eBook - ePub

Multinational Restructuring, Internationalization and Small Economies

The Swedish Case

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Multinational Restructuring, Internationalization and Small Economies

The Swedish Case

About this book

Much of the existing literature on multinational companies has been concerned with firms originating in the world's largest economies. This book redresses the situation by presenting important information on the internationalization of a small country's industry. Multinational Restructuring, Internationalization and Small Economies goes beyond traditional studies of foreign direct investment. By using detailed data covering practically all Swedish multinationals and more than two decades of expansion in international markets, the authors describe, interpret and analyse issues which are normally difficult to investigate.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

INTRODUCTION

THE WIDER SCOPE OF INTERNATIONALIZATION

In recent decades, there has been increasing internationalization of previously national economies. While the most conspicuous change is the massive reshuffling of portfolio investment in financial markets, it may be argued that individual economies are more thoroughly affected by foreign direct investment (FDI), through which multinational companies (MNCs) own and control factors of production in foreign countries. In contrast to portfolio investment, FDI involves not only financial flows but also, in particular, transfers of intangible assets, e.g. in the form of knowledge about production processes, markets, distribution channels and management.

The significance of MNCs does not show up only through FDI, but reveals itself in a number of ways. Foreign affiliates account for sales figures which by far exceed the value of all international trade. At the same time, as much as an estimated 30 per cent of all international trade occurs within MNCs, meaning that the same organization serves as both buyer and seller. The cross-border operations of firms play a particularly important role in the international redistribution of technology. MNCs are estimated to account for some 90 per cent of all technology transfers between countries. Their role in the upgrading and spreading of skills in the work force is difficult to evaluate satisfactorily, but is nonetheless known to be paramount.

Today, the internationalization of firms’ operations affects the nature of economic activities in virtually every country, whether rich or poor, large or small. Although there have been many studies of FDI, relatively little systematic work has been concerned with MNC structures. Still, the relationship between FDI and trade, employment, technical progress, etc., crucially hinges on the organization of firms. It has therefore become essential to devote more attention to the interplay between the way MNCs are structured and the performance of economies, including policy implications concerning the shaping of economies over time.

Most work in this area has been concerned with MNCs based in the largest industrialized countries. For a number of reasons, those which originate in small countries deserve more careful study. With the domestic market relatively unimportant, for example, firms’ ability to exploit economies of scale is crucially related to the prerequisites for international trade and the internationalization of operations. Furthermore, changes in the relative attractiveness of conditions in a small home country and abroad may exert a particularly strong impact on the organization of MNCs, including that of the parent company. Linkages between specific separate firms may also be especially important in such an economy.

Going beyond the traditional flow data studies, this book describes, interprets and analyses developments associated with the expansion of MNCs based in Sweden, which is one of those countries which has been thoroughly affected by FDI. While the underlying data cover the period from 1965 to 1990, special attention is paid to the late 1980s, which have not been investigated and comprehensively summarized in previous published work. The increase in Swedish FDI during these years as well as changes in the organization of MNCs account for new patterns and consequences in notable respects.

CHANGES IN FDI

Along with the much increased volume of FDI, there have been substantial changes in the direction and composition of flows. Consider the following:

1 In the 1970s, FDI shifted away from natural resource extraction and basic manufacturing towards high value-added production, which is critically dependent on access to modern technology and a skilled labour force. In monetary terms, services—particularly related to finance—have overtaken manu facturing as the main playing field for FDI. With regard to effects on employment, knowledge creation and production capacity, however, manufacturing continues to be predominant worldwide.

2 Changes have occurred in the way foreign affiliates are established. Reliance on new ventures, so-called greenfield operations, which used to be the predominant mode of entry into foreign markets, has gradually given way to the takeover, or acquisition, of already existing firms.

3 The geographical destination of FDI has been subject to several large shifts. The United States attracted a sharply increased share of world FDI in the early 1980s, and has remained a prominent recipient since then. The integrating economies in Western Europe became a major target in the late 1980s. Although the booming East Asian region has also received an enhanced share, the developing world as a whole declined in importance during that decade. This trend was reversed in the early 1990s as flows to Asian countries expanded even further and Latin America also received increased FDI.1 Eastern Europe and parts of Africa were also the object of new interest among investors. Still, the bulk of FDI has so far been directed to the major industrialized countries.

