![]()

Part I

Theory, policies and institutions to exit from the crisis

A macroeconomic approach

![]()

1 Bridges to Babylon

Critical economic policy – from Keynesian macroeconomics to evolutionary macroeconomic simulation models

Hardy Hanappi

Comments and explanations of the worldwide social crisis, reaching from economic and political turmoil to a multi-faceted cultural decline, are flooding the information environment. It is not just the sheer quantity that has arrived at an all-time high; it is also the vehemence of the style of contributions, which is impressive. It shows that scientists and the popularizing media across many disciplines are learning that the last five years are turning out to be the prelude to a major reshaping of human society. But unfortunately enough, the core sciences needed to structure the discourse, namely the three social sciences (political science, economics, sociology), proved unable to provide even the basics of a common language able to debate the newly emerging phenomena. The division of labor in scientific work, which dominated the after-war development, has left a completely disjoint field of specialists expressing themselves in a multitude of professional jargons. Moreover, the institutionalized rules for successful academic careers further amplified the tendencies to ever more singular formal and informal styles, producing academic islands and insider schools. Travels between these islands became cumbersome and ruined chances to get tenure at a respectable academic institution. As soon as a unifying event, e.g., the current global crisis, occurs and scientists are asked for explanations it suddenly becomes visible: The tower of Babel erected by scientists is inhabited by tribes whose languages have been confounded – not by an anxious God afraid of losing its omnipotence (as in the ancient legend), but as a joint product of the misunderstood primacy of the methodological principle of steadily increasing specialization and a loss of public support for synthetic theory building. We are confronted with a scientific Babylon, an arcane church built of highly sophisticated pieces of knowledge, which nevertheless remains mute – amidst the white noise of singular comments – with regard to a sensible understanding of contemporary global political economy.

This chapter will only to a limited extent point at the shortcomings of mainstream economics; there already exists an enormous amount of valuable critique, in theoretical investigations as well as with respect to empirical research. In the current political situation what is needed even more is to collect and to synthesize the existing valid pieces of the knowledge puzzle “political economy.” In other words, to build and to rebuild bridges: bridges built of a language enabling mutual understanding between the tribes living on the island of science – Babylon; but also bridges that enable intellectual travel from the ivory tower of knowledge development to the mundane mainland of ordinary inhabitants of the planet – and back. This idea was the motive for stealing the strange title of the chapter from an album of a famous rock and roll band.

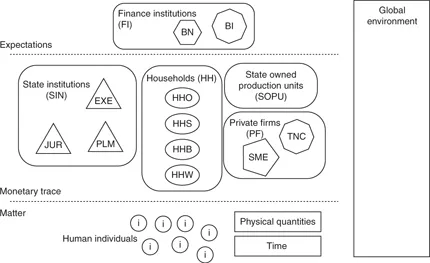

As a preparatory device, bridge-building needs the fundament of a set of entities, or pillars, which can be connected to the diverse theoretical continents. What are the elements to which political economy refers to? Figure 1.1 provides the proposal on which all of what follows will be based.

Figure 1.1 The entities of political economy.

At the lowest level the human species consists of individual members of the species (i), which interact physically in a material environment. To enable their reproduction as species, i.e., beyond the short lives of the individuals, human societies are a cooperating unit with the capability of internal communication. For thousands of years this unit has used a language element, a sign, for the social value of a procedure or the product of a procedure. The material carrier of this sign of social value is called “money” (cf. Hanappi 2013a). The level above the individuals shows the social institutions which are necessary to regulate the primary metabolism of the species: state institutions (eventually divided into Montesquieu’s three functions:1 PLM, LEG and EXE), production units (eventually divided into state-governed and private firms, the latter again distinguished as2 TNCs and SMEs) and households (eventually divided along the dominant form of income3: HHO, HHS, HHB and HHW). To the right of this national setting the fact that nations collide – increasingly are forced to find forms of survival between dominance and cooperation – is summarized by a box labeled “Global environment.” In macroeconomics of open economies this box typically would be filled with just another copy of all the entities on the left to depict the two-country case. Note that for each of the two countries a different content of production units, households and state elements can be specified. More on this topic follows in Section 4. Finally, on top of the figure the entities driving the meta-rules of finance are shown (eventually divided into local national players and large, globally acting entities); again Section 4 will elaborate on this issue. The level of granularity of Figure 1.1 has been chosen in a way that should show some major network structures typically used in theory building on this set of entities, while avoiding too much detail.

Equipped with this set of entities, the bridge-building exercise4 can be started.

1 Macroeconomics (from Walras to Keynes and back)

The last grand attempt for a unified economic approach, linking Keynes’ ideas on macroeconomic aggregates with the standard microeconomic optimization framework, was the so-called “neo-classical synthesis” developed5 from 1947 till the 1970s. Starting with the Walrasian component, a sensible point of departure is to highlight how the marginalist revolution of 1874 (led by Leon Walras, Stanley Jevons and Carl Menger) had been a response to classical political economy, in particular a refusal to its final zenith in the work of Karl Marx. Put in a nutshell, the latter had claimed that aggregation along the lines of class distinctions provides a theory of exploitation. In short, the driving force of capitalism is the total of firm owners’ activities to maximize profits, and total profits are the difference between total revenues and total cost. The limits to increase revenues – the product of quantity sold times the (average) price of a unit – are given by production technology, market conditions (competition) and constraints on the demand side (taste and income, and wealth of potential consumers). On the other hand, total cost can be minimized if the major component of cost, i.e., wage cost, is as small as possible. This can be guaranteed by permanent unemployment with which a competitive labor market6 forces the wages of employees down to a subsistence level, while simultaneously firm owners try to introduce new technologies which allow them to reduce the number of workers needed for a given amount of output. Fewer workers at lower wages results in a lower wage sum, which then subtracted from higher revenues will provide higher profits. The price–wage system sketched in this synopsis is the core of the exploitation theory of classical political economy, not just in Marx’s work but across the whole generation of authors.7

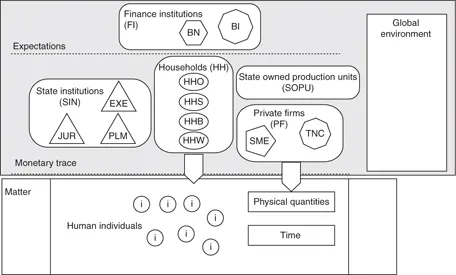

The authors of the marginalist revolution proposed a completely different theory of prices. This was possible by first narrowing the scope of theory: Consider just the aggregate of all households (HH), and its demand for a given finite set of physical products owned by different firm owners (PF) and focus only on the physical correlates of these two stereotypes.

While the larger picture of Figure 1.1 is dramatically reduced compared to Figure 1.2, there is at the same time a false generalization that takes place. Each household is set equal to a single human individual (i) which can choose to allocate its income to buy from the set of predetermined physical goods also owned by physical individuals (i). This theory of prices thus starts with the assumption that there exists an atomistic material structure of smallest entities (individuals) which possess quantities of goods. To get dynamics into this picture, which then can be interpreted as the emergence of a price structure, an additional innate property has to be ascribed to each atom:8 a preference order concerning the different goods. If what they possess differs from what atoms would prefer to possess, then algorithms for exchange processes can be specified – see Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.2 Marginalist reduction.

For certain specifications of preference orders, which look plausible as long as no new commodities are introduced, it was possible to show that there exist exchange relations, which can eliminate all possibilities of improving the utility of any one atom without reducing the utility of a...