![]()

1 The puzzle of radical right electoral fortune in Central and Eastern Europe

Introductory remarks

The presence of radical right parties, as well as the influence of radical right ideology on public debates and mainstream policy agenda, continue to pose a serious challenge for Central and Eastern European democracies. While these phenomena are also visible in ‘the West’ (Carvalho 2013), in the last fifteen years Central and Eastern Europe has witnessed a particularly dynamic growth and multifaceted development of new radical right actors that were able to establish their ideology at the centre of mainstream party politics (see, e.g. Mudde 2007; Minkenberg 2013; Minkenberg 2015b).

In the 2007 election, Poland’s voters had just ended a two-year governmental coalition lead by the conservative Law and Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS) with the radical right League of Polish Families (Liga Polskich Rodzin, LPR) and the social-populist Self-defence Party (Samoobrona). The coalition was not only marked by scandals and internal conflicts, but also by the authoritarian programme of the ‘Fourth Republic’ (PiS 2005). This PiS manifesto of so-called ‘national renewal’ included, among other specifics, state restructuring measures with regard to educational or morality policies, as well as political discourse that aimed to redefine Polish society along traditionalist and fundamentalist-Catholic notions (see in detail Pankowski 2010; cf. Kasprowicz 2015). In the early elections of 2007, the LPR dropped out of Parliament, and has not re-entered since. According to a PBS GDA exit poll, most of the party’s voters were accommodated by PiS. The party of J. Kaczyński managed to take over 413,000, or 43.9 per cent of voters that cast their ballot for the LPR in 2005 (Pacewicz 2007).

Some time later, extensive debates on the rights of the Hungarian minority erupted in Slovakia. The discussion was part of nativist historical and minority politics of the 2006–2010 coalition government led by Robert Fico’s social-populist Smer, Ján Slota’s Slovak National Party (Slovenská národná strana, SNS), and Vladimír Mečiar’s Movement for a Democratic Slovakia (L’udová strana – Hnutie za demokratické Slovensko, HZDS). A prime example of this policy reorientation was the 2009 amendment of the Slovak law on state language. The amendment has been internationally criticized for limiting the rights of ethnic minorities to official, public use of minority languages and imposed high fines for breaking the law’s provisions. The coalition ended in 2010 and the marginalized SNS found itself on the brink of parliamentary representation. According to a MVK exit poll, 25 per cent of voters who had previously supported SNS cast their vote for Smer in 2010 (Deegan-Krause 2010). Not long thereafter, following the early elections in 2012, the SNS dropped out of the Slovak Parliament.

But the most dynamic development in relation to radical right electoral fortune took place in Hungary. Up to 2009, only the Party of Hungarian Justice and Life (Magyar Igazság és Élet Pártja, MIÉP) had managed to enter the Hungarian Parliament, doing so in 1998. Nonetheless, MIÉP had vanished again by 2002, ousted by the growing dominance of the national-conservative Fidesz party led by Viktor Orbán. However, since 2007 the Hungarian Guard (Magyar Gárda), an anti-Roma, nationalist and irredentist militia movement has gained both high street visibility and international attention. In 2009, the party behind the Guard, the Movement for a Better Hungary (Jobbik Magyarországért Mozgalom, Jobbik), achieved groundbreaking success in the European parliamentary elections and in the national election the following year. Shortly before the 2010 elections, a survey by Medián showed that the biggest share of Jobbik voters came from Fidesz (37 per cent), followed by a large proportion of first-time (13 per cent) and non-voters (20 per cent) (Medián 2010). After 2010, in the wake of a landslide majority victory of Fidesz, Hungarian politics witnessed an ‘illiberal turn’ (Jenne and Mudde 2012) towards the right. The growing nationalist mood, anti-Roma demonstrations, and violence of radical right movements were accompanied by growing nationalist political discourse and legislation implemented by the Fidesz government. One example was the historically burdened debate over the introduction of dual citizenship for the Hungarian diaspora that caused severe protests among Hungary’s neighbour countries. Another one was the debate on Hungary’s Roma minority, fuelled by Jobbik’s anti-Roma politics and the party’s discriminatory narrative of ‘Gypsy crime’.

