1 Setting the scene

1.1 Introduction

Most government expenditure is geographically specific. This is manifest in the vast number of local institutions that arrange the financing, regulation and provision of public services, such as local governments, courts, schools and hospitals, and the natural preference of service users to secure access to public services locally. The major exceptions to this localism are a small number of national public goods, such as defence and international relations, and some (but not all) systems of welfare payments. Yet even these programmes can have important local dimensions, for example in the form of the choice of location for a military airport.

It can be argued that – because local people enjoy the benefit of local public services – they should be funded solely through local taxes and charges. Indeed this was the dominant principle underlying early systems of local government in the UK, most notably the provisions of the Poor Law of 1602, which for over 200 years placed the financial responsibility for poor relief on local parishes. However, this principle became unsustainable. A central concern was the coincidence of high spending needs and low taxable resources that occurred in the poorest jurisdictions. This gave rise to pressures for needy citizens to emigrate to more generous parishes, and an incentive for parishes to stint on poor relief, in order to discourage such emigration (Keith-Lucas, 1980).

As a result, a series of reforms in the nineteenth century created the precursors of modern local government, in Britain, Europe and elsewhere. A central feature of the reformed systems was a desire to effect financial transfers from richer, low needs areas to poorer, high needs areas in order that certain minimal standards could be secured everywhere. In England, such transfers were effected through a range of central government grants-in-aid to local governments. Bennett (1982) cites examples from the nineteenth century in fields as diverse as prisons, police, roads, schools, sanitation and housing.

Thus, even when public expenditure is undertaken locally, national or regional government has a crucial role in financing and influencing the nature of local public services, through its financial equalization role. An extensive literature has now developed in the field of fiscal federalism, which seeks to model the economics of grants-in-aid from central to local government (Oates, 1999). Many of the principles of fiscal federalism often apply even when the local organizational unit is not a tier of government, but rather some other administrative unit (such as a welfare benefit office) or a local service provider (such as a university). The role of public finance in local public services is discussed in more detail in Chapter 2.

The remainder of this chapter sets the scene for the book. I first seek to clarify terminology and then outline the various forms of funding mechanism found in most systems of local public services. The chapter then introduces the notion of formula funding, and discusses the broad arguments for its use. The chapter ends with a brief description of some landmarks in formula funding of UK public services, and an outline of the remainder of the book.

1.2 The flow of funds in public services

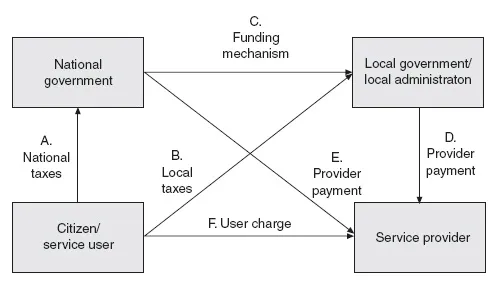

In order to secure clarity about the terminology used in the book, Figure 1.1 offers a conceptual framework for the flow of funds implicit in the finance of local public services. The prime source of central government funds is taxation, paid in a variety of forms by citizens and businesses. This creates a pool of revenue (A) available to the government, which must decide how it will allocate the funds to support locally delivered public service programmes, either wholly or in part.

The central government might pay local providers directly (E), as for example in the US Medicare programme of health care for older people. However, national governments usually devolve purchasing powers to lower tiers of government, such as states, regions or various forms of local government or local administration. Throughout, I usually refer to these devolved administrations as local government. They are to a greater or lesser extent financed by grants-in-aid from the central government funding mechanism (C).

Figure 1.1 The flow of funds in public services.

Local governments may be solely reliant on national funds, but are often able to augment their revenue with local taxes (B). They then purchase services from providers (D). In some circumstances, the distinction between purchaser and provider may be unclear (for example, schools are often directly provided by local governments). However, even where there is no explicit payment mechanism, local governments must in principle purchase their services from vertically integrated providers. Finally, the service user might be required to pay a charge to the local government or directly to the service provider (F).

In practice, the flow of funds may be more complex than this schema suggests. For example, regional local governments might in turn devolve some purchasing powers to municipalities, or police authorities might devolve funding to local operational units. There are also other potential sources of funds, such as commercial municipal businesses. However, in essence, the six flows shown in Figure 1.1 represent the most important conduits of finance found in most public sectors. Indeed, the funding of many public services can be much simpler than this general schema, for example, when there are no local taxes or user charges.

This book is centrally concerned with just two of the funding flows represented in Figure 1.1: the mechanism for funding local governments from national revenues (C); and the mechanism that local governments use for paying providers (D). In addition, by addressing flow D, the book will implicitly address situations in which national governments pay local providers directly (E), without reference to a local intermediary payer. At whatever level of government, I shall refer to the disburser of funds as the payer, whether the payment is made to a lower tier of government or to a provider. The payer’s problem is to design a payment mechanism that secures its policy objectives. Flows other than C and D in the diagram are referred to only when they are material to this policy problem.

Under flow C, the recipient of funds is an intermediate tier of administration, acting as a local purchaser of services (for example, a local government, a housing association, a district health authority). Indeed, in the extreme, the recipient could be an individual, who receives cash (for example, the cash payments made to some social care users in the Netherlands) or a voucher (for example, university students in England) with which to purchase public services. Under flow D, the recipient of funds is a provider of services (for example, a university, a hospital, a social services day centre). The ownership of the provider is largely immaterial – it could be a for-profit commercial undertaking, a not-for-profit foundation, a stand-alone public organization, or a wholly owned part of the purchaser organization. However, when designing the funding mechanism, the payer may need to take account of the ownership of providers, and the market in which they operate.

