1

INTRODUCTION

A successful economy is one which has at least two main features. First, its actual real output does not fluctuate much from natural real output.1 Second, its natural real output grows at a rapid, but steady pace. While the determination of the level and the rate of growth of natural real output is the focus of growth theory, the determination of actual real output relative to natural real output is the concern of stabilisation theory, and together they form the subject matter of macroeconomics. Implicit in macroeconomic theories are questions about the role of economic policies in growth and stabilisation (Branson, 1989). The two main macroeconomic instruments are fiscal policy and monetary policy. This book provides a survey of issues pertaining to the role of monetary and financial policies in growth and stabilisation in developing countries. As pointed out by Drake (1980), the earlier literature defined finance narrowly to mean only government revenue and expenditure (public finance). However, for the purpose of this survey, finance is defined broadly to include all aspects of borrowing and lending which affect the money supply.

In the literature for developed countries the role of monetary and financial policies is associated with the taming of business cycles.2 In contrast, the role of monetary and financial policies in developing countries is linked with the promotion of economic growth and development. Such a dichotomy in the role of monetary and financial policies reflects the differences in economic issues and priorities of policy-makers in developed and developing countries. Although the principal preoccupation of policy-makers in developing countries is to attain rapid growth and change in the composition of output, the concern for growth of output and structural change is not independent of the concern for price stability and external balance (Coats and Khatkhate, 1984). For example, as the experience of Latin American countries shows, if the inflationary pressure that emerges during the process of development is ignored and the inflation rate is allowed to rise rapidly, resources will be allocated inefficiently, and this will ultimately impede development. The Latin American experience also demonstrates that higher inflation rates in these countries vis-à-vis their trading partners are a major cause of the loss of their competitiveness and, hence, the worsening of their balance of payments position. The exchange rate crisis that emanates from worsening balance of payments leads to capital flight which adversely affects the growth of output. On the other hand, the overwhelming lesson from the experience of East Asian newly industrialising economies (Hong Kong, Korea, Singapore and Taiwan) and South East Asian countries (Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand) is that in the long run the growth of real income and overall monetary equilibrium, defined to include both the domestic price level and the external sector, are mutually interdependent.

Thus it can be argued that the objectives of a stable price level, the balance of payments equilibrium and economic growth are intertwined. Any demarcation in the roles of monetary and financial policies in growth (long-run) and stabilisation (short-run) in developing countries is artificial and somewhat misleading. Monetary and financial policies have both short-run and long-run roles. In the short run, monetary and financial policies should maintain such key macroeconomic variables as real interest rates, inflation rates and exchange rates at levels which will ensure the balance between aggregate demand and aggregate supply (or gross investment and gross savings). In the long run, these key macro variables must also enhance both savings and investment rates so that the economy grows at a faster rate. If monetary and financial policies fail in their short-run roles, the resulting inflation and balance of payments problems will affect the long-run objective of raising savings and investment rates adversely. Similarly, if the savings rate continues to be low, the economy will have perpetual and unsustainable external imbalance. Therefore, the essential role that monetary and financial policies can play in developing countries is to provide a stable macroeconomic environment conducive to economic growth.

TAMING BUSINESS CYCLES: THE ROLE OF MONETARY POLICY IN THE SHORT RUN

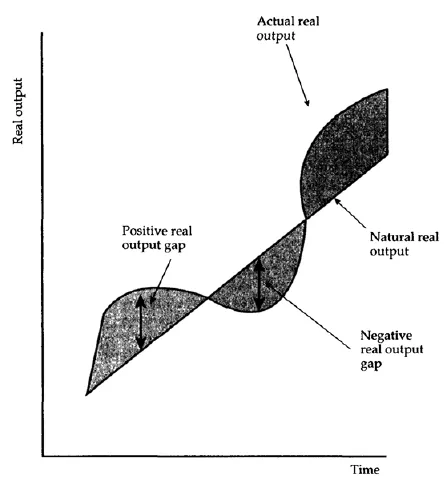

Figure 1.1 shows the hypothetical case of an economy which passes through recurrent business cycles. The smooth upward-sloping line represents the growth path of trend or natural real output. The actual real output fluctuates around the growth path of natural real output. The deviation of the actual real output from natural real output is called the real output gap. Obviously, a positive real output gap occurs during a boom, and a negative real output gap occurs during a recession. A positive (negative) real output gap also represents a condition where the rate of actual unemployment is below (above) the rate of natural unemployment.

