eBook - ePub

Financial Development and Economic Growth

Theory and Experiences from Developing Countries

- 380 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Financial Development and Economic Growth

Theory and Experiences from Developing Countries

About this book

This collection brings together a collection of theoretical and empirical findings on aspects of financial development and economic growth in developing countries. The book is divided into two parts: the first identifies and analyses the major theoretical issues using examples from developing countries to illustrate how these work in practice; the second part looks at the implications for financial policy in developing countries.

Information

1

MODELS OF FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENT AND GROWTH

A survey of recent literature1

Jean Claude Berthélemy and Aristomene Varoudakis

INTRODUCTION

A number of recent studies have used the endogenous growth theory to show the existence of a close association between the level of financial sector development and long-run growth. A positive association between financial development and growth has been well documented since the pioneering statistical work of Goldsmith (1969). In practice, however, governments in developing countries failed to recognise - until at least the end of the 1970s - the need to strengthen the financial system and to set up conditions favourable to financial development. During the 1950s to 1970s, the financial sector was used as an instrument to finance massively interventionist policies based on the development of key industrial sectors which were supposedly 'engines of growth'. These policies mainly took the form of directed credit allocation according to government objectives, and provision of cheap credit (by way of interest rate control and subsidisation) to the alleged key sectors of economic development. Furthermore, repression of the financial system through high reserve requirements and interest-rate controls proved to be an easy source of revenue to governments which lacked efficient instruments of taxation and were running persistent budget deficits.

The external debt crisis clearly showed the importance of relying on a well functioning financial system to be able to mobilise internal resources in order to finance economic development. Therefore, during the last 10 years, many developing countries undertook programmes of financial liberalisation, aimed at removing various policy-induced distortions that limited the development of the financial sector. However, providing sufficient internal finance for investment is not the only aim of financial sector development policies. Most developing countries are engaged in structural adjustment programmes to correct the deficiencies caused by initial import substi tution strategies. Implementation of such programmes involves removal of protectionist measures. They are slow to implement and they typically involve high costs in terms of lost output in the absence of a well-functioning financial system which could smoothly reallocate capital according to comparative advantage. Moreover, it is important that market signals be correctly transmitted, which implies among other policy measures a removal of financial system distortions, which led to parallel capital and foreign exchange markets.

All of these policy-linked reasons account for the considerable recent revival of interest in the analysis of the influence of financial development and financial sector policies on long-run economic growth. In this chapter we provide a broad survey of recent research in an endogenous growth perspective, which shows the possible contribution of financial sector development to long-run growth. In fact, financial systems perform two main functions. On the one hand, they ensure the working of an efficient system of payments. On the other hand, they mobilise savings and improve savings allocation to investment. The first section of this chapter looks at the way these functions of the financial system can contribute to growth.2 The level of economic development may, however, also influence the development and structure of the financial system. This interdependence is examined in the second section. The third section investigates the effects on growth of the 'natural' imperfections of the financial system (imperfect competition, information asymmetries) and of the distortions which arise from financial repression policies. The fourth section deals with the role of the structure of the financial system, with particular emphasis on the respective advantages of financial markets and bank-based intermediation. The fifth section concludes and points out some possible directions for further research.

FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS, THE ALLOCATION OF RESOURCES AND GROWTH

the payments system

It is probably true to say that the major contribution of a financial system to growth comes from the setting up of an efficient and adaptable system of payments. A reliable means of exchange is a necessary condition for growth. In cases where no such system exists, prohibitive transactions costs cancel out any productivity gains linked to the division of labour and the beginning of some sort of economic growth. Payments systems adapt alongside and interactively with economic growth. By definition, economic growth implies not only sustained productivity gains but also a maintained opening up of new markets and an ongoing diversification of products. The increasing complex ity of exchanges brings with it a growing monetisation of the economies, which becomes necessary in order to sustain the volume of economic activity. This in turn leads to a secular trend towards a slowdown in the money velocity as has been experienced by most developed economies (Friedman and Schwartz, 1982).

