- 212 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This volume is the first full-length biography of Jean-Baptiste Say (1767-1832), the most famous French classical economist. During his lifetime Say actively took part in three revolutions: the French Revolution, the Industrial Revolution and the establishment of economics as an academic discipline. He struggled with Bonaparte, was the owner of a cotton spinning mill, and published his famous Treatise of political economy and many other economic writings.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 | Youthful revolutionary |

Early youth

Jean-Baptiste Say was born in Lyon on 5 January 1767, the oldest child of a Huguenot family. This Protestant lineage was one of the formative elements of his life. In his early career as well as in later life he was often in the company of other Huguenots and Calvinists. After the revocation of the Nantes Edict in 1685, his great-grandfather Louis Say had found refuge in Amsterdam where he took the oath as a citizen. He was a member of the Église Wallonne and had a very modest account at the Amsterdam bank of exchange. His Amsterdam merchant’s passport is still in the possession of his descendants. Jean-Baptiste’s son Horace Say, in his introduction of 1834 to his father’s Oeuvres Diverses, still wrote about the basket kept by the family in which Louis Say had carried his belongings to Holland, but it has not survived since.

By 1694 Louis had already moved to Geneva, where his son Jean became a registered citizen. This gave his descendants the right to call themselves citoyen de Genève, which continued after Jean’s son Jean-Estienne Say, the father of Jean-Baptiste, moved to Lyon. Louis and Jean Say were merchants of woollen and serge cloth, Jean-Estienne primarily traded in silk. For some time the latter kept a little diary in which he noted the registration of his children as Genevan citizens. He did not explicitly mention this with regard to his oldest, but Larousse’s Grand Dictionnaire Universel du XIXe Siècle even (wrongly) classifies J.-B. Say with Rousseau, Necker and Sismondi as born in Geneva. Still one century later Sismondi and Say could address each other as ‘Cher concitoyen’ in their correspondence. There were regular childhood family visits to Geneva which as late as 1814, when he walked on British cobblestones, revived Say’s boyhood memories of the Protestant capital’s pavement.1

Genevan family relationships were to remain an important factor in Say’s life and career. His mother was Françoise Castanet, whose parents were Honoré Castanet and Elisabeth Rath. Say’s younger brother Honoré, called Horace, was named after his grandfather; he married his full cousin Alphonsine Delaroche, the daughter of Daniel Delaroche and his mother’s sister Marie Castanet. Doctor Daniel Delaroche (1743–1812), a remarkable medic and botanist, was born in Geneva, studied abroad and finally settled in Paris. Members of the Castanet, Rath and Delaroche families were lifelong close relations, correspondents and sometimes business contacts of Jean-Baptiste. Other Genevan families figuring prominently in his life were the Duvoisins and Dumérils; after the death in action during Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign of Horace Say, his widow Alphonsine Delaroche married Constant Duméril. Jean-Baptiste’s aunt Duvoisin, née Say (his father’s sister), was to be a financier for his cotton mill which he started in 1804. She clearly cared about her nephews, as she wrote to the Genevan physicist Georges-Louis le Sage (who gave private lessons of mathematics) in 1786 about the education of her little nephew Horace.2

In his diary, Say’s father Jean-Estienne wrote very frankly about his family planning. This is worth noting by itself, and even more so because of his son’s future Malthusian notions. Among demographers Geneva is known as a clear example of eighteenth century birth control practice. The French historian Flandrin writes about the introduction of ‘coïtus interruptus’, specifying that

demographers see proof of the diffusion of this practice among the elites in the fact that as from the beginning of the eighteenth century the legitimate birthrate of the French nobility and of the citizens of Geneva has very notably lowered.

He even calls this the beginning of the Malthusian revolution.3

Jean-Estienne and his wife had planned to have two children. But after Jean-Baptiste and Denis (1768) an unplanned third one announced itself in 1770. Jean-Estienne wrote that he could live with the idea of having a daughter, but another son was born: Jean-Honoré, called Horace. Three days later, Denis died. Another son, Louis Auguste, was born in 1774. Because of his mother’s complicated pregnancies Jean-Baptiste – or simply Say, as his father called him in his diary – was sent to Genevan relatives for almost that entire year. On 30 June his father wrote: ‘Say has started his writing lessons with Mr. Borde.’ In the only completed chapter of his autobiography, Say mentions receiving lessons in physics at an early age – possibly from le Sage.

