This is a test

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ecological Economics and Industrial Ecology

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Holistic in approach and rooted in the real world Ecological Economics and Industrial Ecology presents a new way of looking at environmental policy; exploring the relationship between ecological economics and industrial ecology.Concentrating on the conceptual background of ecological economics and industrial ecology, this book: provides a selection

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Ecological Economics and Industrial Ecology by Jakub Kronenberg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1 Introduction

1.1 General setting

There is a hidden story behind every product, a story of which consumers are rarely aware. Sometimes dramatic, frequently sophisticated and always very interesting for those who investigate them, these stories recount the life-cycles of products and the related environmental impacts. Policy makers in many countries have made efforts to reveal these accounts to the general public, the most comprehensive initiative so far being the Integrated Product Policy (IPP) of the European Union (EU).1 The IPP is an example of a product-oriented environmental policy – it attempts to reduce the pressure that our society exerts on the environment through targeting products. This approach is innovative in at least three ways:

- it addresses the environmental impacts arising during the whole life-cycle of products, thus engaging all stakeholders who contribute to those impacts;

- it favours solving the problems as early in the life-cycle as possible, thus avoiding pollution, rather than managing it after it has arisen; and

- it addresses those impacts in an integrated way, thus reducing the risk of shifting problems between different media (such as air, water and soil).

The IPP and other product-oriented environmental policies complement traditional environmental policy. They indicate the complexity of economy– environment interactions, using the environmental impacts of products as an example. In consequence, they underline the need to adopt an integrated, systems perspective to studying environmental impacts in all environmental policy. The IPP’s impact on economy–environment interactions is particularly significant because it extends to the common market of the EU and has the potential to directly influence products originating from all over the world.

Concerted efforts of policy makers, companies, academics, environmental NGOs, consumers and other stakeholders, undertaken since the 1970s, have led to considerable improvements in relative environmental pressures associated with particular processes or products (such as resource consumption per unit of production). However, at the same time, the levels of production and consumption have been constantly increasing, in many cases neutralizing the positive relative effects. Such a situation, when increased environmental efficiency of production brings about increased consumption eventually leading to increased environmental pressure, has been referred to as the ‘rebound effect’ (see, for example, Greening et al. 2000). As a result, a rising number of authors have started to call for the decoupling of economic growth and its environmental consequences (for example, Simonis 1989; Binswanger 1993; Azar et al. 2002) and this has become one of the central issues in ecological economics and industrial ecology. However, it has yet to be addressed in the IPP.

Although progressive and potentially very influential, the IPP seems not to have been conceptually well founded. This can be confirmed by the literature overview, which indicates that, up till now, authors referring to the IPP, and to product-oriented environmental policies in general, have tended to focus on practical rather than theoretical issues. The IPP might benefit if it were more conceptually grounded and probably, because of its relevance to sustainable development and economy–environment interactions in particular, such a theoretical grounding might be sought within the areas of ecological economics and industrial ecology.

These two areas offer a holistic perspective on economy–environment interactions, and they have a reputation of laying scientific foundations for the concept of sustainable development. As such, they can be used to make more specific the traditional definition of sustainable development (according to which it ‘meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (WCED 1987: 43)). An alternative definition, based on the analogy between the sustainability of ecological and social systems, would evoke ‘flourishing, resilience, integrity, adaptive capacity, or other similar concepts – all of which happen to be emergent properties of living complex systems’ (Ehrenfeld 2004a: 3).

Furthermore, the IPP (as presented in European Commission 2003a) links to the issues commonly raised within both ecological economics and industrial ecology, such as taking an integrated approach to policy making, working with the market and life-cycle thinking. In particular, the latter has been traditionally associated with industrial ecology.

In this book, I attempt to discuss two principal issues – that of the relationship between ecological economics and industrial ecology and that of their potential implications for the IPP. Neither of these issues has as yet received sufficient attention in the literature. The current chapter introduces the book’s central ideas, objectives, approach and structure. In addition, it offers a note on metaphors, which play an important role in both ecological economics and industrial ecology, and indeed, also in the IPP.

1.2 About this book

1.2.1 Central ideas

This book makes three innovative and to some extent controversial suggestions, explained in more detail below.

- Ecological economics and industrial ecology are closely related and, together, constitute a consistent body of knowledge.

- The IPP lacks a well-established theoretical background.

- The theoretical background for the IPP should be sought in ecological economics and industrial ecology, both of which deal with the interactions between the economic and natural systems.

For the last nine years, I have focused my research interests on the economic aspects of environmental protection, thus encompassing ecological economics and industrial ecology. While following the literature related to these areas, I have been surprised about how segregated they are, even though they deal with similar issues.

