This is a test

- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Political Economy of Oil and Gas in Africa

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The evolution of the Nigerian oil and gas industry spanned about a century during which several challenges were encountered and surmounted by major International Oil Companies (IOCs). This book provides a thoroughly researched guide to the Nigerian oil and gas industry. The author examines the increasing role of Africa in the contributi

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Political Economy of Oil and Gas in Africa by Soala Ariweriokuma in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1 Oil and gas in Africa

Introduction

Africa is abundantly endowed with oil, gas and other energy resources. Exploration of these resources in the continent can be traced to early 1900; however, commercial discoveries were only recorded in the 1950s. In the 1970s consuming countries relied on oil from the Middle East for major industrial and domestic activities, but recent events in the Middle East have necessitated the shift of activities of IOCs to oil bearing areas in Africa. A hot spot in the region is the Gulf of Guinea, which is estimated to have 5–12 billion barrels of crude oil. The continent is technologically backward; therefore oil and gas exploration and exploitation depends on external entrepreneurial initiatives. Experts are of the view that the continent at current levels of production accounts for 10 per cent and 8 per cent of global oil and gas reserves respectively. Global interest in the industry has steadily increased, accounting for the expansion in crude oil production from less than 1 mmbd in the 1950s to well over 10 mmbd in 2006. The degree of contribution of each country varies, which in part determines the different levels of inflow of capital into the upstream sectors of the region. The industry in each of the producing countries presents unique opportunities and challenges: in the case of Nigeria it is observed that the terrain covers land, swamp, shallow continental shelf and Deep Water. Nigeria, Libya and Algeria have long been associated with hydrocarbon production and also belong to the OPEC family. Egypt, on the other hand, is actively involved in the African Petroleum Producers Association (APPA). In recent years Angola, Sudan and Equatorial Guinea joined the ranks of oil producing countries in the region. In view of the diversity of the continent, it can be contended that the political economy of the oil and gas industry in Africa covers a broad spectrum, with each shade of the spectrum exhibiting distinct characteristics which demand thorough analysis. Nigeria serves as the primary focus of the discussion; however, it can be posited that contextually the various oil and gas industries in the continent have political, economic and social/cultural links. The formation of APPA is an eloquent attestation of these links. In view of these relationships it would be necessary to briefly examine the upstream activities of selected countries, namely Algeria, Libya, Egypt and Angola, in order to establish basic characteristics in the evolutionary and operational patterns of the oil and gas industries in Africa. Such an analysis would provide an opportunity to estimate the potentialities of the various industries and the underlying political forces that shape them.

REGIONAL CRUDE OIL PRODUCTION

Algeria

Oil and gas activities

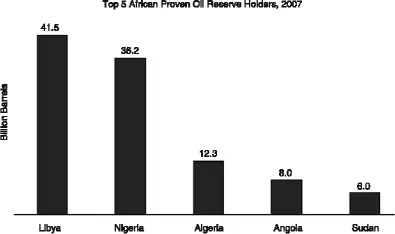

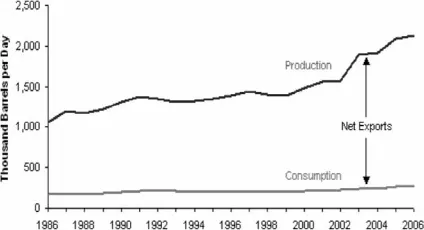

Algeria started oil and gas production around 1956 and currently has proven reserves of 12.3 billion barrels of crude oil (Figure 1.1). It is ranked third largest producer in the continent. An estimated 70 per cent of the proven reserves are located in the Hassi Messaoud Basin, while about 30 per cent are found in Berkine Basin. In 2006, average daily production amounted to 1.4 million barrels. In addition 440,000 b/d of lease condensate and 305,000 b/d of natural gas liquids (NGL) were produced from active fields. Available data (Figure 1.2) indicates that aggregate production of hydrocarbons (i.e. crude oil, condensates and NGLs) in 2006 amounted to 2.13 mmbd. Algerian Sahara Blend is rated high grade hydrocarbon with a sulphur content of 0.1 per cent and has a 45° API rating. Prior to 2005, the industry was dominated by Sonatrach, the NOC. The role of Sonatrach was modified through the enactment of the hydrocarbon reform bill. The bill paved the way for foreign participation and empowered the NOC to acquire at least 51 per cent equity interest in new oil and gas concessions or joint venture (JV) companies in the industry.