New Enlightenment insights on education and teaching did not go by unnoticed to the Say family. Say’s mother was the author of a manuscript called ‘Projet d’Education Nationale’, and Horace wrote another, called ‘De l’Education’. He also published a pamphlet under the title ‘Plan d’Education dans les principes de J.J. Rousseau’, in which he writes that he was brought up according to those principles. And he unfolds a plan for a boys’ boarding school to be situated near Paris, led by himself. It is unknown whether it received any acclaim, but it is not unlikely that this was the same project which Jean-Baptiste and his wife Julie considered establishing, after their marriage in May 1793 (see Figure 1.1). Horace’s choice for a military career might have been an obstacle to its execution, although both Jean-Baptiste and Horace would publish on the subject of education in La Décade. Teaching and education remained lifelong interests to Jean-Baptiste.

Figure 1.1 Jacques-Augustin-Catherine Pajou (1766–1828) served with the ‘sous-lieutenant’ Say in the Parisian ‘Arts Company’ in the campaign of 1792, under captain (and sculptor) Lemercier. He painted Say’s pair of marriage portraits in 1793. From the collection of Dominique Raoul-Duval (all rights reserved).

At the age of nine, he was sent to a boarding school run by a French priest and an Italian layman. Although precisely at that time the archbishop of Lyon strengthened his grip on the schools in the region, for fear of the ‘esprit philosophique’ of the century, Say’s overall recollections of the teaching and atmosphere were positive, with an exception for the endless hours of prayer on his knees. By contrast to the ‘fable convenue’ of the contemporary schoolbooks, he wrote that ‘grammar and the Italian language were taught quite well, and Latin pretty badly. Like Jean Jacques Rousseau I could say that I was destined to learn Latin all my life, and to never really master it.’4

Say’s father exported silk to European countries, and even to Turkey. When business was slack at the end of the 1770s, ‘his debtors were dispersed all over Europe, and his creditors at his front door’, as his son noted.5 He went bankrupt and the family moved to Paris in 1780, where Jean-Estienne managed to re-establish his credit as a currency broker. His son Jean-Baptiste became a bank clerk at the age of fifteen with the firm of Laval and Wilfelsheim, and later with Louis Julien.6 Eighteen years old, at the end of 1785, he was sent to England, together with his dear brother Horace, aged fourteen.

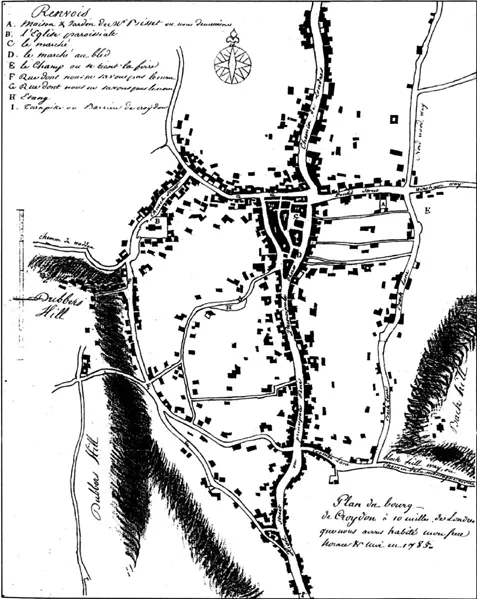

During this stay in London he resided in Croydon, where he worked for the trading company of James Bayle & Co., doing business with the Antilles, and later for Samuel & William Hilbert, trading with India.7 He became well versed in English and caught his first glimpses of the Industrial Revolution. Both assets would later be extremely valuable to his career. His first theoretical economic notions were traced back by him to observations made in Croydon. There they were lodged in a fairly new house where one day a mason came in to fill up an entire window with bricks, as a new law levied a tax on the number of windows. So the owner suffered ‘one enjoyment less’ while the treasury gained nothing. At the end of his life, Say was to write an entire chapter in the Cours Complet about taxes that do not produce any fiscal revenues, without however mentioning the Croydon case again.8 In the archives of the Borough of Croydon, the oldest map of the village kept there was drawn by J.-B. Say (see Figure 1.2).

Youthful revolutionary

At his return to Paris in 1787, Say became secretary to Clavière, like himself a man of Genevan Protestant stock. Etienne Clavière (1735–1793) was one generation older than Say, and the first of many Genevan Protestants who would play a role in Say’s career. He was a clever financier and speculator, but also bridged the gap with literature and politics. With Mirabeau, Lafayette and others he founded the Society of Friends of the Blacks in 1788.9 In that year he also became the director of a life insurance company. After the revolution he was one of the founders of the assignats system – where he was in the company of Say’s father Jean-Estienne – and was also suspected of forging false assignats. Twice a finance minister, he was arrested with other Girondins in 1793 and found guilty of channelling funds away from the insurance company as well as from the treasury to emigrants abroad, who had fled from France since the Revolution.

