1 Introduction and summary of the book

After almost 15 years of deflation and recession, in Japan the issue of what is an attainable rate of growth consistent with price stability and equilibrium in the government budget has become a matter of political concern. Can Japan, like the United States, achieve a higher rate of output growth, or must the Japanese economy plan on continuing on a slow growth path? That is the focus of this research.

A Japanese version of a “Rising Tide Policy”

Several years ago, a Japanese high school student wrote a composition entitled “Japan Has Everything, except a Dream.” We recalled that title when we recently read the official report of “Japan’s Vision for the 21st Century,” published by the Japanese Cabinet Office in April 2005 (Council on Economic and Fiscal Policy, 2005). It described a “Targeted Future State” that paints a picture of an economy where two things are essential:

- The ability to maintain a 1.5% annual economic growth rate until the year 2030.

- A growth rate of per capita real GDP of about 2%, a little higher than the growth of aggregate GDP reflecting a declining population.

Accelerating the growth rate of an advanced industrial country like Japan is a considerable challenge. Many of Japan’s industries are mature and are already operating at the technological frontier. It is hard for a country to prosper if, as in Japan, its population shrinks and ages. Solving Japan’s economic and social problems such as an excessive fiscal imbalance and growing public debt, an aging society, and growing pension demands cannot be accomplished without expanding the economic pie. Moreover, Japan is still adapting its industrial structure to the radical changes in its competitive position relative to other East Asian countries.

A pessimistic appraisal of Japan’s prospects may turn out to be a self-fulfilling prophecy. Who will invest in a country whose likely annual growth rate is a mere 1.5–2%? Human and financial capital will flow out of a country with little or no hope for future expansion and profitability. Other Asian countries will not allow Japan to take a leadership role in the region if Japan is expected to grow at a glacially slow annual rate through the foreseeable future.

This pessimistic scenario implied by the government’s economic projections should be considered a very serious warning, a wakeup call to the nation. Without a more aggressive forward-looking strategy, the people of Japan will suffer the effects of slow economic growth for many years in the twenty-first century. The increasing burdens of an aging population will be an unfortunate legacy for younger generations.