1.3 Types of funding mechanism

Determining the level and distribution of local financial allocations is often very challenging for payers. First, it is a difficult technical exercise to determine where public money is best spent. Second, any funding mechanism introduces powerful incentives for local organizations, and it is important to ensure they are in line with the payer’s intentions. Third, the political ramifications of any geographical funding choice can be acute, particularly when parliamentary representatives are elected on a geographical basis. And finally, a national government requires reassurance that public expenditure is being spent locally in line with intentions, yet monitoring the effectiveness and efficiency of local spending is often a difficult undertaking.

There are numerous ways in which a payer could determine the allocation of public funds. At its crudest, the distribution could be based on political patronage, perhaps rewarding localities according to their political support in the past, or their importance for future elections. Although few payers would admit openly to engaging in such patronage, there is ample evidence to suggest that to some extent it informs many allocation systems that are supposedly nonpartisan. The US literature is replete with the practice of pork barrel politics, whereby certain parts of the federal budget are ‘earmarked’ for local projects in order to secure an acceptance in the legislature of the government’s budgetary proposals (Mueller, 2003).

Another approach in widespread use is to distribute public funds according to historical precedent. Politically, it has the great attraction that it minimizes disruption to existing public services, and avoids potentially large swings from year to year inherent in other allocation mechanisms. Its popularity is manifest in the way that more systematic approaches to distribution are frequently abated by ‘damping’ mechanisms that seek to reduce the magnitude of year-on-year financial losses and gains to localities. However, sole reliance on such methods would leave a payer hostage to history, and powerless to react to changed circumstances or to implement new policies.

A third possibility is to allocate funds according to bids submitted by localities, or to make allocations contingent on some measure of local performance. In principle, this approach has much to commend it. If undertaken properly, it could ensure that public funds were spent in line with national policy intentions, in a cost-effective manner. Its major weakness is that it usually entails large transaction costs, in the form of central scrutiny and policing, and the preparation of bids by localities. It also makes local budgets contingent on the quality of local management, and so may lead to large geographical inequalities. Moreover, even if funds are allocated with scrupulous probity, unsuccessful localities may nevertheless perceive that the allocations have been made according to patronage rather than the quality of bids, leading to a further potential for perceived unfairness.

Finally, financial allocations could be made according to how much localities actually spend. In many circumstances, this approach contradicts principles of good public finance, as it is likely to encourage spending in excess of efficient levels. However, it was in England, the basis for most nineteenth-century forms of central grants-in-aid from central to local government, and its continued importance can be observed in many systems of matching grants (Bennett, 1982).

In practice, most systems of financing local public service institutions use a mix of all four types of mechanism to allocate funds from central to local institutions. However, a fifth approach – allocation by mathematical formula – is increasingly becoming the favoured approach to determining local financial allocations. It can be defined in broad terms as the use of mechanical rules to determine the level of public funds a devolved organization should receive for delivering a specified public service. The next section expands on the concept of formula funding.

1.4 What is formula funding?

The essence of formula funding is that the payer specifies in advance mathematical rules that determine the magnitude of the funding received by a devolved entity in a certain period, and that there are no provisions to change the allocation rules after the budgetary period. The rules might be very simple (for example, a fixed amount of per capita funding per annum) or very complex (see the example in Box 1.1). They might also be to some extent augmented by other funding mechanisms (for example, additional specific grants from the national government, or local taxes). However, the overarching objective of formula funding is to contribute to the creation of a budget for the local entity with which it is expected to fulfil its duties, in the form of the provision or purchase of public services.

There are two broad approaches to formula funding, discussed in detail in Chapter 3. The first reimburses the local entity (local government or service provider) on the basis of some measure of local activity, typically a count of the number of service users. Such case payment mechanisms are widespread in education (counts of pupils) and health care (counts of patients), and they are especially relevant when an unambiguous indicator of a service user’s need for the service can be established. However, they can be vulnerable to perverse incentives to create unwarranted or inappropriate service utilization. Case payment methods give rise to a variable budget for the local entity, based on recorded activity.

The other approach to formula funding is to reimburse according to the expected level of local activity. Typically, this takes a measure of the size and characteristics of a locality’s population, and infers the expected level of local service expenditure without reference to actual local service use. Because these methods are based on population counts, they have become known as capitation funding methods. They circumvent some of the perverse incentives inherent in case payment, but their effectiveness depends on how successfully the payer can adjust the capitation payments to account for variations in population characteristics. This ‘risk adjustment’ problem forms the core of Chapter 5 on empirical methods. In general, capitation methods give rise to a fixed budget for the recipient of funds.

Whatever the chosen mechanism, four institutional aspects must be in place for formula funding to take effect in its purest form. First, the delivery of the public service must be to some extent devolved. At one extreme the devolved entities might still be very large governmental organizations, in the form, say, of the Chinese provinces (typical population of 100 million). At the other extreme, the devolved entities might be individual citizens in receipt of vouchers to spend on specified services. Whatever their form, the devolved entities are then responsible for using the funds they receive either to purchase or provide the intended public services, or to devolve the funding to more local institutions.

Box 1.1 Example of a funding formula: the calculation of Formula Spending Shares for Social Services for Older People, England, 2003/04

Basic amount

£337.77

Top-ups

AGE TOP-UP

HOUSEHOLD AND SUPPORTED RESIDENTS AGED 75 TO 84 divided by HOUSEHOLD AND SUPPORTED RESIDENTS AGED 65 AND OVER, rounded to 4 decimal places and multiplied by £324.35; plus HOUSEHOLD AND SUPPORTED RESIDENTS AGED 85 AND OVER divided by HOUSEHOLD AND SUPPORTED RESIDENTS AGED 65 AND OVER, rounded to 4 decimal places and multiplied by £1,093.92; minus £179.15

DEPRIVATION TOP-UP

£238.39 multiplied by PENSIONERS IN RE...