- 372 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Papua New Guinea is the first book to explore the economic development of this socially complex, rapidly changing nation. Subjects discussed include:

* rapid economic growth and political conflict

* civil war on the island of Bougainville

* population growth and urbanisation

* mining: gold, copper and environmental conflicts

* uneven development and social divisions.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Introduction

Papua New Guinea in the international economy

Until very recently indeed, as anthropologist Fredrik Barth has written, a man of the mountains could squat on his verandah, and see smoke rising in the forest three days’ walk, 30 miles away, and know that no person he had ever met had visited such a place, or any place beyond it, or knew anything about the people lighting these fires.

(Jackson 1982a:18)

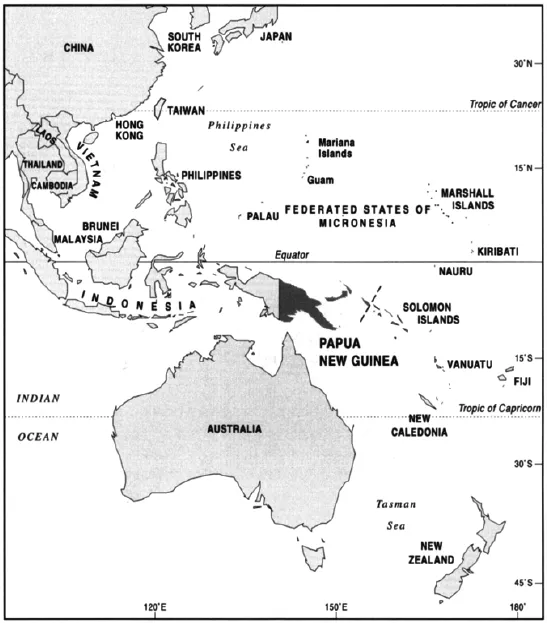

No country in the world offers the stunning diversity and contrasts of Papua New Guinea (PNG), a country typified by the extent of social differentiation across even very small areas, with more than eight hundred languages, some spoken by fewer than a hundred individuals, and by such late and limited contact with global economy and society that cultural distinctions retain extraordinary vitality. PNG consists of the eastern half of the island of New Guinea plus many islands to the east, the largest of which are New Britain, New Ireland and Bougainville, with a total land area of about 465,000 square kilometres and a population of over 4 million. The ‘last’ parts of PNG were probably not ‘contacted’ until the 1970s— as the country became independent—in the final flurry of world exploration, yet it has become intrinsically part of a world economy. Whilst conventionally regarded as a South Pacific island state, it dwarfs other island states in every way. It shares a long land border with Indonesia (Irian Jaya), has observer status in the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) and diplomatic, aid and commercial ties of growing importance with Asia. As Australia’s only former colony it maintains a ‘special relationship’ with its southern neighbour, though this relationship became more difficult and complex in the post-colonial era after 1975.

PNG belatedly and briefly experienced rapid economic growth during the 1990s. The real growth of the nation’s gross national product (GNP) in 1993, at 16 per cent, was the highest in the nation’s history and one of the highest in the world. This followed the first full year of oil production at the new Kutubu field, the increased value of log exports and slight growth in the agricultural sector; oil and gold dominated exports in a country still widely perceived as characterised by subsistence agriculture. Within PNG the mineral resources sector is viewed as the critical engine of growth, and a means of reducing aid dependency. Consequently the agricultural sector has lagged, as the focus of change has moved from distribution to growth.

Figure 1.1 The Asia-Pacific region

Global culture and society have arrived. Satellite dishes import Indonesian and Australian television channels; rugby league is the male national sport. Teeshirts, jeans, sunglasses and digital watches are prominent in the towns, where university graduates distance themselves from rural folk, and are often perceived as susokmen (shoe and sock wearers), unlike barefooted or thongwearing villagers. An elite choose to shield themselves behind the darkened windscreens of air-conditioned cars, sure targets for the gang raskals (criminals), envious of such isolation and conspicuous consumption. There is juxtaposition of corporate monoliths and plywood shacks, of affluence and poverty, of modernity and tradition. New lingua francas are crucial, and the principal one, Tok Pisin, accommodates such new constructs as ekwiti (equity) and hansapim (stick-up), different responses to economic change. In one glossary sanguma (sorcery, magic) is neatly juxtaposed with sekonhan klos (Tree 1996). On Bougainville, where the army seeks to overcome secessionist rebels, babies have been named Heli and Soe—the first born to a family forcibly relocated by helicopter (part of Australia’s military aid), and the second born during a State of Emergency. In the capital, a migrant worker, Pepsi Cola Gabi, was jailed for murder in 1991 whilst in remote parts of the highlands, the last stone tools had only just been produced. A year later the Vanimo district court in West Sepik jailed two men for practising sorcery whilst national politicians began moves to establish the country’s first stock-exchange.

