![]()

Part I

Overview

![]()

1 The Global Financial Crisis

An unprecedented configuration for monetary policy

Introduction

In 2008–2009, the world experienced ‘by far the deepest global recession since the Great Depression’ (IMF, 2009). Regardless of the existence of varying policy objectives assigned to central banks, it is a truism, five years after the beginning of the crisis, to state that significant limitations have been imposed upon monetary policy. The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) has undoubtedly shaken the world of central bankers and taken monetary policy into unchartered territory. This overview announces the structure of the volume. In the first part of the book, we will examine the mantras of the 1990s embedded in the NMC, before examining, in a second part, how monetary policy has been transformed in the aftermath of the GFC.

The Global Financial Crisis: what future for monetary policy?

The subprime crisis broke out in August 2007. One year later, following the demise of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, the crisis mutated into the first global crisis of the twenty-first century, the latter episode of which being the enduring Euro sovereign debt crisis. The aim of this book is to assess whether the subsequent cataclysmic chain of events has shaken the New Monetary Consensus. It is indeed difficult to convey how much doubt has been thrown on the entire corpus of central banking theory by the current global crisis. Macroeconomic indicators have become unpredictable, rare (so-called black swan) events have become common and accepted orthodox frameworks have lost their appeal.

Stated objectives

Following an overview of the situation, we depict the evolution of central banking practices over the last half century, with the underlying theoretical frameworks and the corresponding macroeconomic outcomes. We then thoroughly analyse the mantras of the 1990s, leading to a worldwide configuration for monetary policy up until 2007. In the aftermath of the worst crisis since the Great Depression, we scrutinize the unconventional responses of central banks, and we sketch out the nature of future monetary policy by addressing the following questions: Is the Taylor rule still a satisfactory precept for central bankers? Has the crisis irreversibly tarnished the NMC? What are the fundamental issues raised by this cataclysmic chain of events? How much reliance should we put on formal models? How should central banks conceptualize monetary policy anew in a post-crisis scenario?

Structure of the volume and methodological considerations

An extensive literature existed on the NMC (under the inflation targeting umbrella term) prior to the crisis. The claimed novelties of this book are twofold. Because we begin this volume with a historical overview, it therefore becomes natural to view the NMC as a historical moment in a long-term perspective à la Braudel. Therefore, this first part (which could not have been written before the crisis) must be read through the lenses of the economist and the historian. Chapter 1 begins with a brief overview and a statement of objectives. Chapter 2 contains a brief introduction to monetary policy spanning over several decades until the inception of the NMC. Chapter 3 is didactical in essence, and presents a simple three-equation model of the NMC in closed-economy analysis. A slightly more complex six-equation model is sketched out for an open economy. The following chapters offer a rigorous and critical analysis of the NMC mantras, understood as catchwords with an axiomatic dimension, namely transparency (Chapter 4), credibility (Chapter 5), price stability (Chapter 6), interest rate rules (Chapter 7) and finally inflation targeting (Chapter 8).

Although the first part of the volume proposes a seemingly diachronic analysis of the NMC during its existence, no deliberate attempt is made to undermine the NMC from the onset in synchronic terms. This would be way premature. However, in the first part, the reader, almost imperceptibly comes across brief reflections that start to shed light on the NMC in a critical post-crisis (and historical) perspective.1 We prefer to talk about rather dim, and not dazzling, light here. The second part is less ambiguous, as it investigates a straightforward question. Does the GFC constitute the end of an era for monetary policy and, if so, in what sense? Chapter 9 focuses on the statutory missions of the Fed and the ECB; the impact of the GFC on these two institutions is apprehended through the lenses of the ‘new normal’. Further limitations of the NMC are examined in the light of the problematic issue of the US dollar. Chapter 10 examines issues of exchange rate movements and international monetary coordination in a post-crisis scenario. The unavoidable problem of the zero bound on nominal interest rates is discussed in Chapter 11. Chapter 12 is a rather original end personal essay on the austerity versus growth conundrum that aims to depart sharply from commonly held views in mainstream economics. Chapter 13 looks at the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing programmes, by examining their nature, their scope and their effectiveness. It is argued that these unconventional monetary policy measures do not fit well into the NMC apparatus. Chapter 14 aims to single out the learning lessons for the contemporary period, derived from the theory of optimal currency areas developed by Robert Mundell more than fifty years ago. Chapter 15 focuses on the Euro sovereign debt crisis for which, we argue, the NMC has little, if nothing, to say. Chapter 16 concludes this volume, by broadening the reflection to post-crisis methodological considerations in central banking theory.