Figure 1.1 Proven oil reserves of reference countries.

Source: http://www.eia.doe.gov. EIA Country Analysis Publication, 2007

Source: http://www.eia.doe.gov. EIA Country Analysis Publication, 2007

Figure 1.2 Algerian crude oil production and consumption.

Source: http://www.eia.doe.gov. EIA Algeria Country Analysis 2007

Source: http://www.eia.doe.gov. EIA Algeria Country Analysis 2007

Sixth licensing round

In 2005 the NOC executed its sixth licensing round which placed on offer ten Blocks for IOC participation. On the whole, 54 companies expressed interest and took part in the bid process. BP won three concessions while Shell, BHP-Billiton and the UAE-US consortium won two concessions each. Sonatrach attained a production level of 440,000 b/d at the Hassi Messaoud field in 2006, by far the highest individual company. It is also associated with the Hassi R’Mel field (north of Hassi Messaoud) which has an estimated crude oil production of 18,000 b/d. Other fields are located at Zarzaitine, Ben Kahla, Ait Kheir, Tin Fouye and Tabankort. The enactment of the hydrocarbon reform bill paved the way for active foreign participation in the industry and first among the foreign producers was Anadarko, with a production capacity of 500,000 b/d. The company also operates in Ourhound (Eastern Algiers) and Hassi Berkine South fields which collectively account for 450,000 b/d. The NOC continues to inject new investment capital into its operations, thereby paving the way for the simultaneous development of seven fields in Block 208 of the Berkine Basin. Production from these fields was due to come on stream in 2008.1

Libya

Background

Oil exploration and production activities started in Libya in 1953, shortly after the discovery of oil in Algeria. The Libyan General Petroleum Corporation (Lipetco) was founded in 1968 through a royal decree. Following the overthrow of the monarchy in 1969 Lipetco was restructured under Law no. 24 of 3 March 1970 to form the Libyan NOC, which was mandated by the decree establishing it to engage in exploration and production of oil through its affiliate companies or in collaboration with IOCs. The dominant mode of operation was the Production Sharing Agreement (PSA). Structurally the NOC had fully-owned companies which were responsible for carrying out exploration, development and production activities. These companies were also charged with responsibility for local and international marketing of crude oil and products. The NOC’s primary export markets were Germany and Spain. Initially the NOC signed a participation agreement with selected IOCs but these agreements were subsequently converted to PSAs. The oil and gas industry in Libya progressed smoothly until the PANAM Flight 103 bombing incident over Lockerbie, Scotland in 1988. Libya was accused of sponsoring terrorist activities which led to the bombing of the passenger aircraft. Following this incident UN sanctions were imposed on Libya on 31 March 1992. Consequently, oil and gas activities in the country suffered a serious setback and the NOC did not enter into new collaborative activities with foreign companies in the 1990s.

Lipetco in the 1960s

The activities of Lipetco in the 1960s and 1970s were primarily defined by political and economic events. In the early 1950s Libya was essentially a subsistence agrarian economy with modest to low income from the sector. The discovery of oil in 1957 dramatically changed the fortunes of the country and annual growth rate progressed to about 20 per cent in the 1960s. The new revenue stream from oil became the vehicle of growth, thereby necessitating elaborate structural changes in the economy. The outcome of one of these changes was the creation of Lipetco. In 1969 the monarchy was overthrown, paving the way for Colonel Muammar Gadaffi to become head of State. The new government espoused self-reliance and Socialist ideologies. These initial manifestations of the new regime indicated government intention to participate actively in economic planning, policy formulation and other broader issues of national interest. The need for the new regime to actively participate in governance was signalled by the introduction of more aggressive policies targeted at ownership of oil assets and a new pricing policy. The strategy of price control through production cuts was introduced by OPEC and was widely embraced by the members. Libya joined OPEC in 1962 and progressed to be an influential member and the seventh largest producer in the organisation in 1977, but this position could not be sustained in the era of UN sanctions. JV agreements were signed between Lipetco and the IOCs, the first with French companies ERAP (later ElF), and SNPA (Aquitaine). In 1969 additional JV agreements were signed with Royal Dutch/Shell, ENI’s Agip and Ashland Refining.

