![]()

Starting in 2008 the Republic of Ireland1 experienced its deepest economic crisis. The severe recession caused by the property crash, insolvent banks and the Irish sovereign debt crisis and resulting in the bailout by the troika of the IMF, ECB and EU Commission has dominated economic commentary since. Yet the ‘elephant in the room’ in the seemingly endless debate on the scale of the fiscal adjustments required is from where over the next decade economic growth is going to originate? Clearly, the faster Ireland grows as an economy the more sustainable the debt. By investigating the sources of growth for the past five decades, the book contributes to our understanding of the growth prospects of the country in the medium to long term.

Ireland is a small country of 4.6 million inhabitants in one of the most prosperous regions of the world. Its economic record has consistently attracted international attention. In 1987, after more than a decade of underperformance, The Economist magazine referred to Ireland as ‘the poorest of the rich’ (1988). Ten years later, in the middle of the so-called Celtic Tiger boom the same magazine referred to it as ‘Europe’s shining light’ (1997). By the early 2000s Ireland had a level of per capita GDP that was second only to Luxembourg in the EU. There was considerable interest from emerging countries in Eastern Europe and elsewhere as to the cause of the Celtic Tiger. In 2004 The Economist ran the headline ‘the luck of the Irish’ (2004), which perhaps reflected the emerging view that Ireland’s formula for success may not be easily replicated. The recession after 2007 was the most sudden and severe in the history of the state. Between 2007 and 2011 Ireland experienced one of the most severe downturns of any industrial country (Honohan, 2010).

Despite the current crisis, from the vantage point of 1970 Ireland’s subsequent economic development has been transformative. In 1970 Irish living standards were 61 per cent of the UK level, its nearest neighbour and most important trading partner at the time. Irish exports were a mere 18 per cent of GDP and 25 per cent of the workforce were engaged in agriculture. Between 1970 and 2011, allowing for inflation, Irish living standards have risen by 158 per cent or 2.3 per cent per annum. In 2011, despite the recession, living standards were 74 per cent of the EU 15 average;2 exports were 103 per cent of Irish GDP; and only 5 per cent of Irish workers were in agricultural employment.3 More tellingly, over the last decades Ireland has been increasingly identified as one of the most successful destinations in the world for foreign direct investment. At the present time it hosts many of the world’s leading businesses, including Apple, Intel, Google and Pfizer. In 2010, 80 per cent of Irish exports were from foreign-owned businesses assisted by IDA Ireland,4 mostly of US origin (Barry and Bergin, 2012).

This book is about the economic development of Ireland since 1970. It offers a fresh narrative on the spectacular rise and fall of the so-called Celtic Tiger economy. Guided by the theoretical framework which proposes that economic development is driven by business development, the book articulates an original account of Ireland as a micro-state with a unique reliance on foreign direct investment. Its highly centralized government’s pre-disposition to lobbying, which has yielded some notable successes and failures internationally, has also coincided with undue influence from distributional coalitions inside the country which have periodically undermined growth and development. By uncovering the drivers of business competitiveness at the industry, regional and institutional levels, the book reveals a discerning account of Ireland’s highly distinctive economic development path and weighs up whether Ireland will return in the next decades to be a serial under-achiever or a high-performing EU state.

It is not possible to be discerning about the economic development of Ireland over the last five decades by relying exclusively on one theory. This is due to the necessity to inquire into a range of issues that will be shown to be important for an understanding of Ireland’s unique development trajectory over this period. These include the strong reliance on multi-nationals, the small size of the country and the way government functions. As a result, an eclectic mix of theories is invoked. Rather than using theory as prescription, the approach taken is to stand back and use it as an organizing framework in order to develop a narrative that is both perceptive and comprehensive. Along the way a range of theories is appealed to and, where possible, evidence from the testing of hypotheses associated with these theories is introduced in order to support the narrative. In addition, gaps in knowledge, resulting from a lack of evidence from investigating particular theories, are also identified.

The theoretical framework used draws on the works of leading thinkers, both contemporary and historic, in the area of economic development as it might relate to small countries. These include Porter (1990a), Schumpeter (1934), Solow (1956), Kuznets (1966) and Olson (1965). In terms of Irish economists, while there are many prominent contributors, the book is significantly influenced by the work of Kieran Kennedy, who was the lead author of the last comprehensive book on Irish economic development (Kennedy et al., 1988). The work has also drawn from a range of other economists, regional scientists and political scientists who have written about Ireland over the past 50 years.