There are many factors which may cause business cycles. In general, business cycles may originate from either the demand side or the supply side of the economy in the form of random shocks, implying that they do not have any significant effect on the trend path of the economy.3 In fact, the factors that cause business cycles can be examined with an aggregate demand (AD) and aggregate supply (AS) model.4

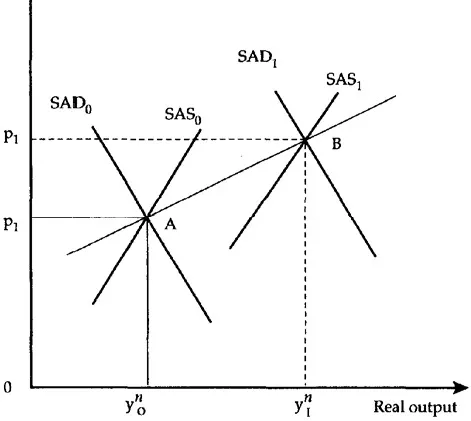

Figure 1.2 shows that at time period t0 the economy is in equilibrium at point A where aggregate demand equals aggregate supply. is the level of natural real output at the given levels of capital stock, population, and the state of technology. Any deviation of the actual real output from natural real output will arise when there is a shift in either the short-run aggregate demand curve (SAD) and/or the short-run aggregate supply curve (SAS) by economic disturbances. Business cycles represent such output fluctuations around the growth path of trend output during a time period within which long-term factors of production are assumed to remain roughly constant. In a market economy demand disturbances may originate from a number of sources, including private demand shocks, such as shifts in private consumption or investment spending, and changes in both government spending and net exports. A positive (negative) demand shock will create a positive (negative) real output gap. Like demand shocks, there can be supply shocks, such as crop failures, changes in the terms of trade, and technological innovations. A positive (negative) supply shock will create a positive (negative) real output gap. As there can be a large number of independent demand and supply shocks to an economy within a particular period of time, actual real output can be considered a normally distributed random variable with a mean equal to natural real output and a constant variance. Given that actual real output (y) equals natural real output (yn) plus transitory real output (y–yn), the mean level of real output at period to equals the level of natural real output . (That is, E(y)=E(yn)+E(y–yn)–Cov(yn, y–yn)=yn, provided that yn and (y–yn) are independent and E(y–yn)=0.) Similarly, the mean level of real output at period t1 will equal the level of natural real output . The movement of the economy from A to B during the period t0 to t1 represents the rise in natural real output as a result of the increase in each of the factors that determine the long-term growth of the economy —labour force growth, capital accumulation and technical change. Figure 1.1 Hypothetical business cycles and the output gaps

What should be done about business cycles is a subject of intense debate. When the lengths and the amplitudes of business cycles are large, they can create macroeconomic problems such as unemployment and inflation.5 As both unemployment and inflation impose economic and social costs, many economists believe that economic policies should be used to stabilise business cycles. However, what form of economic policies would achieve short-run economic stability remains a debatable issue. Because monetary policy is an important macroeconomic instrument, the debate is about whether it should be used in the same way that fiscal policy is used to stabilise business cycles. Keynesian policy activists hold the view that as monetary policy is capable of damping business cycles, it should be used along with fiscal policy for stabilisation. On the other hand, monetarist policy non-activists are not so enthusiastic about the role of monetary policy in stabilisation because they are concerned that any discretionary monetary policy may destabilise, rather than stabilise, the economy. Issues relating to stabilisation in developing countries, and in particular the role of monetary policy, are examined in Chapters 5–8.

PROMOTING ECONOMIC GROWTH: THE ROLE OF MONETARY POLICY IN THE LONG RUN

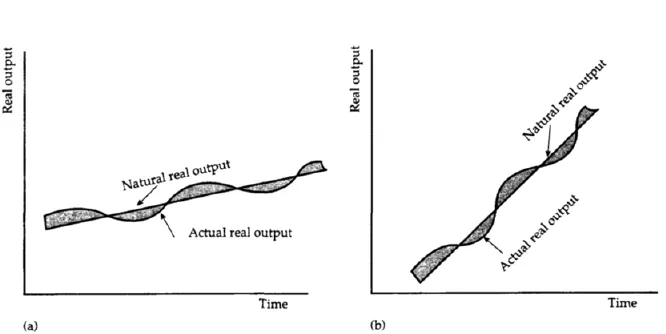

Figure 1.3 shows that an economy without business cycles does not necessarily represent a success because such an economy may be stagnant. It indicates that, given similar mild business cycles, an economy would be considered successful when it grows faster compared with an economy which grows slowly. Economic growth being a prerequisite for an improvement in the economic condition of the poor in developing countries, the natural real output must grow at a rapid and steady pace.

