![]()

1 Global Economic Crisis and the Developing World

An Introduction

Ashwini Deshpande and Keith Nurse

This introduction is being written at a time when the “Occupy Wall Street” movement is in its third week and continues to gather momentum in the United States of America. On the other side of the Atlantic, European leaders have delayed by two weeks the summit to finalize the bailout plan for Greece and the wider eurozone debt crisis. And to add more drama to the sequence of events, the cover story of this week’s issue of The Economist is entitled “Be Afraid”, with the tagline stating “unless politicians act more boldly, the world economy will keep heading towards a black hole” (The Economist, 2011). Also of note is the passing of the US Senate bill aimed at punishing China and other countries that the US deems are undervaluing their currencies. The Chinese response through its official news agency Xinhua stated that the “US legislation was reminiscent of the Smoot-Hawley tariff act in 1930 that is widely credited with worsening the Great Depression” (Financial Times 2011a).

In an unrelated but topical bit of trade news it is reported that Chinese exports, now considered a barometer for the health of the global economy, fell in September by seventeen percentage points – the biggest drop since 2009 – due in large part to the decline in orders from the EU and the US, China’s biggest export markets (Financial Times 2011b). Coupled with this is the latest employment news that the global economy has lost twenty million jobs since the outbreak of the financial and economic crisis in 2008, and that a further twenty million jobs could disappear by the end of 2012 based on current trajectories (ILO/OECD 2011). The specter of rising unemployment, declining consumer demand (and confidence), reduced investor confidence and constricting government spending are the key challenges facing the recovery effort after the furor of bank bailouts, stimulus packages and debt restructuring that defined the policy response in the immediate aftermath of the financial and economic crisis.

There is now a foreboding sense that the volatile mix of fiscal austerity, rising social discontent and political gamesmanship may lead to the further growth of low-intensity protectionism, or worse yet, the return of beggar-thy-neighbor policies (e.g. currency wars), thereby further threatening the already fragile global economic recovery. As the prospects of a double-dip recession become more evident and the predictions of sustained recovery fade there is increasing recognition that the global economy is in the throes of a global economic crisis reminiscent of the great depressions of the 1930s and possibly that of the 1870s and 1820s. As such, the current crisis should be seen not just as a period of financial and economic instability but as a more fundamental shift in the geo-economic and political moorings of the contemporary global economy (see Nurse 2010). For example, Gourevitch, in his seminal work on comparative responses of five governments (United States, United Kingdom, France, Germany and Sweden) in the advanced economies during international economic crises, noted that each of the previous crises exhibited similar tendencies, such as there was in each case a major downturn in a regular investment/business cycle; a major change in the geographical distribution of production, and, lastly a significant growth of new products and new productive processes (Gourevitch 1986).

What is observable in the contemporary conjunctural shift has been the significant shift in economic power away from the advanced economies towards the emerging and developing world. For instance, the share of global GDP of the G7 countries dropped from 50 percent in 1990 to 40 percent by 2008 while the share of the G20 emerging economies rose from 11 percent to 17 percent in the same time period (Canuto and Yufa Lin 2011). It is also critical to note that the main source of growth in the global economy has come from emerging economies followed by developing countries, generally.

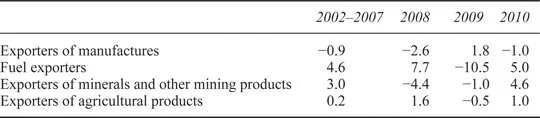

The growth performance and the prospects for recovery are uneven and largely dependent on the trade structures of the respective developing countries (see Table 1.1). The economies most severely affected are the net food and energy importers, on account of the rise in food and energy prices in global markets. The countries worse affected are the small and island economies due to the high dependence on imports in these areas. Exporters of manufactured goods also suffered during the downturn depending on the extent of their exposure to the advanced economies that are in a recession. Exporters of fuel and exporters of minerals and other mining products experienced the most favorable terms of trade, followed by the exporters of agricultural products.

Table 1.1 | Income gains or losses from the terms of trade of selected developing and transition economies, by trade structure, 2002–2010 percentage of GDP |

Trade in international services, a sector where many developing countries are highly dependent, was also impacted by the economic downturn, as reflected in data for 2009. Travel and transport, which together account for half of the world trade in services, had respective declines of 9 and 16 percent. The next most negatively affected sectors were personal, cultural and recreational services (11 percent), financial services (16 percent) and construction services (20 percent). The only areas that experienced growth were trade in computer and information services (3 percent) and royalties and licence fees (19 percent) (United Nations 2011a).