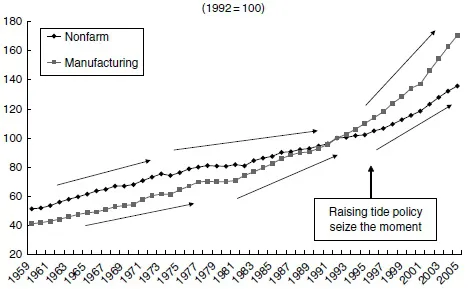

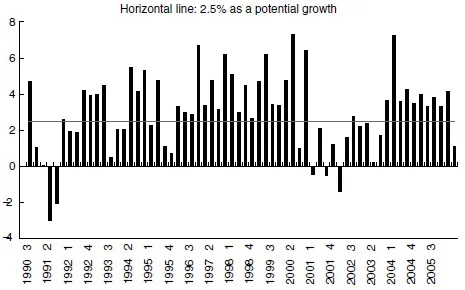

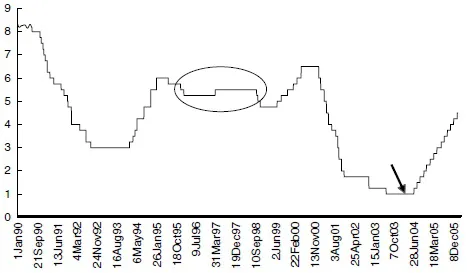

In the early 1990s, the Japanese were not the only ones taking a pessimistic view of higher economic growth. At that time, many people in the United States feared that the US economy had also reached maturity, and that there would no longer be great technological innovation to drive the economy. The consensus among economists about the US potential GDP growth rate was only about 2–2.5% per year, with productivity increasing only 1–1.5% annually. But, in the mid-1990s, some American economists began to recognize that the United States could grow at a faster rate than had originally been anticipated without accelerating inflation. One of those economists was Prof. Lawrence R. Klein, who noticed that the economic recovery that occurred after 1991 was characteristically different from past economic recoveries, as described in his 1995 paper, “The Re-Opening of The US Productivity-Led Growth Era” (Klein and Kumasaka, 1995). In that same year, Jerry J. Jasinowski, President of the National Association of Manufacturers, joined a small group of business economists who believed that the US economy could grow at a faster rate. Jasinowski collected about twenty professional papers that discussed economic policies detailing how this could be achieved. The papers focused on the New Economy, productivity, human capital, globalization, the role of government and fiscal and monetary policies. These papers were published as a book The Rising Tide in 1998 (Jasinowsky, 1998). The title was gleaned from a quote of President J. F. Kennedy during the 1962 GATT/Kennedy round of trade talks. He remarked that “a rising tide lifts all boats,” that is, that all countries would be better off through growth generated by international trade. This notion also applies within a country, domestically. Rapid growth is likely to spread benefits broadly throughout the society. If growth is slow, some groups are always left behind and their incomes do not improve. A “Rising Tide Policy” that lifts all boats is essential for the general welfare of all. It was fortunate for the United States that American economists recognized that their economy had the potential for faster growth in the mid-1990s. As Figure 1.1 shows, the productivity growth trend for the United States rose steadily since 1995. As seen in Figure 1.2, since that time economic growth averaged 2.5% (Figure 1.2), a rate that was, by general consensus among many economists, believed to be the potential growth rate for the period from 1995 to 2000. Luckier still, Alan Greenspan, Federal Reserve Chairman at the time, also recognized the increased productivity growth trend and resisted pressures to increase the interest rate in the early stages of economic expansion. The short term interest rate, which had been between 5% and 6% in the mid-1990s, was reduced from 2001 to the extraordinary low level of 1% in 2003, and was increased only very slowly in the 2004–2006 period, providing continued stimulus to the economy over several years. Such an accommodative monetary policy stance, based on the assumption that productivity gains would offset increases in labor costs as the employment situation tightened, contributed to the long economic expansion seen in the 1990s and early 2000s (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.1 US productivity growth trend: nonfarm and manufacturing sectors.

Figure 1.2 US real GDP growth rate (% per year).

Now, it is time for Japan to introduce her own “Rising Tide Policy.” It has been unfortunate that many Japanese economists and business people misunderstood the potential of information technology in the 1990s, when the Information and Communication Technology (IT) revolution began. In view of the structural rigidity of the Japanese business scene and the fact that many business people viewed the IT revolution largely as a speculative bubble, they did not sufficiently adopt the new technologies in the 1990s. Japan did not see the increase in productivity growth through the IT revolution that was observed in the United States. It was not until after the bubble in the US stock market burst in 2000, that many Japanese businessmen recognized that IT was not a modern day tulip mania. Adam Cohen, writing in the New York Times expressed it best “. . . when the tulip bubble burst, nothing is left but soapy residue. But, the Internet revolution is really changing the world” (Cohen, 2002). Japan lost at least five years before trying to utilize IT effectively. As a result the Japanese economy found itself on a slow growth path, one that threatens long-term prospects.

Figure 1.3 US federal funds rate (target rate after July 13, 1990) (%). (Dates on horizontal axis correspond to times when interest rate targets were changed.)

In this project, we focus mainly on a theoretical and policy framework that will raise Japan’s potential growth. In an earlier stage, Stage I (January–March 2006), we surveyed the effect of IT on economies in the United States and East Asian countries, and proposed a new theoretical structure for analyzing the relationship between IT and productivity growth. In the second stage, we applied this theory in a modified econometric model and carried out alternative forecast simulations. We use this work to propose fiscal and industrial development policies, particularly with regard to IT and its application, to raise Japan’s potential growth. The structure of this book is as follows:

- Historical view of the performance of the Japanese economy over the long term and in the recent past.

- The nature of IT and its implications for a New Economy.

- A new theoretical framework to analyze the relationship between IT and the growth of potential GDP.

- The implications for fiscal and monetary policy of a faster growth path for potential output.

- Japanese development in the context of the East Asian growth process.

- IT and productivity growth in Japan.

- Industrial organization in Japan and the United States.

- A case study of the telecommunications industry in Japan.

- IT and productivity growth in the United States.

- A macroeconomic model for Japan, that embodies the “New Economy” production function.

- Simulation studies of Japan’s higher economic growth.

- Policy recommendations to accelerate Japan’s economic growth.

The Japanese economic growth policy controversy

The issue of establishing an appropriate growth target has become particularly important in recent years as Japanese economic performance has lagged. Japanese government officials have long found it difficult to reconcile the various aims of economic policy—rapid growth, price stability, international payments balance, and fiscal equilibrium—when different, often independently operating, government agencies have focused their responsibilities separately on one or another of these objectives.

For example, the Ministry of Finance has had great concern with regard to the fiscal deficit and the national debt, seeking when possible to reinstate taxes to minimize the current fiscal deficit. A good example of that was the premature reinstatement of the consumption tax in 1997 that drove the gradually improving Japanese economy back into stagnation. Today again, the Ministry of Finance is seeking substantial consumption tax increases, not only to improve budget balance on a current basis, but also in fear of a rising ratio between the public debt and national income, now at the high level of approximately 170%.