In this book, we have decided to devote little space to the narrative of the GFC, which has been extensively covered elsewhere. Instead, we shall focus on the transformative paradigmatic dimension of the GFC as regards the NMC. We will eventually let the readers decide, whether or not our conclusion phrased at the end of the book is warranted, both for the economist and the economic historian.

![]()

Part II

The new mantras of the 1990s

![]()

2 Introduction

Monetary policy prior to the NMC

Introduction

In this chapter, four historical Moments are singled out in the post-war period, to help put the emergence of the NMC into perspective. After briefly describing the ineffectiveness of monetary policy throughout the 1950 and 1960s, we look into the 1970s, a chaotic decade in which monetary policy was temporarily defeated by the inflation spectre. Then, we discuss the monetarist experiment, with a focus on the UK. Finally, we present the transitional period towards the NMC with the pioneering inflation-targeting experiment conducted in New Zealand from 1989 onwards. The pivotal role of the Maastricht treaty and the influence of supply-side economics on the birth of the NMC are discussed, before finally phrasing the theme of the book.

Monetary policy ineffectiveness in the 1950s and 1960s

The interdependence of policy objectives

The post-war period was characterized by a policy mix endorsing the interdependence of policy objectives in which inflation was interwoven with employment, the balance of payments and economic growth (Greenaway and Shaw, 1988, p. 379). However, this interdependence of objectives would soon come in contradistinction with the Tinbergen rule that we will briefly evoke.

The stop and go policies

Prior to the late 1970s, monetary policy was encapsulated in a surprisingly reductive dialectic between unemployment and inflation, notably symbolized by the stop–go policies and the Phillips curve. The economy was stimulated by low interest rates in the go phase, until overheating inevitably gave rise to inflationary pressures, and triggered the stop phase characterized by a restrictive monetary stance. The business cycle was narrowed down to its simplest form, and the resulting policy response was made entirely predictable for economic agents.

The Phillips curve

Charles Bean (2007) has provided an interesting historical overview of the past half century. He begins his survey with Phillips’ pioneering work (1958), written at a time when policy makers believed that there existed an exploitable inverse trade-off between unemployment and inflation. It was believed at the time that the government was able to lower unemployment, in case it was willing to tolerate higher inflation. If excess demand pressures showed signs of spilling over into excessive inflation and a deteriorating balance of payments, a restrictive fiscal policy was the chosen tool, in order to mitigate inflationary pressures.

The non-compliance with the Tinbergen rule

Tinbergen (1952) argued that the number of policy objectives should not exceed the number of instruments.1 Each instrument should therefore be assigned to the objective upon which it has the greatest impact. The Tinbergen approach exercised considerable influence upon policy discussion during the 1970s, and later became the favoured approach of policy makers. Before making its way in policy circles, the Tinbergen rule was repeatedly violated throughout the 1950s and the 1960s. Policy makers believed at the time that fiscal policy could simultaneously target low unemployment and achieve price stability.

The primacy of fiscal policy

Fiscal policy is one of the tools of economic policy. It affects the level, composition or timing of government expenditures, and can modify the burden, structure or frequency of taxation. Fiscal policy matters in the sense that it needs to be commensurate with macroeconomic expenditure flows. Fiscal policy alters aggregate output, whether directly (through the Keynesian multiplier effect) or indirectly through tax and transfer changes. Bean (2007) argues that fiscal policy was the primary macroeconomic stabilization tool in the post-war period. Greenaway and Shaw (1988, p. 381) aimed to explain the downgrading of UK monetary policy during this period. They argue that British economists were paying inordinate amount of attention to Keynes’s special cases, such as the liquidity trap and interest inelastic investment (ibid.). Greenaway and Shaw (ibid.) also emphasize the Radcliffe Report (1959), which undermined the effectiveness of monetary policy in achieving short-term demand management.