I focused my attention on business activities related to environmental protection and policy initiatives aimed at shaping those activities. Within this field, product-oriented environmental policies have interested me most, as a highly innovative and integrated approach towards shaping economy–environment interactions, involving all relevant stakeholders. The IPP provides an example of such a policy. However, although it can play a very important role (because of its scope and ambitious objectives), it seems to have developed rather spontaneously, lacking sufficient theoretical background. Instead, it appears to be based on straightforward observation of the impacts that products have on the environment and on the previous experience of separate countries with their product-oriented environmental policies.

Ecological economics and industrial ecology have been selected as a potential theoretical background for the IPP because they seem to be the closest to the general idea of this policy, especially as far as adopting the life-cycle perspective of the product’s impact on the environment is concerned. Thus, it may turn out that the IPP could be further improved by consideration of the implications of these two areas.

1.2.2 Objectives

In light of the above, the objectives of this book are twofold:

- to present ecological economics and industrial ecology as a consistent body of knowledge using the case study of the IPP; and

- to evaluate the IPP and to suggest ways in which it could be further improved from the perspective of this body of knowledge.

The conclusions from this study can be extended to other product-oriented environmental policies, as the IPP has only been used as a concrete illustration. The above objectives are novel in the sense that as yet, to the best of my knowledge, they have not been studied. Although some attempts have been made to establish the theoretical foundations of product-oriented environmental policies (for example, Ehrenfeld 1995; Oosterhuis et al. 1996; or Dalhammar and Mont 2004; see section 2.6), most authors have focused on practical issues related to these policies, such as the instruments they might use. Thus, this book not only presents what might be done to improve the IPP, but also provides the theoretical justification for these suggestions.

1.2.3 Approach

Preparing this book required reviewing a significant amount of literature related to a wide array of subjects, from the conceptual foundations of ecological economics and industrial ecology, to practicalities related to performing life-cycle assessment (LCA) and to policy making.

Having discussed the IPP and its theoretical background, I evaluate this policy and suggest how to improve it. I have generally neglected the challenges to the IPP represented by the common unwillingness of policy and decision makers to deal with environmental problems in a decisive and rigorous way. Similarly, although I have indicated some other types of challenges in relevant places, I have not elaborated on such issues. Instead, unrestricted by considerations about what cannot be achieved, I have preferred to discuss what could be done from the theoretical point of view. The main challenges to the realization of the recommendations appearing throughout this book are only briefly reported in the concluding chapter.

Converting such a vast scope of theoretical analysis into one volume cannot escape some degree of selectiveness and thus some important issues have been omitted. I decided to follow only those issues discussed within ecological economics and industrial ecology that I perceived as having direct linkage to products and product-oriented environmental policy, instead of supplying full descriptions of these areas, each of which would alone necessitate a book much bigger than this one. Also, some abbreviations have had to be made and, perhaps, for this book to be fully comprehensive, in places some further clarifications or more detailed descriptions would have been helpful. For example, only one modelling approach is presented in detail (input–output analysis, practiced extensively within both ecological economics and industrial ecology), while other frameworks might also be very useful for analyses related to the IPP. However, throughout this book, numerous references identify sources where interested readers can find more comprehensive information on the relevant subjects.

1.2.4 Structure

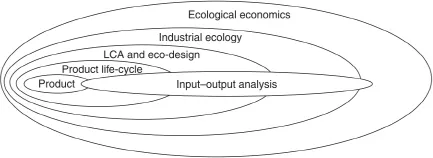

The relationships among concepts discussed in this book are presented in Figure 1.1. At the centre of the IPP’s interest lies a product and the environmental impacts associated with its life-cycle. Thus, one can associate the IPP with these two fields in Figure 1.1. Product life-cycles also constitute the focus of life-cycle assessment (LCA) and eco-design, two of the tools associated with industrial ecology. Furthermore, as industrial ecology is generally used to study economy–environment interactions, but following a specific idea of imitating natural solutions in industry, it falls into the broader area of ecological economics. The latter encompasses all efforts to study such interactions and provides a platform for interdisciplinary and diversified discussions that deal with them. Finally, in Figure 1.1, there also appears an oval representing input–output analysis, indicating its applicability to all of the other fields. Indeed, input–output methodology constitutes a widely used framework for studying economy–environment interactions, within ecological economics, industrial ecology and also LCA. As it can help to study indirect environmental impacts associated with product life-cycles, it can also be useful in the case of the IPP. One can see that moving from the broadest structures – ecological economics and industrial ecology – to more specific issues – LCA and eco-design – the theory becomes increasingly relevant to the IPP. The structure of this book reflects this gradation of relevance.

After this introduction, I present the state of development of the IPP at the end of 2006 (Chapter 2), followed by what I treat as its potential conceptual background in a hierarchically descending order. I first introduce the broadest area of ecological economics (Chapter 3) and then elaborate on a narrower area of industrial ecology (Chapter 4) and its most important aspects related to the IPP – LCA and eco-design (Chapter 5). To complete this theoretical overview, in Chapter 6, I refer to input–output analysis as a modelling approach potentially valuable for the IPP. In Chapter 7, I attempt to draw some policy conclusions regarding the desired character of the IPP, in the light of the theoretical implications presented in all of the preceding chapters. This policy analysis is illustrated with case studies, so as to explore the extent to which the current policies targeted at passenger cars, and the product-oriented environmental policy of the Netherlands, conform to those conclusions. Final conclusions in Chapter 8 close this book.

