This is a test

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hong Kong as an International Financial Centre

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Based on previously unpublished archival records, this book studies the origins of Hong Kong's post war rise to global prominence. It explores the expansion of the gold market, stock market, banking system, foreign exchange market, and insurance in the years 1945-1965. This book makes a significant contribution to our understanding of the developme

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Hong Kong as an International Financial Centre by Dr Catherine Schenk in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Betriebswirtschaft & Business allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Hong Kong in the international economy

Hong Kong has occupied a unique position in the international economy since its initial occupation by British traders in 1842. As a haven for Western traders engaged in commerce with China, the colony of Hong Kong developed into the most important entrepot in East Asia. By the end of the nineteenth century, the island’s reputation as an outpost of colonial influence and free market opportunities attracted thousands of European and Chinese merchants to the colony.1 In the first half of the twentieth century, however, these merchants began to feel the impact that international politics would have on the colony over the next century. The Sino- Japanese War, the Japanese occupation of China and then of Hong Kong from 1941 halted the colony’s development for close to a decade. After the surrender of the Japanese in August 1945, Hong Kong was poised to resume its traditional role as the hub of the Asian economy. However, the economic environment into which Asia emerged in 1945 was changed irrevocably, and the subsequent shifts in the global economy propelled Hong Kong towards a new role in East Asia.

The importance of Hong Kong as an international trade entrepot in the nineteenth century is widely researched but (with some exceptions) the history of Hong Kong in the international economy then skips from the early twentieth century to the 1970s.2 The financial history of the 1950s and 1960s is usually neglected in favour of the more dynamic and easily documented period from the 1970s. Jao’s classic Banking and Currency in Hong Kong remains the authoritative text, although it deals mainly with the 1960s and 1970s and is now more than 25 years old. Another important contribution is King’s The Hongkong Bank in the Period of Development and Nationalism, 1941–1984. The bulk of this volume deals with the period up to 1962 but it is clearly a history of the bank and not of Hong Kong.3 There are also several early economic histories of Hong Kong which cover the 1950s and 1960s from a contemporary viewpoint, but they lack the access to new data and archival resources.4 Another group of histories discuss Hong Kong as a by-product of studies on China.5

The neglect of financial history contrasts sharply with the increasing interest in Hong Kong as a manufacturing centre. This was fuelled by the frenzy that surrounded the analysis of Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan when these ‘Four Little Dragons’ seemed to offer the world a model for modern development (until the financial crisis of 1997).6 The return of Hong Kong to Chinese control in 1997 also sparked a rush of political histories, partly to feed public curiosity about the historical importance of this moment in British imperial history.7

The historical development of financial centres generally has been relatively underresearched, although the development of international financial centres (IFCs) began to attract academic attention in the 1970s with the publication of Kindleberger’s seminal study.8 New interest no doubt stemmed from the dramatic increase in international financial activity brought on by deregulation and the rise of the Euromarkets in this decade. Since then, there has been considerable interest in the defining characteristics of IFCs as well as their development and rank of importance.9 The defining characteristics include whether the banking business is actually performed in the territory, or if it is merely a tax haven, ‘brass plate’, or ‘paper’ centre. Other important features are whether the centre is a capital importer or a capital exporter, and whether there is a regulatory barrier between domestic and international financial activities. Another set of criteria revolve around the geographical range of activity as well as the range of services offered.

A quick glance at Hong Kong’s international financial services in the period 1945–65 confirms three key characteristics: that the colony was not a ‘brass plate’ centre, that it was a net capital importer, and that there was no regulatory barrier between domestic and international transactions. Hong Kong’s financial institutions served the local region as well as customers in the USA and Europe, and the services offered were mainly banking, foreign exchange and insurance. It is the purpose of this book to focus on the role of Hong Kong in the international monetary and financial system in the first two decades after the war, and in the process to expose a new side of Hong Kong’s post-war economic development.

The rise of Hong Kong as an international financial centre is usually measured from its position in the 1970s. This decade saw an influx of foreign banking interests and the mushrooming of non-banking financial institutions that sought to share in the ‘miracle’ economic growth of the colony. In 1979, China emerged from three decades of relative isolation and attracted the attention of international investors the world over. As a wave of optimism swept through capital markets in anticipation of huge profits that the Chinese market seemed to offer, Hong Kong was ideally prepared to become the primary route for Western capital to enter China. Through the 1980s the investments met with mixed fortunes, but Hong Kong firms themselves became substantial investors as they sought to take advantage of cheaper labour costs across the border. As a consequence, the economic integration of Hong Kong with southeast China intensified and presaged political integration. By 1997, when the political handover was completed, 60 per cent of the total overseas capital raised by China came through Hong Kong.10

