1 Procurement and the chain of supply

A general framework

Stefan Markowski, Peter Hall and

Robert Wylie

As noted in the Introduction, procurement is another word for describing the activity of purchasing or acquisition, and defence procurement refers to these activities in relation to providing a country’s national security. Defence procurement and the defence industry policy associated with it thus operate in the broad context of defence production and this chapter offers a framework for considering the relationships involved. In the next section, ‘Defence products and capabilities’, we present a bedrock model of the production of national security (defence) that focuses on the process that progressively converts intermediate inputs into final products. This section is primarily concerned with what is produced as a basis for understanding what is procured and with what implications for industry suppliers. The production of national security occurs within what we call the defence production chain which describes the physical process of national security production. To stylise the production process, we assume ‘Defence’ (the National Defence Organisation, NDO) to be the ‘producer’ of national security. In most countries, the NDO combines military and civilian elements as administrative and logistic capability involves the employment of civilian public servants as opposed to the military (in-uniform) public servants who are either drafted as conscripts or employed under military-specific contractual arrangements.

The NDO is a component of Government; the latter is ultimately responsible for the provision of national security and the allocation of resources to the NDO to carry out its tasks. However, the NDO may not produce all national security, some of which may be ‘imported’ from allies (see below) or produced by other government agencies (e.g., homeland security) and, increasingly, by private security firms.1 The distinctions between the publicly and privately produced activities and combat-related and other support operations have, however, become increasingly blurred. Such complications are initially ignored in our stylised representation, or model, of the defence production chain but will be considered later in the book.

In the stylised model, the capital inputs and consumables needed to produce national security are sourced from Industry, which in some cases may be located partly or wholly within the organisational boundaries of Defence itself (see below). Similarly, some (or all) capital inputs and consumables may be imported from other nations. Human resources are obtained from domestic Households (either by conscription or through labour markets). They can also be imported in the sense that members of the defence force may be hired through international labour markets (e.g., the French Foreign Legion). This admittedly stylised setting is useful for considering a number of concepts fundamental for the discussion of defence procurement.

To respond to military contingencies, Defence must develop and draw on its military capabilities, that is, acquire the assets and know-how needed to undertake the activities required by Government under various military and civilian contingencies. Military capability calls for human and non-human (materiel) inputs, technical war-fighting knowledge and organisational structures. Defence procurement is about acquiring the non-human, physical elements of capability, the inputs needed to form new or to modify/sustain existing elements of military capability. These products may include simple civilian consumables and durable goods (e.g., photocopying paper and office furniture) and complex civilian capital goods (such as airliners and super-fast computers); simple military equipment (such as handguns) and complex military systems (e.g., fighter planes and command and control networks); and civil and military equipment services (for example, services provided by leased military aircraft or equipment maintenance provided by contractors).

The following section, ‘Value creation’, introduces the notion of value into the analysis and discusses how the defence production chain may also be interpreted as a chain of value creation and value adding.

Next, in ‘Actors and decision-makers’, we revisit the defence value-adding chain to examine the organisational decision-takers driving the production process. Given our focus on defence procurement and industry, we are mostly interested in the upstream suppliers of military materiel and those elements of Defence involved in forming military capabilities. In this context, the defence value-adding chain can be represented as the defence supply chain – the emphasis shifts from what is produced to who is doing it.

The NDO may take different organisational forms depending, for example, on whether its combat arm is structured as a single organisational entity or fragmented into Services and on how military and civil elements work together. The relationship with Government is particularly important as the NDO is a government agency dedicated to the production of national security. In this book, we are primarily concerned with the procurement-related tasks of the organisation. There may be a single, specialised unit within Defence responsible for all defence procurement – the Defence Procurement Agency (DPA). Or, procurement activities may be dispersed between operational elements such as the Services, or centralised within a specialised but organisationally detached agency. In the latter case, the detached agency may be Defence-specific (as in Australia) or it may act as a procurement agent for a number of government departments, including Defence as, for example, in Canada.