Travelogues on PNG continue to emphasise such themes as ‘unchanged over time’ and ‘Stone Age society’. In 1962 a National Geographic editorial informed its readers:

At a time when astronauts have orbited the earth and scientists plan conquests of the planets, one corner of the world still competes with space for men’s imagination…. Here, on an island flung across the tropical Pacific like a grotesque 1500-mile long bird, are mountain valleys and jungle pockets that await their first explorer. Here live people who never saw a wheel until it dropped to them from the skies on an airplane.

Seven years later, in an article entitled ‘Journey into Stone Age New Guinea’, the author recorded ‘islands of Stone Age life still uneroded by currents of change’ (Kirk 1969:568); although that phrase captioned a photograph of a Melanesian wearing shorts, and steel axes and airstrips were discussed, the principal themes were remoteness, traditional medicines and cannibalism. It was just six years before independence. A few years later Carleton Gajdusek received the Nobel Prize for research on the links between virus transmission, cannibalism and a fatal disease (kuru) in the Eastern Highlands. In such ways no country has been seen as more exotic: a place of exhibition, curiosity and spectacle, existing in supposed timelessness. The rapidity of change since the early 1970s has shown that there are other very different realities.

A HISTORY OF DIVERSITY

PNG has an extremely lengthy history of human occupancy, following the migration of Melanesians from the west. Radiocarbon dates have established settlement at more than 40,000 years ago. Permanent agriculture and water control techniques in highland valleys date back at least 10,000 years. Large areas of PNG were unknown to the world beyond until well after the Second World War. Not until the 1920s was exploration of the interior combined with the search for gold; in the 1930s, expeditions crossed into the highland valleys contacting large numbers of people whose presence had not even been suspected. In the post-war years administration patrols travelled into still uncontacted areas; administration reached some interior areas only in the late 1960s. During the 1980 census a handful of villages were enumerated for the first time, and others have since been ‘discovered’.

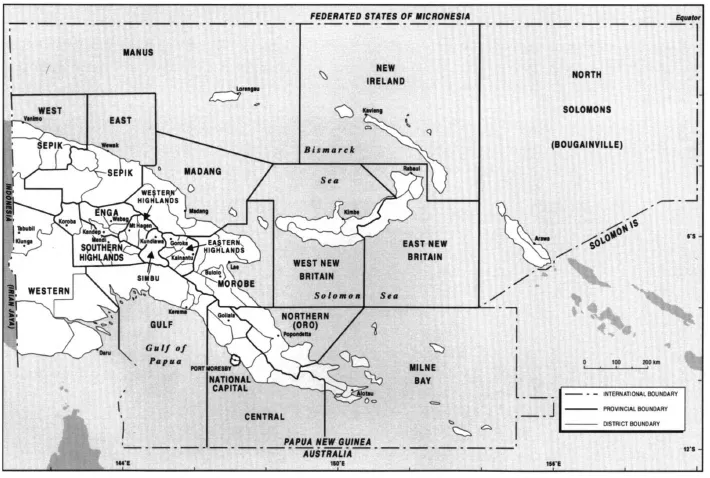

The mainland is extremely rugged with mountain ranges reaching over 4,000 metres. Other islands are mountainous microcosms of New Guinea itself. Transport infrastructure is limited; no road links the capital, Port Moresby, and the second largest city, Lae. Many active volcanoes have caused deaths and forced population migration. North and south of the main dividing ranges are vast swampy areas around the Purari and Fly rivers in the south and the Sepik river to the north (see Figures 1.2 and 2.1). Within the massive central cordillera lie valley basins, all more than 1,000 metres above sea-level, that are the most densely populated part of the country.