The role of Hong Kong as a financial centre since the 1970s has been most vigorously researched by Jao.11 He has convincingly argued that Hong Kong became an important regional financial centre in this decade, and that its presence increased even more in the 1980s. This reflected the open-door policy of China from 1979 as well as the general boom in international financial activity due to globalisation. Between 1980 and 1990, Hong Kong banks’ assets increased from US$38 billion to US$464 billion (from 2 per cent to almost 7 per cent of the world total) by which time Hong Kong ranked fourth in the world, trailing only the UK, USA and Japan. By 1990 Hong Kong was host to 138 licensed foreign banks, compared with 30 in 1965. In terms of the number of foreign banking offices, Hong Kong ranked second only to London with a total of 357 in 1995.12

The boom in financial activities in Hong Kong from the 1980s is impressive indeed but the international financial services of Hong Kong have a much longer history, which has not been adequately explored. It is Jao’s contention that ‘Hong Kong’s rise as a regional financial centre began circa 1969/70 and not earlier’ and he attributes the start of Hong Kong’s establishment to the political rapprochement between the USA and China in 1971.13 In contrast, the present study will argue that in the first two decades after 1945, Hong Kong’s financial sector increased in importance largely because of the colony’s unique position in the Bretton Woods system. The banking crisis of 1965 and the political riots of 1966/7 combined to undermine international confidence, and Hong Kong’s relative position declined. In the 1970s, Singapore significantly increased its presence as an international financial centre through government incentives which included encouraging the Asia dollar market. Nevertheless, the financial expertise that developed in the 1950s and 1960s in Hong Kong formed the basis for the subsequent boom in the 1980s. Banking continued to be the foundation of Hong Kong’s international financial activities through the 1990s.14

Evolution of Hong Kong’s economy 1945–65

Hong Kong has gone through various manifestations in the post-war period. In the 1940s it was a bastion of the empire, and a political as well as economic link to China in revolution. This latter aspect was felt most keenly in the influx of immigrants from China between 1946 and 1950. The increased population put extreme pressure on the resources of the colony, but at the same time created the basis for successful industrialisation.15 Throughout the 1950s, the energies of its new population transformed the economy by creating a substantial labour-intensive manufacturing base alongside the traditional financial and commercial services sector. During the 1960s, the global importance of Hong Kong became more widely recognised as these exports made inroads into the mature markets of Europe and the USA. This generated considerable trade friction between Hong Kong and some of its traditional Western trading partners, but industrialists in Hong Kong showed their famous flexibility and continued to flourish. Hong Kong’s famously changing skyline, which became the potent symbol of prosperity achieved with few natural resources, began to take shape in this period. In the 1970s, the industrial restructuring of Hong Kong included the promotion of financial services, and this sector was given added impetus after the opening of the Chinese economy to the West from 1979.

While this rags-to-riches story of Hong Kong’s development is now familiar, tracing the detailed development of the economy is a rather more speculative business than is the case for most other countries. The reluctance of the government to intervene in the economy extended to an unwillingness to collect statistics unless strictly necessary for business or welfare purposes. For this reason, for example, no official balance of payments or national income accounts are available before 1961. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) began to be calculated only from the early 1970s. The government’s interest in the external orientation of the colony is shown in the very detailed statistics of international trade, which were collected to give business intelligence on potential markets. In the absence of official records, historians and economists have generated a variety of estimates. From these diverse sources, a fairly consistent picture of the post-war development of Hong Kong can be established.

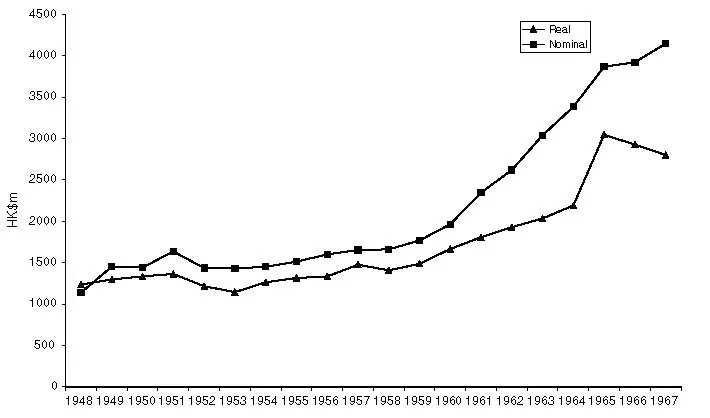

Figure 1.1 shows estimates of real and nominal GDP per capita (p.c.) from 1948 to 1967 based on Table A in the Appendix. After the initial boom associated with recovery and the Korean War, an influx of refugees combined with a trade slump in 1952–4 caused the only fall in per capita GDP in this entire period. The economy recovered gradually through the middle of the decade as industry adjusted to the new international environment. A second influx of refugees surged into Hong Kong in 1958 as a result of the Great Leap Forward and famine in China. This pushed nominal per capita growth rates down below 1 per cent.16 After 1959, however, growth accelerated and nominal GDP p.c. grew at an average rate of 10 per cent per annum (p.a.) from 1959 to 1965. Much of this growth appears to have been achieved through high rates of Gross Domestic Capital Formation, which averaged 12 per cent of GDP in 1948–58 and 20 per cent of GDP in 1959–65. The economy suffered a series of setbacks due to the banking crisis in 1965, the collapse of a building boom, the imposition of an import surcharge on Hong Kong goods by Britain, and the political disturbances of 1966/7. These events reduced the rate of growth considerably, but by 1969 the annual growth rate had returned to 16 per cent p.a.