The procurement agency places orders with industry suppliers at home and abroad. The success (or otherwise) of the DPA in meeting the requirements of the Services depends on the efficiency and effectiveness of Industry and the relationships between industry suppliers and procurement personnel. Capital equipment and consumables may be produced in-house (e.g., in shipyards and arsenals owned and operated by Defence) or sourced from outside Defence. Thus, Industry, an upstream producer of intermediate inputs into the formation of military capabilities, may take many organisational forms: from complete integration of upstream industrial support into the NDO’s organisational structure, to defence-focused private contractors (domestic and foreign), to private and public firms for whom Defence is one of many customers.

In the final section, ‘Supply chain links and relationships’, we focus on how entities involved in the production of defence are linked and interact with each other. We note first that when the interface between the DPA and Industry is market-mediated, the relationship between buyer and supplier is influenced by industry structure. A supplier of a product for which no close substitutes are available, and facing no threat from potential industry rivals, is potentially in a strong position to use its market (monopoly) power to demand higher prices, determine quality standards, or allow delivery schedules to slip. However, when the DPA deals with many sellers of close substitutes, it may rely on competition between sellers to ensure that prices charged are reasonable and product quality and the timeliness of deliveries are not compromised. Also, when the DPA is a very large or the only (monopsony) buyer of a product, it is potentially in a strong position to impose its terms on the supplier(s).

In this section we also outline the nature of transactions associated with the acquisition of goods and services by the NDO from Industry, that is, how procurements are arranged and executed:

- the nature of the business deal involved in the transaction, its scope, scale and timeframe, the nature of exchange involved (e.g., goods-for-money or barter), and the associated consideration (price);

- the contract determining rights and obligations of the parties in the context of the transaction;

- the relationship between the parties following the signing of the contract.

These issues are examined in greater depth in later chapters.

The present chapter is only intended to provide a framework for the subsequent discussion of defence procurement and the relationship between Defence and Industry, and many specific aspects of the defence production chain will be examined in greater detail in other parts of this volume.

Defence products and capabilities

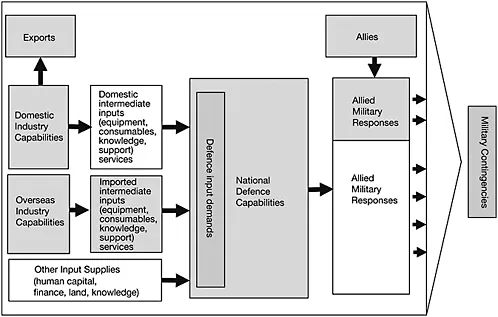

Figure 1.1 is a stylised representation of the defence production chain.In Figure 1.1, domestic production runs from left to right, from upstream industry capabilities and the production of outputs that serve as intermediate inputs into downstream military capabilities and the production of the final output, national security. Arrows indicate flows of goods and services. Production capabilities, inputs and outputs are represented as boxes. The logic implicit here is that the requirement for the end product (i.e., military responses to threats to national security) determines inputs required by downstream defence activities and, thus, the outputs, activities and capabilities of upstream producers. If the final product was well defined and had a clear and observable market value, it would be relatively straightforward, in principle, to work out the derived demand for defence intermediate inputs and their associated industry capabilities. But the contingent nature of national security and its ‘public good’ characteristics complicate matters considerably.

National security as a contingent good

The end product, national security, may be viewed as a set or vector of final outputs (military responses) produced to counter threats to or violations of national sovereignty. Broadly, this set of final outputs comprises two sub-sets, one related to deterrence and the other to wartime deployment of military capabilities. Deterrence-related outputs comprise the (usually unobservable) instances of prevention of hostile acts against the country and its interests, which would have occurred if relevant military capabilities had not been in place. Deployment-related outputs comprise the actions Defence takes to counter threats to, or violations of national sovereignty, and provide other forms of service at the direction of Government (e.g., peacekeeping). The specific services comprising the deployment-related end products are contingent on the state of the world – military contingencies. These end products are only produced if particular military contingencies actually materialise.