This chapter first sets the scene by presenting the spectacular rise and fall of the Irish economy. It then outlines the theoretical framework that guides the book. Considering the process of economic development as hinging on business development suggests that in order to understand the performance of the country one needs to focus on the productivity of those businesses. This is influenced by sources internal to the business but also by the external environment in which they function. The next section briefly describes the method of inquiry followed. The chapter concludes with an overview of subsequent chapters.

The spectacular rise and fall of the Celtic Tiger economy

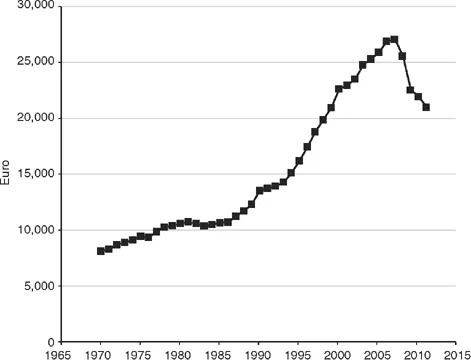

This book offers a fresh perspective on the spectacular rise and fall of the so-called Celtic Tiger economy. Figure 1.1 provides a telling picture of muted performance of Irish living standards in the two decades after 1970, followed by extraordinary growth beginning in the 1990s and culminating in a very sharp downturn post-2007. For reasons that are discussed in detail in Chapter 2, Irish living standards are best measured as per capita GNP. The decades of the 1970s and 1980s witnessed sustained relative underperformance, with Ireland failing to catch-up significantly in the EU. Between 1970 and 1990 per capita GNP only increased slightly from 65 per cent of the EU 15 average in 1970 to 67 per cent in 1990. This was followed by the remarkable Celtic Tiger period of the 1990s and the early 2000s, in which Irish living standards forged ahead to reach 91 per cent of the EU 15 average in 2007. The severe downturn since 2007 has been greater that other EU members, as witnessed by per capita adjusted GNP falling to 74 per cent of the EU 15 average in 2011.5

Figure 1.1 Irish per capita GNP: 1970–2011.

Note

Constant 2011 €. For the years 2009 to 2011, the adjustments by Fitzgerald (2013) are used to account for retained profits by foreign multinational headquarters.

It is clearly important to be consistent about the timing of the Celtic Tiger period. O’Grada (2002) timed the beginning at 1987, when GDP growth started its impressive rise, while Kennedy (2002) identified 1993 as the key year when total employment was back to its 1980 level. During the following decade and a half the term Celtic Tiger enjoyed widespread use. However, there are differences between the causes of Irish growth before and after 2002 (O’Leary, 2011). From the beginning of the Celtic Tiger to 2002 exports was the main driver of growth. This can be seen by the export share of GDP increasing from about 30 per cent in the late 1980s to 87 per cent in 2002. This was the era where Ireland became synonymous with high-technology exports by foreign multinationals. After 2002 the influence of exports lessened, with its share stabilizing. There was a loss of competitiveness fuelled by a bubble in the domestic property market. Between 2002 and 2007 growth was domestically driven. The bursting of the property bubble, combined with domestic fiscal and banking crises and the global financial and economic downturns since 2007, have spiralled Ireland into a major recession.

Therefore, for the purposes of the book the Celtic Tiger period is taken as 1993–2002. Between 1970 and 1993, Irish per capita GNP increased by 2.5 per cent per annum. This was followed in the Celtic Tiger period by acceleration to 5.7 per cent per annum. From 2002 to 2007, the period coinciding with domestically driven growth, per capita GNP increased at 2.9 per cent per annum followed by a contraction by 6.1 per cent per annum until 2011. Over the full 41-year period displayed in Figure 1.1, per capita GNP increased by an average of 2.3 per cent per annum.