Figure 1.1 Real and nominal GDP p.c. 1948–67.

A variety of estimates of the sector breakdown of GDP are shown in Table 1.1.17 These estimates suggest that the financial sector directly contributed about 10 per cent of GDP at this time. Chang reckoned that about half of the financial sector’s output was from banking, 10 per cent from insurance, and the rest from real estate and business rental.18 In comparison, the share of financial services in GDP in the 1970s fluctuated between 15 per cent and 22 per cent according to official estimates, rising to 26 per cent by 1995.19 Employment in the financial sector is relatively small since it is not a labour-intensive activity (note the large proportion of the workforce engaged in manufacturing). By 1975 only 2.2 per cent of the workforce was employed in the banking, finance and insurance sector, although this increased to 5 per cent by 1995.20

Chau calculated the growth of the various sectors of the economy based largely on Chang’s estimates.21 Income from banking was assumed to grow at the same rate as revenue-producing assets invested locally. Income from property was calculated from the growth of revenue from rates. Insurance income was assumed to grow at the same rate as international trade. These estimates (albeit sketchy) suggest that the rate of growth of the financial sector was slowing down through the 1960s, but was still persistently higher than the growth rate of manufacturing output. On average through the 1960s, Chau calculated that manufacturing contributed to 34.5 per cent of GDP growth and the financial sector contributed 13 per cent.

McCarthy and Johnson suggest a variety of ways in which an IFC may affect the domestic economy of the host, by contributing indirectly to GDP.22 The potential benefits relevant to Hong Kong include local expenditure on wages and incomes, a more skilled labour force, tax revenue, capital gains for local property-owners, more efficient local banking, and the development of ‘business tourism’. The costs include the rise of rental and property prices, and the ‘squeezing out’ of local financial institutions. The direct gains through wages are limited because the financial sector is not labour-intensive, and many of the highest paid employees are expatriates, rather than from the local population. In 1961 there were 164,303 workers in the categories of Managerial, Professional, Office and Clerical in Hong Kong. The large number of Chinese-controlled banks engaged in international financial activity suggests that the gains to the local population might be more significant than was the case in other centres such as Panama. Johnson also suggests that the construction industry benefits from the IFC, although in Hong Kong’s case construction booms arose from the expansion of domestic manufacturing as well as the financial sector. Certainly property and real estate markets soared in the 1960s, due partly to speculative capital attracted to the IFC, but this could be destabilising for the economy as a whole because of periodic slumps in the market. Tax revenue related to the IFC is difficult to specify. Interest tax totalled HK$96 million between 1950 and 1965, but was only 5 per cent of tax revenue in 1965, and 1 per cent total government revenue. Since one half of total bank deposits were probably from overseas, about HK$48 million was generated for the government. It is not possible to isolate the profits and property tax related to international financial activity. The IFC probably did contribute to the development of Hong Kong’s services as a business tourism centre, but again it is difficult to isolate this from the role of the manufactured export sector, which also attracted tourists through regular trade fairs. The impact of the development of the IFC on domestic financial institutions, and its effects on the provision of capital for industry will be discussed in Chapter 6.

Table 1.1 Output and employment by economic activity (%)

The 1950s and 1960s are best known as the era in which Hong Kong abandoned its entrepot role and became a manufacturer. By 1960, 85 per cent of Hong Kong’s domestic exports were manufactured goods, which amounted to over HK$2.4 billion. Table 1.2 gives some indication of the growth of manufacturing, particularly in textiles.

The protection from Chinese competition afforded by political events, combined with support from the Hong Kong government, might be interpreted as the ‘import-substitution’ phase of Hong Kong’s industrialisation. Until 1949, the government imported and rationed scarce cotton yarn to keep its price down in order to protect the textile industry. Prices subsequently dropped due to dumping of Chinese and Indian stocks, but began to rise again during the Korean War boom in the second half of 1950. The government then imposed a ban on re-exports of yarn from Hong Kong until 1953 to protect supplies to local factories. The government also imposed a ban on Japanese cotton imports to protect domestic producers. The early support offered by the government through these policies is generally ignored by those critical of the state’s neglect of industry.23

Table 1.2 Some indicators of the growth of Hong Kong manufacturing

Textile weaving dates back to 1922, when the first factory was opened in Hong Kong by the East Asia Clothing Factory of Macao.24 Power looms were first i...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Tables

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Hong Kong in the international economy

- 2 Hong Kong and China 1945–51

- 3 The banking system

- 4 Foreign exchange markets

- 5 The gold market, the stock exchange and insurance

- 6 Hong Kong as an international financial centre

- 7 Epilogue and summary

- Notes

- Bibliography