This is a test

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Core Theory in Economics

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

An important tenet of game theory, core theory has nonetheless been all but ignored by the mainstream. Its basic premise is that individuals band together in order to promote their interests as much as possible. The return to an individual depends on competition among various coalitions for its membership, and a group of people can obtain a joint maximum by suitable coordinated actions.

In this key title, Lester Telser investigates the following issues:

- Markets

- Multiproduct Industry Total Cost Functions with Avoidable Costs

- Critical Analyses of Noncooperative Equilibria.

Through these distinct sections, Telser skilfully brings the ideas of core theory to bear on a range of issues within economics – with particular emphasis on supply and demand and the way markets function.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Core Theory in Economics by Lester Telser in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Part I

Introduction

1 Prologue

We are faced at every turn with the problems of Organic Unity, of Discreteness, of Discontinuity – the whole is not equal to the sum of the parts, comparisons of quantity fail us, small changes produce large effects, the assumptions of a uniform and homogeneous continuum are not satisfied.

(John Maynard Keynes (1951, pp. 232–3))

What advances and what retards the wealth of nations remains the focus of economics. While gathering facts should not be demeaned, the guidance of theory is indispensable. It is my view that the theory of the core provides the most useful framework for studying an economy. It begins with the assumption that people try to arrange their economic affairs as well as possible. To this end they combine in coalitions. Within a coalition there is cooperation but among coalitions there is rivalry. Coalitions compete for members by means of the inducements they offer those who join them. Different coalitions form for different purposes. Therefore individuals may belong simultaneously to many coalitions. The freedom to form coalitions and the freedom to join them is essential for competition, but this freedom can be excessive so that no stable outcome can emerge. Property rights illustrate restrictions on freedom that enable stable and efficient outcomes. Applications of core theory to concrete situations can show what kind of freedom is compatible with the goal of advancing the wealth of a nation. It must never be forgotten that Robinson Crusoe economics is no t the proper study of economics. The whole economy is the proper study.

These chapters present a variety of applications of core theory to the main subjects of economics, calculation of demand, supply and their interaction in markets. The standard economic model evades many difficulties by making certain simplifying assumptions about the nature of supply and demand that are more appealing by virtue of their mathematical convenience than for their relevance to the actual economy. I propose to face squarely some of these difficulties and to provide some solutions for them. My goal is to gather into the domain of economics a broader swath of true economic problems. The result is better understanding of economic issues ignored by the standard model.

Combinatorial analysis is necessary for several topics falling into the realm of core theory. My applications of combinatorial analysis to economic problems employ binary programs (BP). Almost all of these are variations on a single theme – a systematic change of a strategic parameter with a view to forcing an accompanying continuous variable in the closed interval [0, 1] to an endpoint of this interval. This converts the continuous variable into a binary variable and thereby solves combinatorial problems. The key to success is careful analysis of each economic application with suitable constraints. Each BP is an algorithm constructing a sequence of linear programs to solve the binary problem. While this accurately describes the main idea, it must be qualified by the recognition that each economic application requires its own suitably tailored collection of constraints. Neither I nor anyone else has a general recipe for success in binary programming.

The usual model of the supply conditions assumes cost is a continuously increasing, convex function of outputs. It handles fixed costs by forming two categories of inputs, those that can vary continuously with the desired outputs and those that cannot. The latter are the capital inputs available to accommodate the demand forthcoming now and in the future. Hence the capital inputs depend on longer term views about demand conditions. In this model the long run cost function is often said to display constant returns to scale, but, because the capital inputs are fixed, the short run cost function exhibits decreasing returns – whence long run supply curves are infinitely elastic, but short run supply curves are not; they are upward sloping. In the standard model while demand varies randomly around the anticipated level, prices always equal marginal cost and can clear the markets. In the standard model average profits indicate whether capacity is too high, too low or just right. Given the standard model’s assumptions about the cost conditions, when average profits are positive, there is entry, capacity increases and profits fall; when average profits are negative so there are losses, capacity decreases, there is exit, losses decrease and profits can eventually emerge. The total capacity is just right when average profits are zero. An industry total cost function homogeneous of degree one implies that firm size does not matter so that infinitesimally small firms can operate on equal terms with a galactically large firm, and, also, for any size in between. However, the world is not kind to the standard model. Attempts to save appearances by supposing a minimally efficient size and constant returns above the minimal size are neither consistent nor realistic. Without constant returns to scale and without convex preference sets, the best models of general equilibrium are useless.