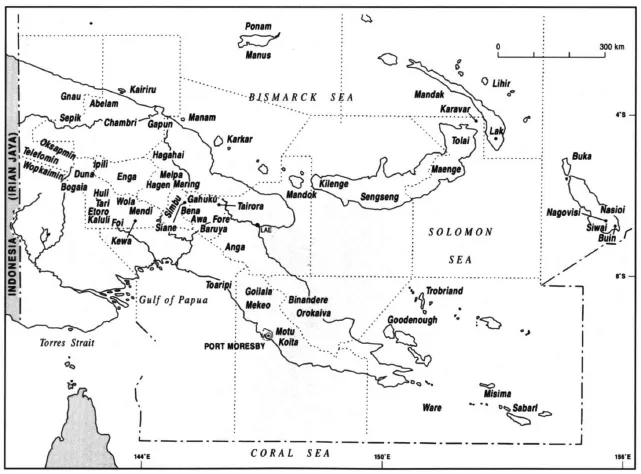

Despite an enormous variety of cultures in PNG, almost all the indigenous population in pre-contact times was Melanesian, apart from the tiny Polynesian outlier populations on the northern atolls of Bougainville. Linguistic diversity has given rise to lingua francas: Motu in the Papuan region around Port Moresby and Tok Pisin (Pidgin English) throughout the rest of the country. English however is the language of education, government and commerce. The social systems of the various cultural groups differ; patrilineal descent systems predominate in large areas of the highlands and matrilineal systems in the eastern islands. Leadership, exchange systems, rituals and ideologies vary substantially. A massive difference exists between coastal areas, with more than a century of culture contact, and more isolated inland groups which have experienced minimal acculturation and have little concept of any national identity. Post-contact transformation has at certain times and in particular places been so rapid that structural changes which elsewhere evolved gradually over many generations have been telescoped into a few decades (Howlett 1980). PNG populations have retained many smallscale and distinctive social and economic systems, with limited division of labour (other than by gender). National unity is restricted by linguistic and cultural diversity, regional divisions, especially between the highlands and the Papuan coast, and the recency of colonisation and decolonisation.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century planters and missionaries from Germany, Britain and Australia had established mission settlements and plantations on the coasts and islands; traders and labour recruiters moved these frontiers inland but it was not until after the Second World War, and in parts of the more remote highland regions much later, that the social and economic institutions of colonialism—taxation, wage labour, cash cropping, missions, local government councils, health and education systems—were established throughout the country. Britain claimed Papua—the southern half of the mainland —in 1884, whilst Germany simultaneously established authority over parts of New Guinea. Following the First World War, Papua and New Guinea were administered by Australia (the latter under mandate from the League of Nations). After the Second World War, the two administrations were combined, and the country moved towards self-government in 1973 and independence in September 1975. The possibility of decolonisation in PNG was an eventuality that Australian administrations were generally content to ignore until well into the 1960s. Indeed PNG was one of the last places in the world where white settler colonialism was advocated as colonial policy (Ward and Ballard 1976:440). Independence largely failed to generate a spirit of national development. Secessionist movements, especially on Bougainville, have posed grave and still unresolved problems about national unity. Australia played the most crucial role in the colony, a special relationship shaped by colonial economic structures (especially in commerce), new economic relationships in the mining industry, assimilationist assumptions in policy and administration, and in post-colonial times by investment and economic aid. All this was heightened by the proximity of the two countries. In the Torres Strait Australia and Papua New Guinea were barely a kilometre apart (Figure 1.3). Geography contributed to the maintenance of many colonial ties. The legacy of colonialism was the continued—and seemingly inescapable—significance of Australia for national development.

Although European contact has been extremely recent, the rapidity of change before or after contact was sometimes exceptional. Customs sometimes disappeared surprisingly quickly; the Fore of the Eastern Highlands gave up fighting when the first administration officer appeared, ‘almost as if they had only been awaiting an excuse to give it up…. They looked to his arrival as the beginning of a new era’ (Sorensen 1972:362). More generally the recognition that the new arrivals were to be a permanent feature of their lives often provoked a crisis (Rowley 1965). The veneer of colonialism was relatively light, but its impact was uneven, though the tentacles of overseas commerce reached out to every part of the country. In the two decades since independence, change in PNG has been extremely rapid as the economy has moved from its historic orientation to agriculture towards mineral production and export. For much of the 1970s and 1980s there was steady economic growth, as both sectors developed, but in the past few years there have been severe challenges to this. The most dramatic of these has been the closure of the Panguna gold and copper mine in Bougainville, and the isolation of Bougainville from PNG; this led to a sudden drop in gold and copper exports, a less precipitate but still significant loss of agricultural exports, civil war conditions, resulting in many deaths and much misery, the return of migrant workers from Bougainville to rural and urban areas where population was already growing rapidly, and a consequent disinvestment in the public sector. World commodity prices have largely continued their recent decline. The population has continued to grow extremely quickly, at an average rate of perhaps 2.3 per cent since the 1980s, increasing demands on inadequate services and leading to considerable population pressure on resources in localised areas. Urban facilities have been particularly strained, and squatter settlements, despite local hostility, have steadily grown as a result of immigration in response to growing perceptions of deprivation and uneven development. Urban unemployment is increasingly visible, hence the emergence of crime, violence and raskal gangs. After two decades, the optimism that coincided with independence largely disappeared, whilst corruption in the chase for privileges, perks and power has emerged. The police and the army, divided amongst and between themselves, have been unable to challenge corruption, crime or the separatist tendencies of remote regions. With a relative and newfound abundance of natural resources (especially minerals), a low population density, and an independence date later than in most other parts of the world, PNG had opportunities for economic choice and change that were rarely present elsewhere. Yet, in the end, late development tended to reproduce colonial conditions rather than produce a distinctive economic and political structure.