The puzzle of radical right electoral fortune

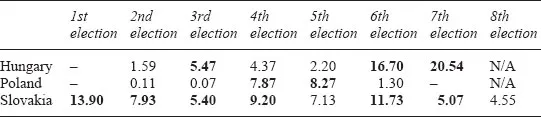

The examples above form the best cases for investigating radical right political agency and electoral trajectories in Central and Eastern Europe. The first observation is that, contrary to popular belief, radical right parties in Central and Eastern European democracies do not experience stable high electoral fortune (see Minkenberg 2015a). As Table 1.1 shows, it seems rather that ‘radical right parties come and go’ (Minkenberg and Pytlas 2012: 206). In fact, the radical right’s success at the polling booth is much less stable than in many West European countries such as Denmark, Austria, the Netherlands, or Switzerland.

The second observation is that, despite these unstable results, the widespread influence of radical right ideology on public discourse, policies, and positions of mainstream parties is clearly and continuously visible in the region. In general, the radical right’s impact on the political process can be identified on several levels, among other things in relation to public opinion, political discourse, party competition, policy-making, as well as counter-mobilization (Minkenberg 2002a: 266; cf. Minkenberg 2015a). The influence that radical right parties exert on liberal democracies – especially where it concerns immigration policies – can also be observed in Western Europe. Research, even if it is still on the starting blocks, has noted the growing influence of the radical right on Western European party systems, mostly in terms of spatial shifts and agenda co-optation by the mainstream (e.g. Schain 1987, 2006; Harmel and Svåsand 1997; Downs 2001, 2012; Minkenberg 2001, 2002a; Bale 2003; Heinisch 2003; van der Brug et al. 2005; Williams 2006; Mudde 2007: 241–2; van Spanje 2010; Akkerman 2012; Akkerman and de Lange 2012; de Lange 2012; Minkenberg 2013). Nonetheless, in Central and Eastern Europe, nationalism-oriented parties seem to be accepted in a much more straightforward fashion as potential coalition partners and legitimate participants in the political discourse (cf. Mudde 2000: 45; Minkenberg 2015a). In addition, mainstream political parties of the region adopt radical right ideology much more easily than in the West (Mudde 2005: 281; Minkenberg 2006: 29; Bustikova and Kitschelt 2009). The cases of Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia outlined above also point to the fact that mainstream parties and the radical right engage in competition over voters to a significant extent, albeit with varying outcomes.

Table 1.1 Results of radical right parties in parliamentary elections in Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia

Sources: Data from respective national electoral commissions.

Legend

Hungary – Magyar Igazság és Élet Pártja, Jobbik Magyarországért Mozgalom; Poland – Liga Polskich Rodzin, Narodowe Odrodzenie Polski, Polska Partia Narodowa; Slovakia – Slovenská národná strana, Pravá Slovenská národná strana, Slovenská národná jednota; Numbers in bold represent the successful entry of a radical right party into Parliament.

Why therefore, despite high discursive radical right influence on public debates and mainstream policy agenda, do radical right parties in Central and Eastern Europe not enjoy stable and high electoral success? This puzzle forces us to reconsider prior explanatory approaches towards radical right electoral fortune in the region. At the same time, it invites us to broaden our perspective towards discursive strategies of mainstream parties. For there seems to be a trade-off between electoral fortune and party competition in that ‘the electoral weakness of the radical right may have been bought at the price of much larger, more mainstream, “near radical right” parties that command substantial support in most of the formerly national-accommodative communist countries’ (Bustikova and Kitschelt 2009: 470).

This is the argument this book will explore in depth. With regard to the radical right’s electoral fortune, mainstream parties matter. They matter as their strategies of party competition constitute factors that influence and shape the political and discursive opportunity structures in which radical right actors are able to exercise their political agency.1 In regard to these strategies it is nonetheless important to focus not only on spatial, but also on narrative dimensions of party competition. This rather overlooked differentiation is crucial, because in order to fully explain the influence of competing party strategies on electoral results, one is required to look beyond which issues are contested, or in which direction particular strategies are deployed. Instead, it is also vital to explore the how of party competition, meaning the specific ways these issues are interpreted and framed. By looking at contests to gain ownership over radical right frames, this book proposes a further, narrative perspective on the study of party competition. It therefore aims to look at the interaction between the discursive influence of radical right frames, mainstream party competition over these narratives, and the consequences of these contests on the electoral success and failure of radical right parties in Central and Eastern Europe. The remainder of this introductory chapter will outline the basic tenets of this approach.