JV activities in the 1970s

As pointed out earlier, Lipetco was transformed into Libyan NOC through Law no. 24 of 1970. The law restricted the formation of new JVs with IOCs. Alternatively, Production Sharing Agreements (PSAs) were introduced as the new mode of engagement of foreign oil companies. Production sharing was at a ratio of 85:15 onshore and 81:19 offshore. In July 1970 a new law was enacted vesting in the NOC the authority to market all oil and gas products in Libya. In order to carry out this mandate Brega Petroleum Marketing Company was established as a subsidiary of the NOC. The foreign owned companies – Shell, Ente Nazionale Idrocarburi (ENI) marketing subsidiaries and Petrolibya were transferred to the NOC. The operations of Brega (the marketing company) would under these circumstances be responsible for importing, distributing and marketing of petroleum products in the country. The NOC aggressively pursued the policies of the government including the new higher oil prices policy and PSAs. These policies were objectionable to IOCs, who put up stout resistance. The government was resolute and companies were initially given the opportunity to surrender voluntarily participatory interest in their concessions in compliance with the new partial nationalisation policy of the government. Some companies voluntarily complied while others continued on the path of resistance. Non-compliant companies were subjected to stiff political pressure to relinquish the concessions.2

Crude oil production

Aggressive crude oil exploration in Libya commenced in 1953 and the first oil was discovered at West Fezzan in 1957. However, Esso (later Exxon) made the first commercial discovery in 1959 at Zaltan. The Zaltan field was linked with export facilities at Marsa al Burayqa in 1961. The early discoveries were followed by others which included major strikes in Sirtica Basin field, classified as one of the largest oil fields southeast of the Gulf of Sidra. The Sirtica Basin production remained a major source of crude oil until 1987. In 1969 another major discovery was recorded at Sarir, southeast of Sirtica Basin field. In addition to the major fields some other oil deposits were discovered in fields located in Northwest Tripolitania. The intense exploration and development activities led to the discovery of new oil deposits at the Ghadamis Basin, about 400 km southwest of Tripoli. Similar strikes were recorded in 1974 at fields located about 29 km northwest of Tripoli. It is important to note that in 1977 major oil exploration activities were localised in the offshore fields. In 1987 NOC and Agip collaborated to put on stream the Bouri field. It is significant to note also that the settlement of the maritime boundary disputes between Libya and Tunisia in 1982 and that of Malta in 1983 expanded the scope of offshore exploration activities. The settlement of these disputes was considered strategic in an area believed to hold about 7.5 billion barrels of extractable crude oil. Oil production in 1984 was principally governed by the Petroleum Law of 1955 which was subsequently amended in 1961, 1965, and 1971. In an effort to expedite national development, the concession contracts had enshrined in them progressive nationalisation of foreign operations in the industry within a period of ten years. In this regard the government placed its share of operations at 25 per cent, with a provision for rising to 75 per cent. The PSA with Esso (first exporter of Libyan crude oil in 1961) being among the first, it served as a litmus test for the profitability of the PSA model. The Esso experiment proved successful and this encouraged many companies from Europe and the US to sign similar agreements with the Libyan government. Available records indicate that in 1969 about 32 companies agreed concession agreements with the NOC. The government intensified its nationalisation objectives in the industry and the NOC actively served as the vehicle for the execution of the nationalisation agenda.