Figure 1.2 Papua New Guinea provinces

Figure 1.3 Cultural groups and culture areas

The integration of economic growth and social development has been difficult, there has been little concern for environmental degradation and women have been excluded and marginalised by development trends. Despite fundamental problems, macro-economic management has been effective, the country remains a parliamentary democracy, though militarisation has increased and human rights have decreased. Tribal tensions have irregularly appeared, especially in the highlands, whilst on Bougainville a civil war has lasted more than six years. Early constraints to development—the lack of a unifying infrastructure, rugged terrain and a widely dispersed, poorly educated and culturally diverse population—have been compounded by administrative fragmentation, complexities of land tenure, global commodity price fluctuations, rising expectations and increasing populations. Parts of the country are without roads, telephones, electricity, adequate water supplies or access to health and education services. Until quite recently almost everybody in Papua New Guinea was more familiar with sorcery, spirits, reciprocal violence, gift exchange, subsistence agriculture and local languages than ‘such bedrock institutions of the economically developed world…as money, buying and selling, employers and employees, wages, salaries, and the calendars and clocks used to measure time and organise labour’ (M.F.Smith 1994). Not surprisingly, moving between such different worlds—physically and metaphorically—has posed problems, created tensions and made development elusive.

2

The constraints of late development

Petroleum may be regarded as the pearl shell of industrial civilisation. The avarice it evokes, the ruthlessness with which government bureaucrats and multinational corporations compete over it, and the political forces, rivalries and skulduggery that are called into play in the process are the modern versions of life in the Waga and Nembi Valleys [Southern Highlands] in the late 1930s. These corporate struggles carried on from lofty glass buildings, plotted with the aid of computers, organised through satellite links, and fought by warriors who arrive on executive-class flights—all take place beyond the peripheries of the people who inhabit the regions concerned. The direction of their future will be decided in deals struck between bureaucrats in Port Moresby and executives in London, Sydney and New York, by people they don’t know about and will never see. It might as well be the spirit world.

(Schieffelin and Crittenden 1991:282)

THE ENVIRONMENTAL STAGE

More than a hundred populated and unpopulated islands make up PNG. These islands contain an extraordinary variety of landforms, ranging from massive cloud-shrouded mountains, vast lowland swamps, atolls and reefs that barely rise above sea-level and marine chasms of considerable depth. In the jungles the diversity of flora and fauna ranks with that of any other part of the world. Volcanoes regularly threaten life, in Rabaul and elsewhere. Though the climate is tropical, except at the very highest altitudes, extremes of drought and flood, and more rarely cyclones and tidal waves in coastal areas and landslides and frosts in the highlands, pose intermittent problems.

New Guinea, the world’s largest island after Greenland, has a central cordillera that stretches 2,400 kilometres from the west of Irian Jaya to the Coral Sea and the archipelagoes of Milne Bay Province. Mt Wilhelm rises to nearly 4, 500 metres; around this and other mountain peaks the barren landscape is clearly of glacial origin. On the outlying islands the pattern is similar but on a smaller scale. Landforms are steep and human settlement is extremely restricted. Massive peaks, deep gorges, turbulent rivers and enclosed valleys are specific to the island of New Guinea but the isolation and remoteness imposed by stark mountain ranges are now often little different from that of many of the smaller islands (Figure 2.1).

Sheer mountain ranges, vulcanicity and earthquakes characterise relatively recent land formation. The ranges are composed of igneous, sedimentary and metamorphic rocks, on which many soil types have evolved, that contain minerals, many of great commercial importance. The boundary of the Pacific has become the rim or ‘ring of fire’ that runs in a broad arc th...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Tables

- Notes and abbreviations

- Preface

- 1: Introduction

- 2: The constraints of late development

- 3: Subsistence and survival

- 4: An agricultural economy?

- 5: Fish, forests and sustainable development

- 6: Mining

- 7: Mobile Melanesians?

- 8: Urbanisation, urban life and the urban economy

- 9: Uneven development

- 10: The political economy of development

- 11: Conclusion

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Papua New Guinea by John Connell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Economic Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.