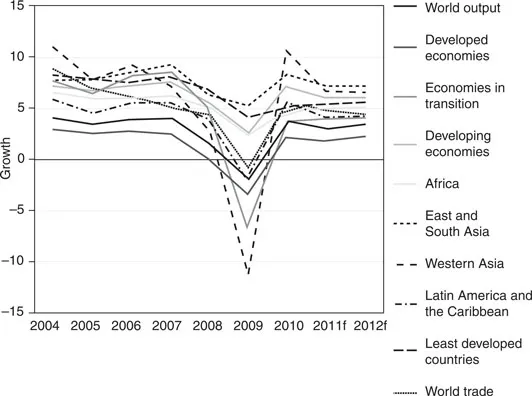

In total, world trade took a major and unprecedented hit, with a decline of minus 11 percent in 2009. The last time world trade fell by this much was during the Great Depression of the 1930s (see Figure 1.1). However, data and analysis of the global trade imbalances (GTIs) suggest that the trade problem is structural rather than episodic, showing that the average annual growth of GTIs for the period 1990 to 2007 was 11 percent as compared to 1 percent in the prior two decades (Freund 2011). From this standpoint, rebalancing current account imbalances is a critical feature of the post-crisis policy framework if sustainable growth is to be achieved (Serven and Nguyen 2011). Achieving coordination in this arena is no mean task, given the divergence of perspectives from the key actors. For example, the US points to the under-valued Chinese currency, whereas China and the other emerging economies argue that the greater distortion is the excessive quantitative easing, particularly in the US (United Nations 2011b).

Figure 1.1 | Growth of World Output, by Region, 2004–2012 (Source: UN 2010, 2011). |

From a regional perspective, an analysis of the growth performance in the last few years provides a very compelling picture of the unfolding context of growth and recovery. As Figure 1.1 illustrates, overall world output experienced a major drop-off of minus 2.0 percent in 2009, with a recovery of 3.6 percent in 2010. The advanced economies had a below-average performance, with a decline of minus 3.5 percent and a slight recovery of growth in 2010 of 2.3 percent. Developing countries, on the other hand, only had a decline to 2.4 percent, rebounding to 7.1 percent in 2010 and thereby returning to pre-crisis peaks. The success of this group is largely determined by the strong export performance of East and South Asia, namely China and India, which have been averaging output growths of 10 percent and 8 percent, respectively, over the 2004–2010 period. Africa’s average was closer to 5 percent, whereas Western Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean hover around 4 percent.

What Figure 1.1 depicts is what has been described as the “two-speed global recovery” process and the sustained imbalance between surplus and deficit countries. Several emerging economies, namely China, Brazil and India, have built healthy foreign exchange reserves on the basis of solid export performance that generated strong current account positions. As for the larger emerging economies, they have been able to rely on large and relatively under-tapped domestic markets or to switch to South–South trade to ride out the slump in external demand from the OECD countries in recent years.

On the other side of the equation are the advanced economies that have been mired in low growth with rising unemployment, faltering consumer spending and high debt levels along with widening trade and reserves deficits. The US, whose prospects are slightly better than that for Europe and Japan, “has been on the mend from its longest and deepest recession since the Second World War” and the “pace of the recovery has been the weakest in the country’s post-recession experience” (United Nations 2011c). The Eurozone area is affected by sovereign debt problems, harsh austerity measures and structural and/or technological unemployment, particularly in Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, Spain and the UK. The prospects for growth rebounding in these economies are very weak in the short to medium term.

Most developing countries, other than the fast-growing emerging economies mentioned above, have been affected by the slowdown in traditional export markets and external financial flows such as FDI, aid and remittances, and have had to implement austerity measures. Some developing countries have been buoyed by increased commodity demand, from China in particular. However, in general it is noted that poverty, hunger and inequality are on the rise in the developing world, in part as a result of the depth of the austerity measures that most governments have been required to implement. It is also important to note that developing countries continue to hemorrhage massive amounts of financial resources to the advanced economies. One of the presumed benefits of the current crisis is the decline of net transfers of financial resources in 2009 (–$545 billion) and 2010 (–$557 billion) from the peak of –$881 billion in 2007. On the other hand, net private capital flows rebounded from the slump in 2008 ($110 billion) to $386 billion in 2009 and $659 billion in 2010 (United Nations 2011d). Similarly, remittances, which also took a dip in 2009 to US$309 billion, rebounded to pre-crisis levels in 2010 ($325 billion) and are expected to rise in 2011 to $349 billion (Mohapatra et al. 2011).

These shifts have created a new global social redistribution of income quite unlike the post-World War II model, where the North Atlantic economies were the principal drivers of economic growth that provided the demand push behind late twentieth-century economic development. While the growth of the emerging economies like the BRICS has been rapid, the largest share of global GDP still comes from the G7 economies and the former countries are still very reliant on these markets.

