Introduction

When Frank Ramsey asked his famous question “How much should a nation save?” he faced a huge, fascinating challenge: molding for society both the present and the future of its economy in an optimal way. With his essay “A mathematical theory of saving,” he founded nothing less than the theory of optimal economic growth. However, as soon as he tried to add numbers to his theoretical results, he was dumbfounded: he obtained an “optimal” savings rate equal to 60 percent; in his own words “The rate of saving which the rule requires is greatly in excess of that which anyone would suggest,” adding that the utility function he used was “put forward merely as an illustration.” Not to be discouraged, he attributed this odd result to the special utility function he had chosen—implying that some other function might well give a more meaningful result, a conclusion that certainly was shared by all his readers. At this point, we may conjecture that the alternative functions that Ramsey had in mind were akin to what all his successors would come up with much later: strictly concave utility functions, for instance the immensely popular power function.

Unfortunately, it turned out that whichever functions were chosen, disaster loomed: if the savings rate fell to a more reasonable level—say 10 percent to 20 percent—at least one central variable of the economy went astray, be it the marginal productivity of capital, the growth rate of income per person, or the capital–output ratio.

Our purpose in this chapter is fourfold: (i) to indicate why such a central subject was completely forgotten for such a long time; (ii) to recall the various (failed) attempts to obtain savings rates and optimal time paths for the economy that would be meaningful; (iii) to show that not a single strictly concave utility function is capable of preventing over-investment and over-saving if the economy is initially in competitive equilibrium and to explain why this is so; and (iv) to offer a solution to the problem of optimal economic growth that systematically yields acceptable, observed time paths for all central variables of the economy, while bringing three intertemporal optima—not just one—for society.

A fundamental, long-neglected quest

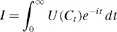

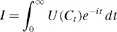

For many years, the quest for optimal trajectories of the economy remained in the realm of theory. Why was this? The reason is simple and rests upon the very nature of the problem at stake: in its most basic form, it consists in finding the optimal time path of capital K(t) or its derivative K̇(t) by maximizing the integral

subject to

| Ct = F(Kt , Lt, t) − K̇t | (1.2) |

where the dependency of the production function on t reflects the possibility that K and L are enhanced by some time-dependent technical progress factors. Even in such a simple model, if neither U(·) nor F(·) are affine functions of their arguments, the resulting Euler equation will unfailingly turn up as a non-linear second-order differential equation, which does not allow for an analytic solution. Numerical methods will be required.

In Ramsey’s days, those calculations would have had to be made by hand. Ev...