The leading position of constant returns to scale in the standard model is an old story. Sraffa (1960) says,

The temptation to presuppose constant returns is not entirely fanciful. It was experienced by the author himself when he started on these studies many years ago – and it led him in 1925 into an attempt to argue that only the case of constant returns was generally consistent with the premises of economic theory. And what is more, when in 1928 Lord Keynes read a draft of the opening positions of this paper, he recommended that, if constant returns were not to be assumed, an emphatic warning to that effect should be given.

(p. vi)

Be advised, then, in accordance with the advice of Lord Keynes, that I do not assume constant returns to scale.

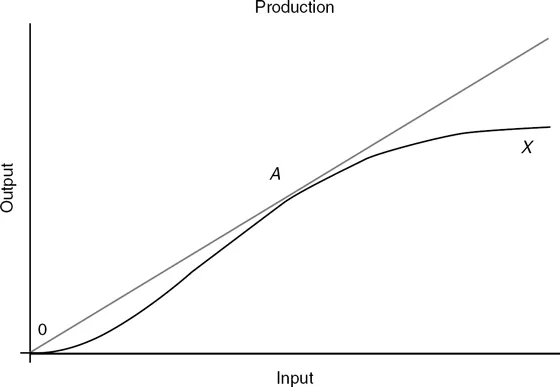

Figure 1 shows a typical production curve in which decreasing returns follow an initial interval of increasing returns. The graph of output as a function of input has an inflection point at A where the curve changes shape from convex to concave. Production functions with these properties always create combinatorial problems because the optimal outputs are never inside regions where the output is a convex function of the input. They are either at the boundaries of these regions or in the regions where the function is concave. The simplest approximation to this situation defines output, y, as a function of input, x, as follows:

Figure 1

y = 0 if x = 0 and y = a if 0 < x.

The initial convex piece thereby collapses to a jump in the approximating step function. A closer approximation represents the initial convex segment by setting a lower bound on the required input such that

y = 0 if 0 ≤ x ≤ b and y = a if b < x.

The essays on pure exchange employ valuation functions formally equivalent to production functions. These are step-wise approximations to the traders’ valuation functions cognizant that the underlying continuous functions would always raise combinatorial problems because the solutions are almost always at boundaries of the feasible sets.

Figure 2 shows a cost curve. As we would anticipate by analogy with the graph for the production function, the initial concave segment for a cost curve is followed by an unboundedly increasing convex curve. The inflection point A is the boundary between them. The simplest approximation to this case follows:

Figure 2

C = 0 if x = 0, C = a if 0 < x ≤ b and C = ∞ if b < x.

The term a is called the avoidable cost because the firm can avoid it by producing nothing. The chapters deriving the best industry response to the demand conditions assume company specific and commodity specific avoidable costs. The former are positive when the company is an active producer of at least one commodity and the latter are positive when the company actively produces a particular commodity.

I generally use the term “model” not “theory.” Theory uses an if-then approach that purports to deduce consequences from its postulates. A model is different. A model refers to a reality too complex to understand completely. It purports to describe some, never all, aspects of this reality. It is designed as a manageable work...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Part I: Introduction

- Part II: Markets

- Part III: Multiproduct industry total cost functions with avoidable costs

- Part IV: Critical analyses of noncooperative equilibria

- Bibliography

- Index