1 Narrative on the history of macroeconomics

Classical macroeconomics

The idea captured by Adam Smith (1723–1790) in his celebrated metaphor of the ‘invisible hand’ – namely that the best economic outcome for society is obtained when each individual pursues his or her own interests (Smith 1976: IV, ii, 9) – has provided the fundamental motivating idea of economics theory and practice in liberal capitalist countries for over two centuries. In modern times it is commonly interpreted to mean that the best guarantors of national wealth and future prosperity are private enterprise and freely operating markets.

Smith, in advocating his view, was arguing against the mercantilist economic doctrines that had held sway during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. These contended that national wealth consisted of the amount of bullion amassed by a nation through trade, and implied an interventionist role for the state in promoting exports and restricting imports through tariffs and other protective devices. Smith, despite his scepticism as to the role of the state in economic affairs, did however acknowledge its importance in national defence, in protecting members of the society from injustice, and in the provision of public works and institutions which ‘could never repay the expence to any individual... though it may frequently do much more than repay it to a great society’ (IV, ix, 51). In arguing against an interventionist role for government, Smith believed that he was arguing in favour of the interests of the poor and against those of the owners of property.1

A further advance in the theory of the market-based economy was due to the French political economist Jean-Baptiste Say (1767–1832) who in 1803 stated his ‘law of markets’ which also became a cornerstone of classical economics. Say’s Law held that ‘products are paid for by products’, that is, the bringing to market of one good provided income and purchasing power which would be made effective in the purchase of other goods in other markets, or as is more directly said: supply creates its own demand. Although individual markets may be subject to fluctuations of excess supply or excess demand from time to time, these would be rapidly remedied and equilibrium restored, he believed. Taking markets across the economy overall, Say’s Law implies that there can be no general glut of commodities, no lack of aggregate demand for them, and no deficiency of full employment.

A simplified model of an economy consisting of competitive markets, as envisaged by the classical economists, can be represented as follows. Suppose that the economy consists of two sectors. The household sector provides labour to businesses in return for wages which are either spent on goods for consumption or saved. The business sector combines labour from households with other resources to produce goods for consumption, and to carry out investment in order to add to the capital base.2 Total expenditure in the economy is therefore equal to the sum of consumption expenditure and investment expenditure. Total output of the economy, equal to the national income, is equal to the sum of consumption expenditure and household savings. When the overall economy is in equilibrium, total expenditure is equal to total income, so that planned investment by businesses is equal to planned savings by households (for a mathematical description of this model, see Appendix A.1).

It is the savings of households which provide the funds that can be loaned to businesses for investment purposes. The interest rate provides the measure of the reward for thrift on the part of households on the one hand, and of the (projected) return on investment for businesses on the other. Equilibrium in the economy is thus characterized by that interest rate which reconciles the intentions of households with those of businesses. An ‘autonomous’ rise in consumption spending3 by households and a concurrent decrease in savings, for example, would result in a rise in the interest rate – because the availability of loanable funds from households has decreased – and a consequent fall in investment by businesses, until savings and investment were again equated at an unchanged level of total output, in accordance with Say’s Law. Besides assuming flexibility in the rate of interest, it is also assumed that other prices (including wage rates) are flexible in response to change.

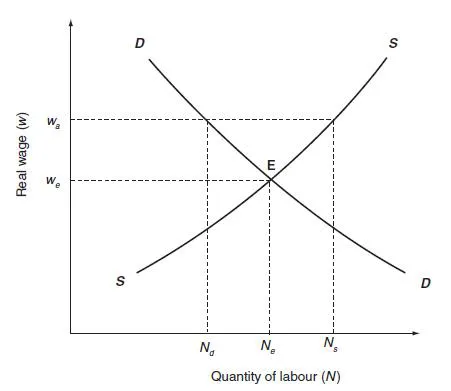

In the labour market, it is assumed that businesses will have a higher demand for labour the lower the real wage. This is shown in Figure 1.1 in which the quantity of labour (N) is plotted against the real wage (w), and the demand for labour is represented as a downward sloping curve DD. Similarly it is assumed that households will be willing to supply more labour the higher the real wage, and this can be represented as an upward sloping curve SS.4 The intersection of these two curves (at E) determines the equilibrium levels of employment (Ne) and the real wage (we), for at this point neither businesses nor households will wish to change their behaviour. Alternatively, if the level of the real wage were wa, above we, businesses would want to employ only Nd workers whereas households would want to offer employment of Ns. The intentions of business and households would diverge, and at this wage there would be an excess supply of labour, equal to (Ns – Nd). Equilibrium in the labour market can obtain provided the real wage is flexible and able to fall from wa to we. At this point, because all those who wish to work at the equilibrium real wage have work, there is by definition full employment (according to the model)

Figure 1.1 Labour market equilibrium in classical economic theory.