This scenario raises the question of where the new source of world demand and consumption will come from to propel the global economy out of the downturn. Most economies in Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, the Middle East and Asia, given their levels of external indebtedness, high unemployment and general impoverishment, are not to be that source. On the positive side, one of the potential new engines of growth is the global middle class in emerging economies, and this target group has become far easier to tap into with the growth of global media and the Internet economy. However, is this demand sufficient to compensate for the fall-off in demand from the advanced economies? In effect, the unfolding context is one where workers in the G20 are producing goods and services for markets that are severely constrained in the current global economic crisis. More fundamentally, the situation relates to the tendency for world production to outstrip world consumption during the latter phases of an economic downturn (see Mandel 1984, Wallerstein 1984).

The combination of these structural shifts in the global economy establishes the basis for major instability as the existing international economic regime is challenged by the weight of unrealistic expectations within and across countries. As such, the difficulties of generating consensus among the major economies and the inadequacy of a unified global policy response make for a dangerous economic and political context. Ben Bernanke, chairman of the US Federal Reserve, at the Sixth European Central Bank Central Banking Conference in Frankfurt, Germany in November 2010, argued along similar lines. The following quotation from him is worth highlighting because it captures both the historical dimension of the current crisis as well as the risks of uncoordinated rebalancing of the contemporary global economy:

As currently constituted, the international monetary system has a structural flaw: It lacks a mechanism, market based or otherwise, to induce needed adjustments by surplus countries, which can result in persistent imbalances. This problem is not new. For example, in the somewhat different context of the gold standard in the period prior to the Great Depression, the United States and France ran large current account surpluses, accompanied by large inflows of gold. However, in defiance of the so-called rules of the game of the international gold standard, neither country allowed the higher gold reserves to feed through to their domestic money supplies and price levels, with the result that the real exchange rate in each country remained persistently undervalued. These policies created deflationary pressures in deficit countries that were losing gold, which helped bring on the Great Depression. The gold standard was meant to ensure economic and financial stability, but failures of international coordination undermined these very goals. Although the parallels are certainly far from perfect, and I am certainly not predicting a new Depression, some of the lessons from that grim period are applicable today. In particular, for large, systemically important countries with persistent current account surpluses, the pursuit of export-led growth cannot ultimately succeed if the implications of that strategy for global growth and stability are not taken into account.

(Bernanke 2010)

Regardless of the contending perspectives, it is undeniable that the burgeoning protest movements, on both sides of the North Atlantic and in the South, capture public outrage at the fact that a large share of the working classes (the industrial workers, the middle classes and so forth) are paying a debilitating and unequal price for the crisis, as unemployment and inequality continue to remain high and expand. The advanced economies continue to have slow growth, and the policy initiatives are principally focused on imposing stronger austerity measures, rather than stimulating productive economic activity which has the potential to create jobs, boost living standards and significantly mitigate economic hardship. These same economies, however, are constrained by ballooning fiscal deficits and worrisome debt-to-GDP ratios on account of the fall in tax revenue and the burden of bank bailouts and stimulus packages.

The competition between short-term fiscal austerity measures and longer-term growth and expansion policies reminds us that in hard economic times policy debate and political experimentation is at its sharpest and most controversial (Gourevitch 1986). It is also noteworthy that the global economic crisis has erupted at a time when the global economy is integrated, intertwined and interdependent as perhaps never before in history. Thus, the impact of this crisis that originated in the advanced industrial countries can be felt sharply in the developing world, which is already grappling with its own internal constraints and structural barriers to sustained development. It is on this basis that Krugman (2008) argues “the spread of the financial crisis to emerging markets makes a global rescue for developing countries part of the solution to the crisis.”

Emergent debates about resurgent protectionism, currency wars and alternative reserve currencies suggests that the global economy has entered a phase of heightened geo-economic and political change which will transform the development “equation” in varied and diverse ways. Indeed, the economic and financial crisis is but one element of the global transition, given what is referred to as the “triple crisis” of finance, development and environment with challenges like climate change that underscore the limits of the global economy. It is imperative at this time that development economists and policy-makers should engage with two crucial questions: the implications of these changes for the developing world and the prospects for “development” for the majority of people in the developing world. This volume hopes to contribute to this engagement.

The Scope of the Book

This is the third volume to emerge from the rigorous academic research and lively discussions among young scholars associated with the Annual Conference on Development and Change (ACDC). The ACDC is an international network of heterodox young scholars, mainly development economists, but not exclusively, as it includes sociologists and non-academic practitioners as well. The network has had four conferences, and this volume contains selected chapters from the fourth conference, which was held in Johannesburg in April 2010. Space constraints prevented us from including all the papers presented; we hope this selection showcases the wide variety of angles and approaches with which participants approached the discussion on the global economic crisis and its impact on the developing world. The book is divided into six parts, with one of the parts turning the spotlight on South Africa, given that the conference was held there.

Part I: Insights from History

The first part takes a historical view of some components of globalization and their impact on the developing world. There is also an...