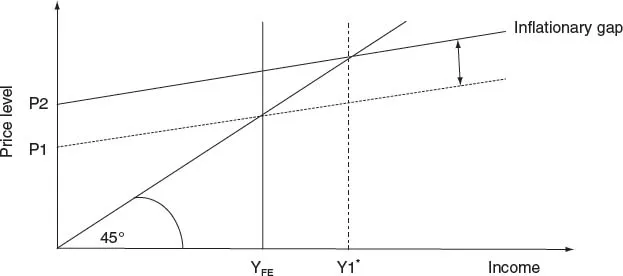

The IS/LM framework and the inflationary gap

In the IS/LM construct, the inflationary gap denotes an abnormal discrepancy between equilibrium aggregate production and full-employment aggregate production, when the former is greater than the latter.

An inflationary gap arises when the economy has been expanding on the back of a high level of aggregate demand. Total spending and the economy’s ability to supply goods and services no longer move in concert, the former outpacing the latter. As a consequence, actual GDP exceeds potential GDP. Interestingly enough, the inflationary gap, couched in modern language, is the alter ego of the output gap:2 ‘just as today, the conventional view of inflation was that it was caused by an excess of aggregate demand at or near the “full employment” level of output’ (Thornton, 2010, p. 91). The inflationary gap is combatted by a restrictive fiscal policy (higher taxation) or monetary policy (higher interest rates), through its impact on aggregate spending.

Figure 2.1 The inflationary gap on a Keynesian 45 degree line diagram.

Demand management manipulation

Supply-side economists sometimes argue that productivity gains and enhanced efficiency lead to a rise in aggregate supply, thereby reducing the amount of excess demand in the long run. In theory, inflation control can thus be achieved by supply-side policies. However, the prevailing orthodoxy between the early 1950s and the mid 1970s, was in the Keynesian tradition of demand management manipulation as a determinant of inflationary control (Greenaway and Shaw, 1988, Ch. 18). Whether monetary policy affects the economy through supply or demand effects is a question of utmost importance. The Monetary Policy Committee (1999) discarded the supply-side effects of monetary policy, as its impact can only be apprehended via its influence on aggregate demand. In a surprising lineage with the Keynesian orthodoxy of the 1950s and 1960s, the emphasis on demand management will become a key feature of the NMC in the 1990s. Only the policy instrument will differ.

Wage controls

Greenaway and Shaw (1988, p. 384) critically assessed the performance of the UK economy during the Keynesian years, when demand management policies were at the heart of inflation control. They argued that fine-tuning policies failed to contain inflationary pressures. More precisely, fine-tuning policies are necessarily imperfect, because they overlook the weight of wage inflation. Laidler (1997, p. 153) argues that wage and price controls became regarded as alternatives to monetary policy in the 1960s, and started to be implemented in the 1970s in the UK and the US. However, these attempts were largely unsuccessful (ibid.) in the light of the subsequent inflationary chaos. First, the implementation was deemed excessively bureaucratic and costly. Second, wage controls were criticized for generating distortions and disturbing the pattern of relative prices in the economy. Later, further works (Meade, 1985; Layard, 1986) were conducted, so as to rehabilitate wage controls, through the design of more efficient tax-based income policies, in order to achieve inflation control. These debates were never settled satisfactorily, but considerably underlined the limitations of Keynesian fine-tuning policies.

The triumph of the Monetary Policy Ineffectiveness Proposition (MPIP)

The MPIP: the orthodoxy of the 1950s and 1960s

Although we draw a parallel between the emphasis on macroeconomic demand management in the Keynesian post-war era and under the NMC, starting from the 1990s until the GFC, one major difference lies in the diametrically opposed validity given to the MPIP. The MPIP states that monetary macro-policy is of little help in achieving effective demand management. The MPIP was very much an accepted d...