Another cornerstone of the classical theory, which originated with philosophers John Locke (1632–1704) and David Hume (1711–1776), was the quantity theory of money. The money value of the output of the economy is equal to the physical output multiplied by the general price level. People will wish to hold money balances, mainly for transactions purposes, in proportion to this money value. Or, to put it another way, the demand for money balances is proportional to the money value of total output of the economy. At equilibrium therefore, the demand for money balances will be equal to the supply of money provided by the monetary authority. As total real output is fixed at the full employment level according to Say’s Law, changes in the money supply bring about proportionate changes in price level, including the ‘prices’ represented by money wages and the nominal interest rate. On the other hand, real prices, wages and interest rates will remain unchanged because all the money variables, including the money supply, have changed in proportion. This proposition, according to which monetary changes affect only monetary variables, and that real changes affect only real variables was a central tenet of classical theory. Money, as the classicists would say, was ‘neutral’.

So in summary it may be said that the classical model of the macroeconomy depended on three propositions: the flexibility of market processes, the working of Say’s Law which equated demand and supply and which ensured that full employment was always achieved, and inflation as a purely monetary phenomenon dependent on the quantity of money in circulation relative to the level of full employment output.5

A central problem that confronted economists in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was how long-term economic growth and prosperity could be achieved, and what would determine the distribution of the product of the economy between the three factors of production: land that received rent, labour that received wages, and capital that received profits. In particular Thomas Malthus (1766–1834), clergyman and scholar, was not optimistic about the future of society, particularly due to the effects of population increase, declaring:

Must it not then be acknowledged by an attentive examiner of the histories of mankind, that in every age and in every state in which man has existed, or does now exist; that the increase in population is necessarily limited by the means of subsistence; that population does invariably increase when the means of subsistence increase; and that the superior power of population is repressed, and the actual population kept equal to the means of subsistence by misery and vice.

(Malthus 1986: i, 139/41)

Economist David Ricardo (1772–1823) accepted the Malthusian view of population, and constructed an economic model that predicted that economic growth would eventually come to an end because of the scarcity of raw materials. As population increased, agricultural production would be forced onto less and less fertile land. The law of diminishing returns would operate so that the output per worker would eventually decline. On superior land, payment of the subsistence wage and rents allows profits as a residual. However, as less fertile land was brought into production, profits would eventually decline to zero, and capital accumulation – paid for from profits – would cease. As the rate of growth of output was held to be a function of the rate of profit on capital, economic growth too would come to an end. The solution to this problem according to Ricardo was, at least in the short run, to import cheap foreign food grains. He therefore argued against the Corn Laws and advocated free trade with other countries, based on his theory of comparative costs.6

Ricardo’s economic theory exercised considerable influence during the midnineteenth century, and was supported by John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) among others. However, enthusiasm for the approach began to wane as expansion of the extensive margin of land was augmented by colonial settlements overseas, and improvements in technology (and later, birth control) undermined the rationale for claiming that increasing population and resource scarcity would lead to declining capital accumulation and reduced economic growth. Malthusian and Ricardian concerns for population and resource scarcity were effectively banished from their central place in economic theory with the coming of the socalled ‘marginalist revolution’ in economics late in the nineteenth century. However, as we shall see in later chapters, Malthusian concerns have not lost their relevance.

The marginalist revolution: neoclassical economics

Whereas the major concerns of the classical economists were for economic growth and the aggregate aspects of the economy – what we today would call the macroeconomy – nineteenth century economists also struggled with microeconomic concerns such as how to explain the value that individuals attached to specific goods and services. Smith, and after him Ricardo and Mill, held that the value of a good was related to the amount of labour enshrined in its production. Thus the reason for the high cost of diamonds relative to water was because of the greater labour required to find and extract the diamonds. However, a more persuasive explanation was provided by the Frenchman Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot, a contemporary of Adam Smith, who proposed that value was subjective, reflective of individual desire, and would change according to need rather than being consequent on anything so objective as labour content.