Figure 1.2 Movement of the real economy over time

Therefore, the predominant concern of policy-makers in developing countries is to promote economic growth, both in aggregate and per capita terms. One area of policy debate is whether monetary and financial policies can accelerate economic growth so that per capita income rises on a sustained basis. In terms of Figure 1.3, the question is whether monetary and financial policies can make the growth path of natural real output steeper and also minimise the deviations of actual output from the potential. In terms of Figure 1.2, this means maintaining a balance between aggregate demand and supply while moving from one period to another and at the same time making the time path AB flatter.

Sources of growth and monetary policy

Money’s role in enhancing the growth rate can be elaborated by Solow’s (1956, 1957) much-celebrated production function approach to growth accounting. Consider the following linearly homogeneous production function:

where y is per capita output, k is the capital-labour ratio, and T is the state of technology. Assume that the above per capita production function satisfies the standard property that the marginal product of capital is positive (δy/δk>0), which diminishes as the capital-labour ratio increases (δ2y/δk2<0).

From equation (1.1) the growth rate of per capita output (gy) can be written as

where τ is technical progress, k is the elasticity of output with respect to capital input, and gk is the growth rate of the capital—labour ratio (or capital deepening). It shows that per capita real output growth originates from two sources: technical progress and capital deepening. When there is no technical progress, the growth of per capita real output depends on the growth of the capital-labour ratio alone. Implicit in the question of whether monetary and financial policies can affect economic growth is the question of whether they can induce technical progress and/or raise capital deepening. Figure 1.3 Rate of economic growth as a measure of success (a) A slowly growing economy (b) A rapidly growing economy

The earlier literature on this area examined the role of monetary and financial policies in raising savings and capital accumulation. Although there is general agreement regarding the impact of monetary and financial policies on savings and capital deepening, the specific policy measures and the way they work remain unsettled. The works that followed Tobin’s (1965) model, and generally are Keynesian in nature, show that inflationary monetary and repressive financial policies promote growth by inducing portfolio shirts from financial assets to real capital, and/or by forced savings brought about through either transferring resources from the private to the public sector or income distribution in favour of the capitalist class. On the other hand, McKinnon (1973) and Shaw (1973) hold the view that inflationary monetary policy and financial repression retard growth as they discourage savings and financial intermediation between savers and investors, and reduce efficiency of investment. The theoretical and empirical literature pertaining to the role of monetary and financial policies in economic growth is reviewed in Chapters 2–4.

It is important to note that Solow (1957) and Nelson (1964) show that growth results predominantly from technical progress and not from the growth of either labour or capital. For example, according to Solow (ibid.), about 88 per cent of economic growth in the United States during 1909–49 could be accounted for by what he called ‘technical progress’, while the remaining 12 per cent could be explained by the increase in capital per worker. However, in Solow’s growth model, technical progress is exogenous, and there is no economic explanation of why in a free-market economy technical progress occurs. If technical progress is exogenous and plays such a dominant role in economic growth, can monetary and financial policies make any substantial contribution to economic growth? Solow’s findings imply that the contribution of monetary and fiscal policies is limited since they are aimed at raising savings and thereby the growth of capital whose contribution to output growth is small, and these policies cannot affect technical progress which is the dominant contributor to growth. Thus, Solow’s results are pessimistic about the ability of policy to change the growth path (Branson, 1989:644). If technical progress is disembodied (freely available to all), a further implication of exogenous technical progress is that the growth rates of all economies will converge over time. But it was not the case in reality (Gordon, 1993; Lucas, 1988).

Therefore, the Solow growth model has been found to be inadequate, particularly due to the restrictive assumption that technical progress is exogenous. As a result, substantial research activities have been directed towards explaining technical progress within the model itself. A new class of growth models under the name of endogenous growth theory paradigm has been recently developed in which technical progress is the outcome of market activity in response to economic incentives (Gordon, 1993; Lucas, 1988; Romer, 1986, 1990). The new endogenous growth theory considers h...