Simultaneously, the need to reduce the opportunity cost of holding money brings with it a steady movement of the system of payments towards credit relations managed by banking intermediaries. This trend is reinforced by technical advances which reduce the information costs linked to such use of credit and which make it easier to create financial assets substitutable for traditional monetary assets. This is initially reflected in the secular increase in the weight of financial activities in GDP - along with the percentage of employment in the financial sector - which is associated with economic development (Kuznets, 1971). The advances in inter mediation technology can counteract, from a certain stage onwards, the trend towards a slowdown in the velocity of narrow money aggregates. This reduction seems to be confirmed, however, for the wide money aggregates which cover more sophisticated financial assets, whose high cost of use means that they only become accessible beyond a certain level of economic development (see Ireland, 1994). This positive link up between per capita GDP and the degree of monetisation of the economy (or the ratio of the financial intermediaries' assets/GDP) was stressed in initial studies on financial development and growth. Goldsmith (1969), in his international comparative study of 36 countries over a period of a century, was even able to demonstrate that periods of strong growth coincided with accelerated financial development.

Mobilisation of savings

The existence of financial markets and/or banking intermediaries can lead to a better mobilisation of available savings by making the agglomeration of existing financial resources in the economy easier. This means that more efficient technologies can be used which require an initially high level of investment. By exploiting such non-convexities in investment opportunities, financial intermediaries can provide savers with a relatively higher yield, while also contributing directly to a rise in capital productivity and a corresponding speeding up of growth.

Moreover, this process of resource agglomeration enables financial inter mediaries to diversify the risks associated with individual investment projects and to offer savers higher expected yields (see the section beginning on p. 10). The rise in expected returns and the diversification of risks encourages financial savings rather than real assets investment with low return (such as consumer durables). Such a reorientation of savings can in tum reinforce the deepening of the financial system even further. On the other hand, substitution and income effects linked to the rise in expected investment returns have an a priori undetermined net effect on the rate of savings. Higher yields increase current consumption opportunity costs in terms of future consumption and encourage agents to transfer more resources to the future. At the same time, higher yields enable agents to realise a higher volume of future consumption for a given level of current consumption, which may in tum lead to a decrease in the rate of savings. As a result, improved mobilisation of savings resulting from the development of an intermediation system could conceptually have either a positive or a negative net effect on the economy's long-run growth rate.

In addition, the development of financial intermediation can contribute to the loosening of the liquidity constraints which economic agents frequently face when planning their life cycle intertemporal consumption. Jappelli and Pagano (1994) have looked into the incidence of liquidity constraints in a three-period overlapping-generations model, where agents borrow to finance their consumption when they are young and have no income. Later on, when they receive income, they repay their contracted debts, while at the same time saving to finance consumption during retirement. If borrowing is not readily available during the first stage, agents will find it difficult to smooth their consumption over time. This leads to an increase in the resources transferred from their most active period to retirement; in other words, to a higher rate of savings in the economy. Consequently, were liquidity constraints to be relaxed, the savings rate could fall, which could have a negative effect on the accumulation of capital and growth.

The positive relation between liquidity constraints and the savings rate has been confirmed empirically by Jappelli and Pagano on a sample consisting of OECD member countries and some non-member countries. However, any positive effect from liquidity constraints on the growth rate is based on the assumption that productivity gains are only linked to externalities in the accumulation of physical capital. But as De Gregorio (1993a) suggests, even if liquidity constraints encourage saving, they can also have a negative effect on growth. This will be the case if growth stems from the accumulation of human capital, since the borrowing possibilities for households during schooling would be reduced. It has also been demonstrated (Azariadis and Drazen, 1990; Becker et al., 1990) that the accumulation of human capital may give rise to multiple equilibria of endogenous growth if the private return on human capital investment is positively related to the collective level of educative development. The existence of liquidity constraints resulting from the under-development of the financial system could then, through the influence of externalities, make the selection of a 'low equilibrium' with weak growth more likely, which corresponds to a poverty trap situation (De Gregorio, 1993b).

Improving the allocation of resources

Mobilising sufficient resources for investment is certainly a necessary condition to any economic take-off. Nevertheless, the quality of their allocation to the various investment projects is an equally important factor of growth. The inherent difficulties involved in resource allocation- when faced with productivity risks and insufficient information on the return on investment projects and entrepreneur's skills-create strong incentives for the setting up of financial intermediation structures.