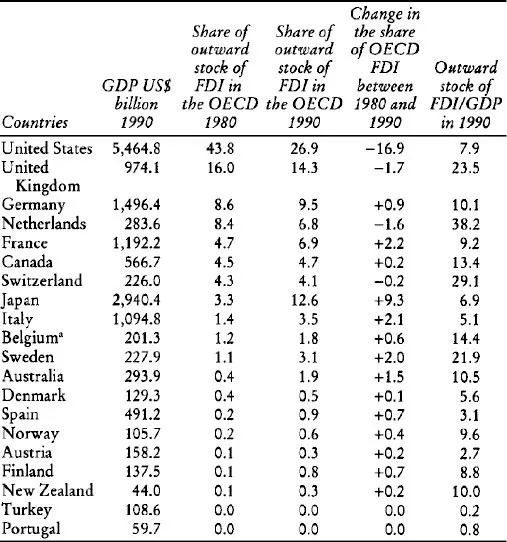

4 Finally, there has been a geographical diversification of the national origin of MNCs. The second and third columns in Table 1 show the distribution in OECD2 countries of the stock of outward FDI in 1980 and 1990 respectively. The fourth column depicts the change that occurred between these years in each country’s weight as a source of investment. The predominant reduction was recorded for the United States, which accounted for almost 44 per cent of the total stock in 1980. By the end of the decade its share had plummeted to 27 per cent. The United Kingdom, which had the second largest stock at the outset, also retreated. The most rapid growth was recorded for Japan, whose internationalization started relatively late. Most of the smaller economies in Western Europe also became more important sources of outward FDI.

The connection between MNCs and nation states has been subject to a major transformation. Gone are the days when foreign investors were simply resented as the carriers of evil. Most governments are now attempting to make their country an attractive location for MNCs. With the growing complexity of production processes and sharpened international competition, firms are focusing resources on a limited range of demanding functions and continued internationalization appears a prerequisite for the competitiveness of firms and national economies alike. Liberalization is proceeding in goods as well as factor markets, especially on a regional basis.

As the localization of production, marketing and research activities is optimized across national borders, opportunities arise for enhanced welfare worldwide. At the same time, governments as well as their constituents commonly argue that the need to offer favourable conditions to international investors limits their freedom to pursue economic policies as they once did. Monetary and fiscal policies have already been restricted by the responsiveness of financial markets. The mobility of MNCs gives rise to additional concerns with regard to tax policy, labour market institutions, social security systems and environmental legislation. The attraction of skill-intensive activities appears particularly demanding, not least owing to the importance of mutually beneficial synergetic effects and externalities in knowledge creation. Understanding the consequences and the appropriate policy response from the perspective of individual countries or regions requires a more precise picture of firm organization and the way it is changing in response to a variety of circumstances.

Table 1 Outward stock of FDI relative to GDP, 1990, and share of total outward stock of FDI in the OECD, 1980 and 1990, by country, per cent

a Including Luxembourg.

Source: OECD (1993b), UNCTAD (1994)

THE HOME COUNTRY STILL MATTERS

During most of the history of FDI, the United States has been the dominant source country. Since data on overseas operations are primarily available in the United States, it is understandable that most work on MNCs has focused on firms originating in that country. It has sometimes been argued that the national origin of MNCs is of little importance, and that such concerns are losing whatever significance they once had as firms become skilful at locating any activity where it is most efficiently executed.

Although there are partial exceptions, such as Royal Dutch Shell and ABB, the country of origin generally retains a special role for MNCs. Market share remains largest in the home country and production activities are even more concentrated there. The source of innovation, such as research and development (R&D), tends to be especially reliant on headquarters. MNCs from the United States, the United Kingdom, France and Germany typically conduct about 90 per cent of product development activities in their home country, and Japanese firms an even greater share. MNCs still prefer to appoint home country executives to head foreign subsidiaries, although a certain change has been reported in this respect (UNCTAD, 1994). Strategically important corporate functions, such as R&D and governance, consequently con tinue to draw heavily on the institutions, experience and talent of the home base.

MNCs develop and transfer assets which are unique to companies but which may still differ systematically depending on the characteristics of home countries, implying that the national origin does matter. The broadening of the geographical source of FDI, along with the prevailing focus on the United States in research on MNCs, makes it important to enlarge the scope of study to encompass MNCs based in other countries as well. The small countries which have become the origin of increased FDI, in absolute as well as relative terms, deserve special attention for several reasons.

First, the importance of internationalization for exploiting economies of scale is inversely related to the size of a country’s market. While firms based in large countries may have an advantage in enjoying economies to scale, FDI will play a more decisive role in small countries in enabling firms to cover fixed costs required for product development or marketing, for example.

