![]()

1 The nature of transport

Our study of the freight system starts with its central core, transport. The nature of transport seems straightforward and is rarely examined in depth. However, it is fundamental to understanding the broader economic and political issues.

The transport domain

The general definition of ‘goods transport’ seems to present no difficulty: it is an everyday expression. The dictionary, as we saw in the Introduction, defines ‘transport’ as ‘taking or carrying something from one place to another’, while ‘goods’ are ‘movable items that could be subject to commerce or a transaction’. Transporting goods is therefore taking or moving to another place items designed to be bought and sold. However, ‘transport’ and ‘goods’ are worth examining more closely.

Transport in the economy

In practice, the economic field covered by the word ‘transport’ is narrower than dictionaries say. Some things are moved without it being regarded as transport: tap water is distributed, machine tools moved within a workshop are handled. Moreover, administrative and statistical practices for measuring transport movements leave out, or treat differently, some specific, sizeable types of traffic.

A concept that needs specifying

Water is considered transported if it is bottled, reaches the consumer by a transport system (rail, road), and is sold in shops. Running water, and liquids or gases generally, are different. ‘Tap’ water that is treated, distributed and sold by a specific organization through a network of pipes does not come within the professional and technical field of transport but that of water production and distribution. Similarly, piped gas (but not bottled gas) and electricity (but not batteries or accumulators) are industries in which production, distribution and usage require a specialized technical network, just as the collection and treatment of waste water is part of a sewage network.

Yet the transport domain is not economically distinct from the domain of ‘pipes’ and conduits (for oil, various gases and even bulk powders or electricity cables). Once it became possible to transport electricity over long distances without excessive losses, energy transfers between regions changed in character: heavy loads of coal and other fuels were replaced by electricity travelling along wires. Similarly, after an oil pipeline is laid, the movement of petroleum products along parallel routes by traditional surface transport (rail, road, waterway), falls. There is both competition and complementarity between traditional transport and specialized pipe and cable transport. While ordinary transport is generally the responsibility of a transport minister, petroleum and gas pipeline transport might come under an energy or industry minister.

Transport statistics may or may not include petroleum and chemical products transferred by oil and gas pipeline (piped drinking or non-drinking water never is). Care must therefore be taken when comparing the use of the various transport techniques, especially across different countries.

The boundaries set by statistics

As well as the conceptual nuances on the transport domain there are technical limits to statistical systems.

Agricultural vehicles are registered differently from freight vehicles in many countries, and their movements are not covered by road freight surveys used to produce statistics. In contrast, the carriage of agricultural products in ‘normal’ vehicles is included in transport accounts. Some common transport vehicles are not covered systematically by the surveys, in particular vans or light goods or utility vehicles (delivery vans, transit vans and pickups), despite their growing role in express parcels and home deliveries.

The transport of waste, including household refuse, is generally short-distance and part of a special chain of collection and treatment in a complete branch of industry separate from transport. Agricultural waste products, if not treated on the farm, are mainly transported by farmers, and therefore not measured. Only waste carried independently of its treatment is considered to be transported. On the other hand, the new specialized form of logistics called ‘ reverse ’ or ‘ return logistics ’, collecting and handling surplus or returned goods from retailer or manufacturer, counts as transport.

Postal activities (see Box 1.1) move goods in space and merit the title of transport. Even setting aside post office staff in financial roles such as banking, the Post Office is usually the largest goods carrier in a country, in terms of financial turnover, number of objects, number of staff (not counting external contractors), even if not in terms of tonnage. The Chinese Post Office has 720,000 staff, the United States Postal Service 620,000, the UK Royal Mail Group 193,000 and the Japanese Post Office 100,000. Yet the Post Office typically comes under a ministry of post and telecommunications or industry, and the economic value of its production is separated in national accounts from the transport industry.

The partial dismantling of the postal monopoly, the entry of private operators into segments of the mail market (mainly express and packets) and the expansion

of post offices, in the opposite direction, into the market domain (parcels, express delivery), blurs the historic separation between the transport and postal worlds. The extent of regulatory and professional separation varies between countries. Associations, alliances and mergers as well as competition between postal enterprises and transport enterprises are accelerating at European and global levels. The German postal service (Deutsche Post) is currently the prime world operator of freight and logistics in terms of turnover, through its specialized subsidiary, DHL. Postal services have economic and political importance in Europe, because they fall within the EU’s definition of ‘services of general economic interest’, that is, public utilities or public enterprises.

The usual transport analyses also omit goods transport operated by households in small vans or cars. Though it comes into the category of self-consumption by end-user rather than the professional and business sphere, its role is significant. Major retail distribution is organized around a motorized clientele, and the final leg of transport by households, between hypermarket and home, replaces professional delivery by local shops, whose business has declined. A hesitant move back to town centre shops is happening, however, often in very modern forms, as in the case of Japanese 'combini', small self-service stores, often open 24 hours a day. Simultaneously, home deliveries are expanding because of the spread of internet shopping (‘e-business’).

