further widened the GATT coverage on NTBs by reaching agreements on subsidies and countervailing measures, technical barriers to trade (TBT), import licensing procedures, anti-dumping laws, and government procurement. Another lasting contribution of the Tokyo Round was the ‘Enabling Clause,’ which allowed GATT contracting parties to grant favorable tariff and non-tariff treatments to the developing countries under what came to be known as the Special and Differential Treatment (SDT) measures. With each round of trade negotiations, up until the Uruguay Round, the GATT contributed to the further liberalization of the international trading system, but many countries still continued to use bilateral agreements to impose voluntary export restraints (VERs), quota restrictions (QRS), and other such trade-distorting measures.

Table 1.1 The GATT negotiating rounds, 1947 to 1994, and major achievements

Source: Author’s compilation from WTO website.

GATT discrimination against the exports interests of developing countries

Multilateral trade negotiations of the first seven rounds of the GATT, prior to the Uruguay Round (1986–1994), however, concentrated primarily on the reduction of tariffs and NTBs to manufactures only. Moreover, these negotiations were participated in mainly by industrialized developed countries. Although some developing countries took part in these negotiations, they merely served as onlookers—since only a few of them were manufacturing exporters. Many developing countries were not even members of the GATT at that time—37 of them joined GATT in 1987, following the launch of the Uruguay Round. Moreover, most of the developing countries, prior to the Uruguay Round, swam against trade liberalization—being early in the industrialization process, they were more interested in seeking legitimacies for sheltering domestic production under import substitution, infant industry protection, and such other protectionist agendas.5

Second, up until the Kennedy Round, all tariff negotiations were bilateral—they were based on reciprocal, product-by-product exchange of concessions of manufactures. Developing countries, being primarily agricultural commodity exporters, had little to gain from such negotiations or concessions. The Kennedy Round, for example, brought down tariffs by 50 percent for manufacturing goods, but that affected 26 percent of goods of exports interest to developing countries, compared to 36 percent of goods of exports interest to industrialized countries. Similarly, the Tokyo Round’s tariff reductions affected 26 percent of goods of export interests to developing countries, compared with 33 percent for the developed countries (Hudec, 1987).

Third, while most of the manufacturing tariffs, in which developed countries had exports interests, crumbled with successive rounds of GATT negotiations, tariffs and NTBs to trade in textiles and clothing (T&C), a manufacturing sector in which developing countries had exports interests, moved in the opposite direction. The GATT Agreement left the T&C out of its jurisdiction by designating it as a ‘special case,’6 apparently with the consideration that developing countries, being principally primary good producers, would be unable to reciprocate in manufacturing trade. As explained in Chapter 3, the underlying motivation for designating the T&C as a ‘special case’ actually lay with the implications of ‘low-cost’ imports from less developed countries for employment and economic growth in developed countries. The MFN principle also did not bode well for many developed countries: many chose not to comply with this principle, considering injurious effects of T&C imports on their domestic industries. As a result, and as explained in Chapter 3, highly discriminatory and restrictive trade regimes proliferated in the T&C sector throughout the GATT period, seriously impeding industrialization and economic growth of less developed countries for several decades.

Fourth, agriculture, another area in which developing countries enjoyed competitive advantage, remained almost completely outside the rule-based multilateral trading system throughout the GATT period. As explained in Chapter 2, in the absence of any trade discipline, developed countries faced no difficulty in adopting widespread protectionist measures to insulate domestic agriculture from international competition. A wide variety of instruments were used for such protections, which included market price supports—under which farmers were paid the difference between domestic and international prices; direct supports—under which governments provided product-specific subsidies to domestic producers or consumers; and general agricultural supports—under which governments provided support for agricultural research, training, marketing, and infrastructure. Some developed counties even acquired a competitive advantage in agriculture through massive domestic supports, and exported such subsidized products by depressing international prices. In the absence of any restraints, such protective and trade-distortive measures in agriculture went unchecked for several decades, reaching a peak in the late 1980s.

The Uruguay Round as a watershed event in the multilateral trading system

The Uruguay Round, the final round of multilateral trade negotiations under the GATT, came as a watershed event in the entire history of the global governance of multilateral trade. The seven-year-long negotiations of the Round came to an end in 1994 with the Marrakesh Ministerial Declaration which replaced the GATT itself with a new multilateral trading watchdog called the World Trade Organization (WTO).7 The WTO Agreement, ‘The Final Act Embodying the Results of the Uruguay Round,’ brought all trading sectors—agriculture, manufacturing, and services—under the strengthened multilateral trade rules and disciplines of GATT. In scope and magnitude, it far exceeded that of the botched ITO proposal envisaged by the Havana Charter in 1947, and the provisional GATT agreement it replaced. The WTO Agreement incorporated over a dozen agreements in the goods area, in addition to scores of agreements in services, investment, and intellectual property areas, including the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), the Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs), the Trade-Related Investment Measures (TRIMs), and the Dispute Settlement Understanding (DSU).8

Coming in the immediate aftermath of the Cold War, the WTO Agreement symbolized the universal triumph of capitalism—as a knock-out victory of free market and free trade over autarchic, nationalistic, or protectionist policies of the past. It also came at a point when scores of developing countries developed greater stakes in global manufacturing trade. Several developing countries, especially the East Asian Tigers, graduated from primary commodities to export-oriented manufactures, and some developing countries, such as Bangladesh, China, Malaysia, Mexico, and Turkey, broke into labor-intensive manufactures. A vibrant, rule-based multilateral trading system thus became more relevant to their exports interests than ever before.

The WTO emerged as a powerful watchdog of multilateral trade

Compared with its predecessor, the WTO also came with a much stronger institutional framework for the monitoring and enforcement of multilateral agreements. While the GATT was a provisional intergovernmental treaty in which signatories were ‘contracting parties,’ in the WTO the signatories are ‘members’ who have empowered the WTO to serve as a “regulator of regulatory actions taken by governments that affect trade and the conditions of competition facing imported products on domestic markets” (Hoekman and Kostecki 2001, 37).9 Unlike the GATT, as Higgott and Weber (2005, 434–455) point out, the WTO advances and consolidates commercial law (lex mercantoria), which defines global governance increasingly in terms of the logic of market access. Under this evolving framework, the WTO aims at achieving the progressive commercialization of many public services, which were previously subject to regulation premised on the notion of the public goods provision to all.10 Moreover, unlike the Breton Woods institutions such as the World Bank and the IMF, in which voting rights of members depend on their financial contributions to these institutions, the WTO Agreement grants equal voting rights to all members,11 and, due to what is called the ‘single undertaking’ approach, the WTO’s decisions are equally binding for all its members.

The new architecture of the global trading system, as envisaged by the WTO, also provides stronger frameworks for the negotiation and implementation of multinational trade agreements, the settlement of international trade disputes, the monitoring of trade policies of member countries, and cooperation with sister organizations, such as the World Bank and the IMF, for greater coherence in global economic policy making. Moreover, unlike its predecessor the GATT, which was under no obligation to hold annual meetings, the WTO is officially responsible for holding a biannual meeting of its top decision-making body, known as the WTO Ministerial. The WTO agreements also commit the institution to greater transparency and accountability in all its deliberations and negotiations. On top of all that, all decisions of the WTO must be reached through a consensus.12

The Uruguay Round integrated the textiles and clothing sector into the GATT discipline

The Uruguay Round Agreements also succeeded in sounding a...