Second, an appropriate understanding of and policy response to various shocks may require consideration of the productive capacity of a country’s industry which is located overseas. The foreign operations of MNCs based in small countries may weigh relatively heavily against the industrial apparatus within the national borders.

Third, large individual MNCs may play a relatively important role in small countries, e.g. in terms of trade, employment or knowledge creation. With the accumulation of skills and other intangible assets embodied in specific firms, their actions cannot be assumed to be counterbalanced by the actions of other firms. Such considerations become even more important in smaller economies, which consequently may be particularly strongly affected by the locational decisions of MNCs.

Fourth, FDI related to small countries is likely to be the most affected by regional market integration. This partly reflects the fact that the relative significance of the national market changes more in a small country when borders are removed. With the liberalization process in Western Europe, for example, there have been major alterations in the pattern of FDI both within and outside the integrating economies in the European Union (EU), previously the European Community (EC). The changes in investment have, in turn, affected the preconditions of the integration process itself.

In fact, three of the four countries which have the largest stock of outward FDI relative to the size of the economy can be said to belong to the category of small countries, given that Great Britain is regarded as medium-sized. Together with this historically leading source country, the Netherlands, Switzerland and Sweden had stocks of outward FDI exceeding 20 per cent of GDP in 1990. These countries have a high dependence on trade, a strong base of skilled labour, high R&D intensity and a history of successful innovation. For large economies such as the United States and Japan, the corresponding shares were 8 per cent and 7 per cent respectively. However, while those countries which can be expected to be the most affected by outward FDI are relatively small, there has been a tendency for inward investment to focus on the industrial core of large economies.

For such reasons, there are a number of research issues which need to be reviewed from the perspective of small countries. Because the very foundation of MNCs is associated with ownership-specific advantages, a great deal of work remains in order to settle the empirical facts. In the case of official statistics, the international operations of firms can generally be only vaguely derived from flow data regarding FDI. What matters is rather information on international operations themselves, including the structures within firms. Detailed data on MNCs’ operations in foreign countries is seldom available, and intra-firm data are almost completely lacking.

UNIQUE DATA

This study draws on a database collected since the mid 1960s by the Industrial Institute for Economic and Social Research (IUI) in Stockholm, and most recently updated to 1990. The data cover virtually the whole population of Swedish MNCs in manufacturing. Containing detailed quantitative information on activities in the source country as well as in host countries, it opens up opportunities for the study of issues which can seldom be analysed on the basis of official statistics. In fact, no other information set covers MNCs from a single country equally well in terms of either scope or detail. Nowhere else are comprehensive time-series data available on the operations and transactions of individual MNCs and affiliates.

Analyses of the IUI data up to 1986 were published by Swedenborg (1979; 1982) and Swedenborg et al. (1988), most of which are available only in Swedish. The trends previously investigated have here been updated as far as possible (see Appendix A). The speed of internationalization, changes in industrial and country characteristics, the frequency of establishments, etc., are reported so as to allow comparability over time. In some cases, results are presented for ‘identical companies’, i.e. those for which information is available from each questionnaire over a certain time period. This may, for instance, be practised when an important change in the population has been caused by major firms failing to answer specific questions.

The 1990 survey covers Swedish industrial firms with more than 50 employees and with at least one majority-owned foreign affiliate. A total of 329 MNCs responded to the questionnaire, a response rate of 94 per cent. The sample consists of 119 MNCs with and 210 MNCs without manufacturing affiliates abroad. The book focuses on the activities of the former, which have contributed information for the group of companies as a whole as well as for each individual affiliate producing abroad.3

Table 2 reports figures for the 119 company groups which have completed the full 1990 IUI questionnaire.4 Together, these MNCs encompassed 713 majority-owned foreign manufacturing affiliates. Compared with the survey which was conducted in 1986, this corresponds to a net increase of 11 MNC...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- About the authors

- Foreword

- 1 INTRODUCTION

- 2 MULTINATIONAL COMPANIES AND NATION STATES

- 3 SWEDEN AND THE INTERNATIONALIZATION PROCESS

- 4 MULTINATIONAL COMPANIES AND TRADE

- 5 TECHNOLOGY AND MULTINATIONALS

- 6 EUROPEAN INTEGRATION AND RESTRUCTURING BY MULTINATIONALS

- 7 SUMMARY AND CONCLUDING REMARKS

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

- Notes

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Multinational Restructuring, Internationalization and Small Economies by Thomas Andersson,Torbjorn Fredriksson,Roger Svensson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.