Transport and social custom

Defining transport and identifying the economic field it covers is not just semantics – nor purely technical. Transport needs objects to be displaced spatially before it acquires a certain autonomy from other technical manufacturing or commercial activities. This technological autonomy is often accompanied by economic autonomy, via the intervention of specialized professionals.

Use of public space is another criterion for identifying the transport domain. Infrastructure occupies a technical and legal space usually dominated by public authorities, while transfers across a private site are regarded more as handling than transport and are not subject to the same level of regulation.

Categorizing certain ways of moving an object in space as ‘transport’ is therefore based on social usage or custom, and can vary from one type of movement to another and is likely to evolve.

Merchandise, goods and production

The designation of transported objects by the term ‘merchandise’ is in common use in Romance languages: transport de marchandises in French, transporte de mercancias in Spanish, trasporto merci in Italian, and so on. In contrast, ‘Anglo-Saxons’ more commonly talk about the transport of ‘goods’: Güterverkehr in Germany or goods transport in Britain, where it can, in law, mean merchandise as well as movable property.

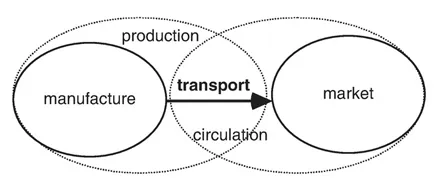

Implicitly, ‘merchandise’ describes transport’s essential function: it links the world of production to that of trade; it enables products to be transformed into marketable items. Karl Marx adopted this very position when he defined transport ‘as a continuation of a process of production within the process of circulation and for the process of circulation’ (Marx 1867/ 1956: Part I: 6.3). It means that, from one angle, transport is a production operation (this point is fundamental); but, at the same time, it takes place outside the usual production arena. The transport process, the physical circulation, is set within the market process of circulation and placed at its service.

Though simple and persuasive, this formula needs examining. Strictly, applying the term production just to the sphere upstream of transport is erroneous if transport is considered a productive activity too. The term manufacturing for industrial products (like growing and raising for agricultural products or extracting for raw materials) is preferable to the overly generic term production (see Figure 1.1 ).

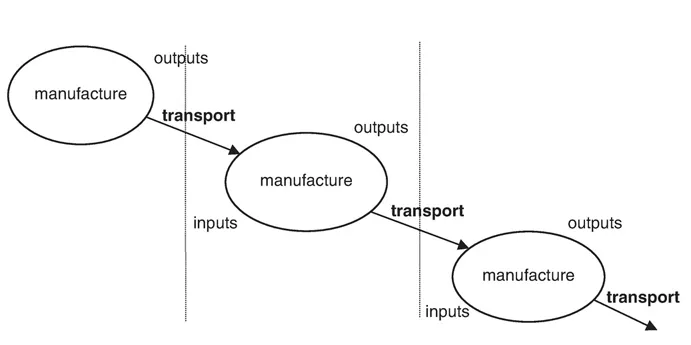

Moreover, manufacturing is generally not restricted to a single operation, completed on one site. It is segmented into stages that, on the principle of the division of labour, are often carried out by different firms on different sites. Each stage relies on the purchase of a flow of supplies, or inputs. There is transport upstream of manufacturing, not only downstream. Indeed, the purchaser’s upstream supply is the provider’s downstream distribution (the inputs of one are the outputs of the other),

Figure 1.1 Transport, production and market.

and the production chain alternates between manufacturing and transport operations, possibly with warehousing operations in between (see Figure 1.2 ).

Alternatively, manufacturing may be split into stages in different places but achieved by a single firm. The products then move from one transformation site to the next within the corporate boundaries of the firm, in the way they move from between workshops within the spatial boundaries of the factory, or between machine tools within the boundary of a workshop. Fundamentally, transport is always handling, over a longer or shorter distance. The aim of production logistics is to manage these manufacturing flows (simultaneous flows of intermediate consumption, components and products, and flows of information that steer and regulate the system). During manufacture, product ownership does not change every time their location changes; their physical circulation does not imply market circulation; they are not merchandise, correctly speaking, even if they will become that once manufacture is complete.

Note that inter-site transport within a company is often carried out by the company itself, using its own resources. Not only is the transported product not on the market, but the transit is not treated as in the transport market. It is nevertheless subject to official transport regulations, especially when using public roads.

Figure 1.2 Supplies, distribution and transport in an industrial production line.

Figure 1.3 Transport and industrial production.

The role of transport in production lines – from the extraction of raw materials to the final sale, via the intermediate manufacturing of semi-finished products and supply of materials – is definitely not limited to linking the production and market worlds. At each production stage, there is transport before, after and even during, whether the product is traded when passing from one owner to another or not. The development of logistics – supply logistics, production logistics, distribution logistics, even integrated logistics – confirms that producti...