Figure 1.1 Relationships among concepts presented in this book.

More precisely, in Chapter 2, I present the IPP, against the background of other product-oriented environmental policies pursued in the EU. The IPP sets out to address problems such as increased environmental pressures resulting from an increased amount of products consumed in the market, and the complexity of products and product chains. Thus, it needs to adopt an integrated and interdisciplinary approach, based especially on enhanced cooperation between various stakeholders linked within product chains. Being still under development and being a policy framework rather than a specific policy, the IPP sets only broad objectives and merely sketches the ways in which they can be achieved. Nevertheless, it has already aroused much discussion regarding its final shape, including within EU institutions. It has been criticized for not being sufficiently holistic (or indeed, integrated), but the authors who made such criticisms have not presented any comprehensive analysis of this issue.

Ecological economics is presented in Chapter 3, as divided into the three levels of considerations addressed within it – primary (biophysical), secondary (economic) and tertiary (strategic). This division results from the interdisciplinarity of ecological economics and from the fact that it is founded on the assumption that the economy is embedded in a larger natural system, and as such is constrained by the same biophysical laws that govern the latter. Thus, any analysis performed within ecological economics has to take into account the biophysical laws. It is noted that the economic considerations of ecological economics are close to those of environmental and resource economics and (neo)institutional economics. Finally, strategic considerations, such as systems thinking or the precautionary principle, provide an overall framework within which any analysis in ecological economics must be pursued. Although ecological economics does not directly refer to products, it offers a general framework for analysing economy–environment interactions, which constitute a background for the IPP. As such, the implications from ecological economics can be perceived of as necessary for any policy attempting to shape economy–environment interactions.

Industrial ecology (presented in Chapter 4) focuses on material and energy flows between the economy and the environment. Hence, it directly links to industry, which is largely responsible for those flows, and to products, which ultimately ‘embody’ these materials and energy. Nevertheless, because of its holistic perspective, industrial ecology also includes indirect (or hidden) flows that are necessary to manufacture products (or extract resources from which they are manufactured), but do not become embodied in products as such. Thus, it attempts to study products as thoroughly as possible and supplies a set of tools that can be used to implement the IPP in practice. Moreover, as industrial ecology is based on a metaphor comparing industrial systems to ecosystems, it affords insights into how industrial activity could be organized, so as to increase its efficiency and resilience (and sustainability). For example, environmental impacts of products could be reduced if interconnectedness among stakeholders involved in product chains was higher, and, in particular, if they paid more attention to sharing information related to such impacts. Finally, in Chapter 4, I analyse the relationship between industrial ecology and ecological economics.

LCA and eco-design (Chapter 5) are examples of tools (most often associated with industrial ecology) already invoked in the IPP and that should be further supported within its framework. They rely on information and can be utilized to disseminate information among consumers (intermediate or final), and as such can influence their consumption patterns. The LCA procedure consists of four steps (goal and scope definition, inventory analysis, impact assessment and interpretation of results), which can later be used to support eco-design initiatives. The latter can improve the environmental characteristics of products. However, both LCA and eco-design focus on singular products and thus can ensure only a relative reduction of environmental pressure related to a given product. Thus, they can be further reinforced with other concepts, such as product–service systems (PSS), allowing for the reorganization of the current consumption patterns, based on an idea that it is a service that a given product provides rather than its physical form that satisfies a consumer’s need. Actually, the latter idea is widely adopted within ecological economics and industrial ecology.

In Chapter 6, I present input–output analysis. Its most important applications include studying the interdependence within economic systems and accounting for the indirect effects induced by changes in final consumption. As input–output methods represent the structure of the economy, their extensions are also valuable for studying economy–environment interactions. In particular, it can serve to complement an LCA in order to obtain a more comprehensive picture of the environmental impacts of a product throughout its life-cycle.

Chapter 7 offers an overview of the major implications of ecological economics and industrial ecology for the IPP. Also, I attempt a critical review of the IPP from the perspective of those implications. In the light of the whole study, it transpires that the IPP is not as integrated as it claims to be and that this aspect needs to be modified, if the IPP is to conform with the theoretical insights from ecological economics and industrial ecology. Among the most important of these insights is the notion that it is a service that a product provides whi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Ecological Economics and Industrial Ecology

- Routledge explorations in environmental economics

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Tables

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Integrated Product Policy (IPP)

- 3 Ecological economics

- 4 Industrial ecology

- 5 Life-cycle assessment (LCA) and eco-design

- 6 Input–output analysis

- 7 Policy analysis illustrated with case studies

- 8 Conclusions

- Appendix 1

- Appendix 2

- Notes

- Bibliography