Next to his directorship of the insurance company, Clavière was at least as active as a pamphleteer and pre-revolutionary activist. He went further than Turgot and Necker in proposing radical reforms for France: politically by advocating the general male franchise; economically by pleading against the prominent role of the nobility, which he believed stood in the way of a commercial society, and in favour of simple tastes and of public credit. So he took up clear positions on topics that were hotly debated at the time and would continue to be so during the first ten years of the Revolution period. Say’s economic rejection of luxury and his plea for simplicity can to some extent be traced back to his first boss. These themes would recur in his Décade articles, in Olbie (1800) and in his later writings.

Whatmore writes about the evolution of the ideas of Clavière and his companion Brissot, from justifying popular sovereignty in small states to pleading a republican constitution for France. This was a truly revolutionary idea, as for most political and economic reformers the concept of France as a kingdom had been unassailable. Rousseau’s ideas on the importance of virtuous popular manners for the development of a flourishing state were a guideline to them: ‘From 1785, Clavière, Brissot and other members of their circle made Rousseau’s idea of manners the linchpin of proposals to transform France into a different kind of republic: one whose merits Say would quickly be persuaded to support.’10 Egalitarianism, meaning the abolishment of the aristocracy in the first place, was another essential idea. Aristocracy and luxurious consumption belonged to the past, the future was to commercial activity and simple manners.

Figure 1.2 This happens to be the earliest map known of Croydon, drawn by the young J.-B. Say: ‘Plan of the Borough of Croydon where we have lived, my brother Horace and me, in 1785’. The brothers stayed with Mr Alexander Bisset on Pound Street. Courtesy of the Borough of Croydon (all rights reserved).

Clavière may have strengthened Say’s early republican beliefs. He has certainly influenced, or at least awakened, Say’s turning to economics by lending him his copy of the Wealth of Nations. Say immediately felt so inspired that he rapidly ordered his own copy of its fifth edition (1789). This three-volume edition has survived, with Say’s annotations on practically every page – summaries on top of the page, critical notes in the margin. It was donated by his grandson Léon Say to the Bibliothèque de l’Institut in Paris in 1888. We shall come back later to the content of the notes.

However, more grandiose events took place in 1789 than the printing of Smith’s fifth edition. The Estates-General were called to meet, and the young Say contributed to the stream of publications overflowing all of France on this occasion. At the age of twenty-two he wrote a pamphlet on the freedom of the press. In rhetorical language he proposed the institution of a tribunal that would represent La République des Lettres, and would perform as an ‘ideal nation’, to be a tribunal in case of abuse of this freedom: ‘There I will denounce the brutal libel, and will proudly ask for an explanation of what it contains against me, my family, my king and my country.’11 In his own copy he afterwards crossed out mon roi in heavy black ink. Also in this annotated copy he describes this early work as ‘quite mediocre’, seeking an excuse in his age and in the atmosphere of the epoch. And precisely as a reflection of the age it is an interesting first product of the young Say, not yet an economist, and already more than an economist as well. There is also some irony in the fact that in the three first decades of the next century he would himself encounter serious problems of censorship: as the author of the Traité d’Economie Politique, a second edition of which was prohibited by Bonaparte; as a contributor to the occasionally censored Censeur Européen; and as a Conservatoire professor under surveillance by the French secret police.

When we turn to the events of 1789, we do not find Say’s name among those of the ‘vainqueurs de la Bastille’. But he must have been on the spot pretty rapidly, at least soon enough to collect a souvenir: a leaf of a seventeenth century prisoner’s interrogation, marked in his son Horace’s handwriting as ‘a piece found by my father at the taking of the Bastille’.12 His employer Clavière joined the Legislative Assembly, and through him Say obtained a job with the younger Mirabeau’s Courrier de Provence.

Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, Count Mirabeau (1749–1791) was a colourful nobleman who had been elected to th...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 Youthful revolutionary

- 2 At the crossroads of literature, politics and economics

- 3 A dissident under the Consulate

- 4 Reluctant entrepreneur

- 5 A rentier in a depressed economy

- 6 Spying in Britain

- 7 A dissident under the Restauration

- 8 Late recognition

- 9 The final years

- 10 Among masters, peers and students

- 11 Alive after 200 years

- Notes

- Archival sources

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Jean-Baptiste Say by Evert Schoorl in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.