Similarly, the Bank of Japan is seeking to manage its monetary policy with focus on a narrow definition of inflationary objectives. For many years, in the face of deflation, the Bank of Japan followed a zero interest rate policy. Indeed, while nominal interest rates were at 0 or 1%, about as low as they could be, real rates of interest were somewhat higher, some 2 or 3%, because the price level was declining. Now that deflation has stopped and prices are rising at a modest rate, the Bank of Japan wants quickly to raise interest rates to ward off the risk of inflation. Unfortunately, rising interest rates at this time might not only slow gradually resurging Japanese economic growth. They might also impose added strain on fiscal balance as interest payments on the large outstanding debt would increase. Higher interest rates might also appreciate the Japanese yen again, as in the 1990s, reducing the competitiveness of Japanese goods in world markets.

Economic targets are necessary so that policymakers can make the critical policy decisions that guide the economy consistently toward its various objectives. They are particularly important in an economy like Japan’s that remains on the edge between prosperity and recession and that greatly fears inflation.

Even during the long stagnant period 1995–2005, arguments were levied against a policy of fiscal expansion because of the public debt overhang, and a fear of inciting inflation, even though deflation was one of the problems that the economy faced. Fiscal stimuli were often brushed aside on two grounds:

- The public deficit was too large, even though there was criticism that it was not properly measured1;

- It was claimed that public works were already plentiful.

In 2006, the specifics of the economic situation have placed the policy controversy on the front burner. A political battle raged between two groups within the Japanese Council on Economic and Fiscal Policy concerning the prospect of Japan’s post-Koizumi Administration economic growth over the next decade. The debate focused initially on how to reduce the government deficit.

The first group was led by Hidenao Nakagawa, Chairman, Policy Research Council in the Liberal Democratic Party and Heizo Takenaka, Minister of Internal Affairs and Communication. This faction, which we will call the “high growth” group, projected the future on the basis of a 3–4% growth rate for nominal GDP. Such a growth path translates into 3% annual growth of potential output in real terms, a substantial improvement over Japan’s inadequate growth record of the past 15 years. Moreover, as we show later, such a growth path would yield increases in tax revenues sufficient to stabilize the government deficit without requiring immediate increases in the consumption tax.

The second group, which we will call the “low growth” group, was directed by Sadakazu Tanigaki, Minister of Finance, and Hajime Yosano, Minister of State for Economic and Fiscal Policy as well as Minister of State for Financial Services. This group insisted that Japan’s potential growth was only 1.5%, a straightforward assumption because the average growth rate of real GDP in Japan was approximately 1.5% over the past decade. They did not expect higher economic growth and so they argued that an immediate increase in the consumption tax would be necessary to reduce government deficits.

The short term political impact of this debate was considerable since it was aimed at the very basics of tax policy decisions: whether, once again, to raise the consumption tax. Moreover, when economic policies are planned for the next decade, a difference of 1 or 2% in annual economic growth can give a very different picture of the future. Note, also, that adopting a low growth projection can be a self-fulfilling prophecy. In a complete dynamic economic system, an increase in taxes may have a depressing effect on GDP and on its growth path. Such a tax increase would be accepted by policymakers if its macroeconomic consequences are consistent with their underlying “low growth” plan. When the two groups failed to resolve their dispute, Prime Minister Koizumi asked Nakagawa to prove that Japan would be able to achieve a 3% sustainable growth rate. That request was the basis for the present study.

Policy potentials for faster growth

Policies leading to a more rapid increase in growth rate involve a number of possibilities:

- More aggressive macroeconomic policies. Since it is anticipated that productivity growth will be faster, it would be possible to push macroeconomic activity more vigorously, with stronger fiscal policy and more accommodative monetary policy, without causing inflation.

- Market improvement policies. Removing the regulatory constraints that affect many service industries in Japan and improving the competitive functioning of markets may go a long way toward achieving improved productivity.

- Sector-specific industrial policies favoring IT industries. High-tech industries fit well with Japan’s resource and skill endowments: skilled labor, abundant capital, and advanced high-tech engineering technology. There are also other fields, like distribution and financial services, where significant gains in productivity can be made. Policies that will promote Japan’s development and application of IT technology and policies that will provide education, research and entrepreneurship will help to make a substantial contribution to more rapid growth.

The policy options for Japan will be considered at greater length in Chapters 2 and 13.