In the latter part of the nineteenth century, economists (and in particular the Frenchman Leon Walras, Englishman William Jevons and Austrian Carl Menger) explored the ways in which factors of production could be optimally allocated in an economy. They were able to draw together the three strands of Smith’s belief in the operation of markets and the invisible hand, Turgot’s subjective theory of value, and Jeremy Bentham’s utilitarianism as the appropriate ethical standard for society (see following chapters), into a mathematical description that employed the differential calculus and its ‘marginal’ properties. Also introduced was the important idea of ‘opportunity cost’, namely that the economic cost of an action is equal to the value attached to the foregone alternative. This is now a fundamental concept for economics in a world in which resources are scare and have alternative uses.

On the side of consumption, the value of a good (or service) to an individual was now seen as the benefit, or utility, derived from the next additional unit, i.e. the utility provided by the good at the margin. This proposition was referred to as the ‘marginal utility theory of value’. The so-called ‘law of diminishing marginal utility’ expressed the idea that, for any individual, each additional unit of a good provided less subjective value than the preceding one.7 On the side of production, the ‘theory of marginal productivity’ held that the reward received by any factor of production contributing to the productive process would be equal to the reduction in output due to the withdrawal of one unit of that factor (with the level of other factors remaining constant). And also on the side of production the law of diminishing returns, originally expressed by Ricardo in relation to agricultural land, was generalized to become the ‘law of diminishing marginal productivity’ and applied to each of the factors of production, namely the input to a productive process of additional units of any one factor (with other factors held constant) would, beyond a certain point, yield progressively smaller increases in output. A further consequence of employing the differential calculus was the ability of economists to operationalize ideas of maximization and minimization. Consumers, the theory held, would maximize their utility subject to the constraint of their income, and businesses would maximize their profits subject to the constraint of their costs. Thus the calculus provided a powerful means of investigating the determinants of supply and demand in markets as consequences of utility and profit maximization.

The combination of the ideas of market supply and demand and equilibrium derived from the classics, with these nineteenth century ideas of methodological individualism, marginal utility, marginal productivity, and the notion of maximizing behaviour, became known as ‘neoclassical economics’, and provided the foundational principles for economic orthodoxy for much of the twentieth century.

The Keynesian ‘revolution’

The stock market crash of October 1929 heralded the economic slide into the Great Depression; at that time the deepest economic slump in the history of the Western industrialized nations. Its most severe effects lasted from 1929 until 1932, although these were not fully dissipated until the coming of the Second World War. The Depression severely affected many countries, most particularly the USA, those in Western Europe, Canada, and Australia, although few if any countries escaped its influence entirely.

Between 1929 and 1932, industrial production in the USA fell by 45 per cent, GDP contracted by 28 per cent, unemployment rose from 3 to 22 per cent of the workforce, and more than 5,000 local and regional banks closed their doors (Maddison 1982). With this huge contraction in economic activity, imports to the US shrank significantly, and as the flow of credit to debtor countries dried up the effects of the downturn were rapidly transmitted around the world. Export-oriented countries were particularly hard hit. Many countries attempted to introduce protective measures such as tariffs to restrict imports, and competitive currency devaluations. But such beggar-thy-neighbour policies merely exacerbated the deflationary spiral of prices and wages and the depth of the crisis. The collapse of banks in the USA and Europe put increasing pressure on the Bank of England as a source of credit, and combined with massive withdrawals and its own precarious financial position, the Bank was forced to abandon the gold standard in September 1931, and the pound allowed to depreciate against other currencies. The psychological repercussions of the abandonment of the gold standard on world economies was immense, and prefigured the demise of the international monetary mechanism which had been rebuilt following the First World War (Aldcroft 1986).

Whatever the causes of this painful global downturn, most contemporary economists’ policy prescriptions, at least at the theoretical level, were based on Say’s Law: namely that given time, the self-adjusting powers of the market would work themselves through the system, and wages and pric...