The post-revolutionary nationalisation programme commenced in December 1971. The first casualty in the exercise was British Petroleum in the BPBunker Hunt Sarir field. Industry experts described the action against BP as a retaliation for Britain’s failure to prevent Iran from seizing three small islands in the Persian Gulf believed to belong to the United Arab Emirates. In 1972 the NOC requested a 50 per cent participatory interest in the Bunker Hunt operations. The request was denied, which led to total nationalisation of all Bunker-Hunt assets in 1973. In 1972 ENI and the NOC mutually settled for 50 per cent government participation. Similar discussions took place between the NOC, Occidental Petroleum Corporation and Oasis Group. Occidental conceded to the NOC the purchase of 51 per cent of the assets. In 1973 Oasis Group owned by Continental Oil (33.3 per cent), Marathon (33.3 per cent), Amereda (16.6 per cent) and Shell (16.6 per cent) agreed to a 51 per cent assets acquisition by the government through the NOC. The government pressed ahead with the nationalisation programme and on 1 September 1973 it made a blanket announcement confirming the acquisition of 51 per cent interest in all the remaining companies in the industry. Shell opposed the government acquisition of its interest in Oasis and initiated legal proceedings against the Libyan government. The government took exception to the action of Shell and as a result nationalised all its assets in 1974. The Libyan-American Oil Company, Asiatic Company and Texaco had their assets nationalised and were paid compensation in 1977. The unfavourable posture of the government to IOCs forced Exxon to pull out of Libya in 1981. Mobil took a similar action in 1982 by withdrawing from its operations in the Ras al Unuf system. The withdrawal of these companies from the Libyan upstream sector indirectly expanded the scope of operations and control of the NOC. In 1987 the total equity of the NOC in the industry was estimated to be about 70 per cent. The Libyan oil industry suffered a serious setback during the period of isolation emanating from the UN sanctions against the oil rich country. The sanctions imposed in 1992 lasted until April 1999. Upon the lifting of the sanctions the country initiated revisions of the petroleum regulatory laws. Available data also indicates that about 135 Blocks were earmarked for bid/offer to the IOCs. The situation in the country has improved and a good number of IOCs have returned to Libya to reactivate the upstream sector. In 2004 Libyan crude oil production stabilised at about 1.2 mmbd. In view of the enhanced production activities, it was projected that production would attain 2 mmbd in 2007.3

Egypt

Oil and gas production

Egypt is a significant oil and gas producer and long standing member of the APPA. It has aggregate crude oil reserves of 3.7 billion barrels. Average daily production increased over the years and peaked at 576,000 b/d in 2005, but recent trends indicate a decline in production which is taken seriously by the government. In this regard, appropriate steps were taken to introduce cutting edge technology to the exploration, and production programmes and Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) techniques have also been adopted as options for slowing down the declining rate of production. Oil is derived from four main territories, namely: the Suez Canal, which accounts for 50 per cent of recoverable oil; the Sinai Peninsula; and the eastern and western deserts. The Gulf of Suez Petroleum Company (GUPCO) is the producer in the Gulf of Suez Basin under a PSA arrangement between BP and the Egyptian General Petroleum Company (EGPC). Production in the GUPCO fields commenced in the 1960s and increased until about the mid-1980s when regression in production was apparent. Petrobel, ranked the second largest producer in the country, is a JV company involving EGPC and ENI of Italy. Its active fields are located at Belayim, proximate to the Gulf of Suez. It is also actively engaged in the implementation of EOR programmes in order to stem production decline in the fields. Exploration and production activities in the industry are also undertaken by the Suez Oil Company (a JV involving EGPC and Deminex), Badr El Din (EGPC and Shell) Petroleum Company, El Zaafarana Oil Company (EG...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

- About the Author

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Oil and Gas in Africa

- 2. Nigerian Oil and Gas Industry

- 3. Petroleum Geology of Nigeria

- 4. Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC)

- 5. Upstream Sector

- 6. Marginal Field Development

- 7. Oil Field Service Companies

- 8. Nigerian Content Development (NCD)

- 9. The Joint Development Zone (JDZ)

- 10. Refineries and Petrochemicals – DS

- 11. Products Marketing Companies – DS

- 12. Gas Monetisation

- 13. Elements of Petroleum Law

- 14. MOU and JV Operations

- 15. The Niger Delta

- 16. Environmental Pollution

- 17. Shipping and Cabotage Practice

- 18. Privatisation and Liberalisation

- 19. Investment Opportunities

- Appendices