Economic development as business development

The narrative developed in this book is concerned with the economic development of Ireland since 1970. It is guided by a perspective on economic development as it relates to advanced, small, outward-orientated nations. According to the IMF, which classifies economies as advanced or emerging and developing, Ireland is one of 34 advanced economies of the world (IMF, 2013).6 The Global Competitiveness Report includes Ireland as one of 35 innovation-driven economies, with a competitiveness ranking of 28th in 2013–14 (World Economic Forum, 2013). Its population of 4.6 million clearly places it as one of the smaller advanced nations in 2013 (IMF, 2013).7 Outward orientation refers to the extent to which Ireland’s economy is reliant on foreign trade. One measure of this is exports as a share of GDP, which is extremely high in Ireland, standing at 103 per cent in 2011.8

For the purposes of this book, economic development is defined as the wealth creation processes that bring about sustained national economic prosperity. National economic prosperity, which is the result of economic development, relates to the average income or living standards of citizens of a country, normally measured as per capita GDP. As will be seen in Chapter 2, Ireland is an exception due to the strong presence of foreign-assisted businesses, which nowadays necessitates using adjusted per capita GNP as the preferred measure. The level of average income is typically associated with the extent to which average citizens enjoy the benefits from the consumption of a range of private and public goods and services over their lifetime. These include access to health and education, which are often included as measures of development.9

Sustained prosperity refers to consistent increases in living standards which may be observed over long periods of time. From year to year there may be relatively large or small increases, or on occasion, decreases in average income. In the Irish case it is evident from Figure 1.1 that annual increases predominate. Indeed, this is the norm for the majority of countries. However, in six of the 41 years on display in Figure 1.1 average income in Ireland actually decreased on the previous year, a not untypical occurrence internationally. Changes in living standards therefore occur in cycles, characterized by consecutive years of relatively high growth or booms and consecutive years of relatively low and sometimes negative growth known as recessions. These cycles have no fixed length or frequency. They shape the evolution of a country’s prosperity over long periods. Therefore, sustained increases in living standards are best summarized by taking the average growth of per capita GNP over selected periods of years to coincide with booms and recessions.

The rest of this section considers the salient features of economic development that might be relevant to an understanding of the drivers of prosperity in a country like Ireland. These are productivity, structure, location, size and government. In each case the key insights that form the guiding theoretical framework are outlined. Well-documented patterns of economic development are presented. These stylized facts (Kaldor, 1957) are drawn from studies of large numbers of countries over many decades.

Productivity

The key driver of a country’s prosperity is its productivity (Solow, 1956; Porter, 1990a; 1990b; 1996). National productivity is the value of goods and services produced by resources employed. In generic terms resources include labour, capital equipment and knowledge. However, as such, countries are not the ultimate decision-makers on the use of private resources. This role is played by individual businesses, who in pursuit of objectives, such as profit, growth or survival – all of which are uncertain – decide on what resources to use and how to employ them. Of course, governments also play a key role, to be discussed later in this section, in directly supplying certain resources, in financing the supply of other resources and in regulating industries and markets.

The decision to employ resources in the expectation of creating value is made by entrepreneurs, who ultimately, according to Cantillon, writing in 1755, “buy at a certain price and sell at an uncertain price” (Thornton, 2010: 75). Entrepreneurs therefore play a key role in economic development. They initiate economic change by what Schumpeter referred to as “the carrying out of new combinations” (1934; 14th printing 2008: 65–66), such as the introduction of new products, entry into new markets, the introduction of new methods of production, new sources of supply or new ways of organization production. These are nowadays known as product and process innovation (OECD, 2005). The entrepreneurial function is therefore a special kind of resource that guides the process of economic development in a country.

The notion that national prosperity is driven by business has been central to the work of Michael Porter (2004: 31), who claimed that:

the productivity of a country is ultimately set by the productivity of its companies. An economy cannot be competitive unless companies operating there are competitive, whether they are domestic firms or subsidiaries of foreign companies … the sophistication and productivity of companies is inextricably intertwined with the quality of the national business environment.

Porter’s model of national competitiveness emphasizes not only the central role of business but also the environment in which business operates. His diamond or cluster theory introduced what he referred to as the micro-foundations of national competitiveness which support productivity growth through an emphasis on improvement and innovation by businesses. Porter’s (1990a) framework attributes a nation’s capacity to innovate to four determinants of competitive advantage, namely: factor conditions, demand conditions, related and supporting industries and the context of firm strategy, structure and rivalry. Figure 1.2 provides a visual picture of the framework. Also included is government, the role of which is addressed later in this section.

Factor conditions relate to human, capital and knowledge resources. These supply-side inputs have been central to the neoclassical and endogenous g...