Figure 1.1 A stylised defence production/value chain

Ex ante, it is impossible to specify every relevant military contingency or, as we shall also call it, scenario. The latter may include global nuclear war, ‘conventional’ local wars, terrorist activities, and minor military emergencies during peacetime (e.g., intrusions into national waters or airspace, military espionage). In practice, only a limited number of scenarios can be envisaged in detail and some are better understood and thus easier to describe than others. Similarly, perceptions of the likelihood of different military contingencies can usually only be described in terms such as ‘very likely’, ‘rather unlikely’,or‘credible’ rather than in precise, probabilistic terms. The development of ‘credible’ military scenarios is an art rather than a science, highly subjective and usually involves small groups of experts with access to classified data. Judgements about the likelihood of alternative states of the world also tend to be rather short-lived, and new scenarios and strategic outlooks are often required to reflect the impact of recent events.2

However, to determine what military capabilities are required, strategic planners seeking to act rationally have little choice but to develop a set of military scenarios to shape and frame their recommendations to Government. For each identified contingency they must also consider a range of military response options. For example, to deal with a scenario of peace enforcement in a neighbouring state, a broad response may involve the dispatch of a small expeditionary force. However, there are specific options within this broad response that may differ considerably in their particulars. For example, a peacekeeping operation may either be highly labour-intensive, with a relatively large number of peace-keepers on the ground to win the hearts and minds of the locals, or highly capital-intensive (aircraft, armour, etc.) to show the force needed to intimidate troublemakers.

To make decisions about acquiring various elements of military capability, such as weapons systems and consumables, personnel and operating skills, Defence and its political masters must determine which military contingencies are most likely to occur; what they involve; what needs to be done to handle them; and, given the budget constraint set by Government, what investments in new capabilities have to be made to produce the required military responses. Thus, most end products of Defence are contingent outputs in the sense that they are only produced if certain military contingencies occur. To the extent that the production of defence end products is conditional on the occurrence of certain military contingencies, their value can be judged and assessed only ex post, once the outputs are actually produced.3 In the case of deterrence, success results in an absence of conflict and although peace may be taken as an outcome of deterrence-related national security production, it is not possible to determine the extent to which the absence of hostilities results from defence spending on particular capabilities or other factors. In peace-time, the capabilities of the NDO are not fully deployed or operational. At such times, the NDO concentrates on producing intermediate services such as training personnel, maintaining equipment, developing military response options, and so on.

National security as a public good

Many final outputs produced by Defence (e.g., deterrence, combat activities) are what economists call public goods. Such goods are characterised by non-excludability (of non-payers from consumption/use) and non-rivalry (among users – so that one user’s consumption does not reduce the availability of the good for other users). These conditions discourage the commercial, private market provision of such goods, so that government may have to arrange to supply them if they are to be provided at all (Spulber, 2002).

Publicness poses the challenge of finding a workable and reliable way of placing a value – a social value – on such goods. There are no market-generated price signals to indicate preferences for one type of public good rather than another or one type of defence output rather than another. Such choices are usually made by Government as part of a broad ‘package’ of goods and services (some highly ‘public’ in content and some not) that it promises to deliver or have delivered. When political parties contesting an election promise alternative packages of public goods, the electorate influences the mix of what is to be provided, including defence. However, the electorate is not normally involved in deciding the specific composition of defence expenditure, which it leaves to ‘experts’ in Defence and other government agencies to determine.

Despite that, governments sometimes frame their relationship with Defence as a transaction-like exchange between a buyer and a seller. In Australia, for example, the government has described itself as buying ‘outputs’ from the Australian Defence Force (ADF) to achieve desired ‘outcomes’.4 The purpose of applying this quasi-transactional framework is to provide a basis for setting targets and measuring the performance of the ADF to make it more efficient and accountable to the government (ASPI, 2006b).5 But this quasi-market exchange should not obscure the fundamental nature of national security as a public good and the attendant valuation problems.6

Contingent outputs and military capabilities

There is also an intermediate step between a NDO acquiring resources such as personnel, physical weapons and defence-related knowledge, on the one hand, and producing national security outputs, on the other. For the NDO to respond to military contingencies, it must acquire the capability or capabilities to produce military end products. The notion of capability generally refers to an organisation’s ability to undertake an activity it wishes or may be called upon to perform.7 Thus, to respond to military contingencies, Defence must generate appropriate military capabilities – it must be able to acquire and combin...