Value wars and pathological normalcy: the radical right in the Central and Eastern European context

The emergence and development of right-wing radicalism in Central and Eastern Europe has produced a series of more or less explicit explanatory clichés. Early scholarly approaches depicted the radical right as a ‘normal pathology’ of West European democracies (Scheuch and Klingemann 1967: 18). This paradigm saw ultra-nationalist parties and movements as an extraordinary, crisis-related phenomenon emerging under extreme conditions at the fringes of established, consolidated capitalist democracies. In the case of Central and Eastern Europe, the ‘normal pathology’ thesis was applied inversely, interpreting ‘extreme conditions’ as political normality in the new post-communist democracies. Hence, scholarship on this region often interpreted any high electoral results of radical right parties as an immanent part of the unconsolidated, economically weak democracies with their respectively inexperienced, disenchanted civil societies (e.g. Ramet 1999; Bayer 2002; Thieme 2007). In some cases this assumption turned into a vicious circle between cause and effect: on the one hand, the success of radical right parties was seen to hinder democratic consolidation and, on the other, the lack of democratic consolidation was given as the main explanation for the high electoral success of the radical right. Right-wing radicalism in Central and Eastern Europe therefore needs to be approached with caution, as a modern and modernization-related phenomenon similar to its occurrences in the West, that at the same time is embedded in a specific socio-cultural context (Minkenberg 2002b: 336). As a parallel to the Western shift towards a post-modern, or post-industrial society (Ignazi 1992, 2003; Betz 1994; Kitschelt and McGann 1995; Minkenberg 1998, 2000; Bornschier 2010), the emergence of modern right-wing radicalism in Central and Eastern Europe is related to processes of post-communist modernization. This societal shift was the effect of a democratization wave that swept across the region in the course of the ‘Autumn of Nations’ of 1989–91. The fall of the Iron Curtain should be seen not only as resulting in economic transformation to market capitalism, but also as a specific readjustment of the political system: the creation of pluralist, democratic state institutions and party systems under the circumstances of the collapse of old regimes and unfamiliarity with the new order (Beichelt and Minkenberg 2002). In the sphere of culture one can in addition observe phenomena of growing societal axiological pluralization and liberalization. Post-communist transformation was thus ‘more far-reaching, deeper and complex than the current modernization process in the West’ (Beichelt and Minkenberg 2002: 5–6).

Therefore, even if they are of a different nature, both processes were congruent in relation to the functional differentiation (Rucht 1994) of societies. The impact of the economic shift from controlled to free-market economy had had an immense effect on economic security and social welfare (Elster et al. 1998; Wagener 2010; Turley and Luke 2011). This resulted in the emergence of the vast strata of disenchanted ‘modernization losers’, unable to cope with the encompassing modernization shifts, and traditionally seen as prone to the radical right protest vote (for Western Europe see Betz 1994). Yet, radical right electoral fortune cannot be linearly traced back to modernization grievances or democracy inexperience alone. Modernization-related economic grievances certainly should not be disregarded as a contextual factor of radical right success. But with no visible trend dependent on national modernization paths, radical right parties seem to fail or succeed fairly independently of economic conditions, level of public support for democracy, or the state of democratic consolidation (cf. Mudde 2007; Blokker 2005a). This has been the case for the LPR in Poland. The SNS also enjoyed their success at times of economic prosperity, as Slovakia went from being the ‘sick man of Europe’ to the ‘Tatra Tiger’. Yet, the SNS exited the Slovak Parliament in 2012 in the wake of a financial crisis. In Hungary, after the varying electoral fortune of MIÉP, Jobbik also struggled before their initial success. The radical right entered Parliament despite the fact that after 2006 almost all Hungarian opposition parties pursued a crisis-oriented and anti-government rhetoric. Furthermore, in 2010 Jobbik acquired its voters mostly from the youngest, best-educated cohort rather than from classical ‘modernization losers’ (Karácsony and Róna 2011).

In the sphere of politics, scholarship has traditionally focused on the state and extent of institutional consolidation of Central and Eastern European democracies (Merkel and Sandschneider 1997; Beichelt 2001; Berglund et al. 2001). One of the central aspects of this approach was a focus on the fragmented, volatile, and fluid party systems with lacking party loyalties that had emerged as a result of the post-communist turn from single-party rule to a pluralist democracy (von Beyme 1996; Crawford and Lijphart 1995; Rose 2010). Yet, this development does not mean that ballots cast for the radical right can be understood primarily as a disenchanted protest vote or a class vote of strata associated with economic ‘losers of modernization’. On the contrary: as a result of weak party bonds, both programmatic value and issue voting (Kitschelt 1995; Miller and White 1998; Kitschelt et al. 1999; Shabad and Słomczyński 1999; Evans and Whitefield 2000; Rohrschneider and Whitefield 2009; Rudi 2010; Walczak et al. 2012) became much more w...