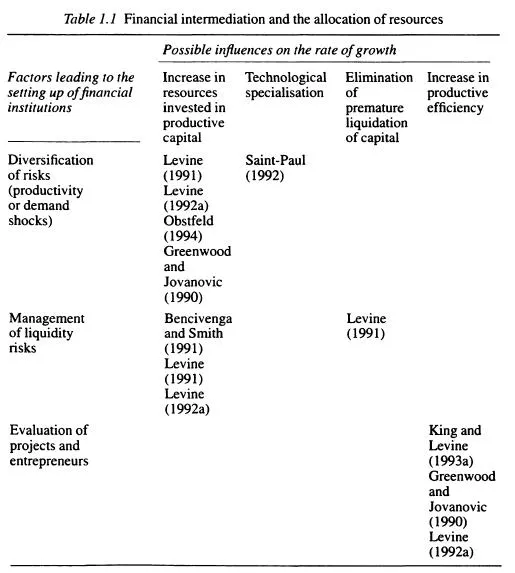

Existing theoretical work has identified various mechanisms to explain the positive incidence of financial intermediation on capital productivity and growth. It is interesting to analyse these mechanisms in relation to the inherent difficulties involved in resource allocation for investment which in tum give rise to financial intermediation activities. Table 1.1 illustrates a cross reading of existing work on the basis of these two criteria. The intermediation activities analysed can be carried out either by banks or financial markets. The

respective advantages of the two systems lie in other criteria which will be looked at later on.

The return on investment projects is subject not only to productivity risks, resulting from imperfect technological know-how, but also to risks linked to the intensity of future product demand. Productivity (or demand) risks can have two types of adverse effects on the allocation of resources:

- • first, they discourage investment by risk-averse economic agents. Poten tial investors tend to hold a considerable share of their personal wealth in the form of liquid assets which are not risky but less productive.

- • second, agents tend to make inefficient technological choices, since return on investment risks can be overcome by technological diversification, at the expense of specialisation and productivity improvement.

The first type of effect can be seen in the models proposed by Levine (1991; 1992a). The existence of productivity risks favours the emergence of stock markets or banking intermediaries which enable agents to diversify their investments. Risk diversification is direct in the case of the stock market. It is indirect in the case of banking intermediaries who, thanks to the widespread diversification of their own portfolio, are in a position to offer depositors a guaranteed return on their investments. The possibility of risk diversification encourages agents to hold (directly, or indirectly through banks) a greater share of their personal wealth in the form of productive capital. This in turn contributes directly to the acceleration of growth. Obstfeld (1994) provides an analysis of the same effect, in connection with the integration of international capital markets, assuming that more risky technologies have a higher expected yield. Promoting the integration of capital markets makes it possible for the investors in every country to diversify their high risk investments at the international level. This means that more resources will be allocated to these types of investment which stimulate global growth.

The model proposed by Saint-Paul (1992) highlights the effects of investment return risks on technological choices. Improving productivity implies selecting more specialised technology, which makes agents more vulnerable to profitability shocks arising from, for example, unforeseen variations in demand. When no financial markets exist, these shocks can be diversified through 'technological flexibility' which means choosing less specialised, and therefore less productive, technologies. The development of financial markets enables agents to reduce such risks through the diversifica tion of their investments, while at the same time choosing more productive and specialised technology. From this point of view, developing financial markets seems even more attractive, especially as the opportunity cost (in terms of productivity loss) involved in flexible technology is high. Saint-Paul (1993) uses the same approach to look at the problem of dual technology often found in developing countries, in relation to the level of development of the financial sector. Technological dualism can also be interpreted as a form of technological risk diversification, when it is impossible to diversify pro ductive risks in the modern sector effectively because financial markets are underdeveloped.

A second factor which plays a role in the setting up of financial institutions is the presence of liquidity risks. These are due to the fact that some productive investments are highly illiquid, in the sense that any premature sale of these assets implies a heavy cutback in their yield. In the three-period overlapping-generation models studied by Bencivenga and Smith (1991) and by Levine (1991; l...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Financial Development and Economic Growth

- Routledge Studies in Development Economics

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- List of contributors

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 Models of Financial Development and Growth: A Survey of Recent Literature

- Part 1 Theoretical and empirical issues in financial development and economic growth

- Part 2 Issues on financial policies in developing countries

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Financial Development and Economic Growth by Niels Hermes, Robert Lensink, Niels Hermes,Robert Lensink in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.