![]()

PART II

Sexual Harassment in the Workplace

Now that a few women have the tools to address the legal system on its own terms, the law can begin to address women’s experience on women’s own terms.

—Catharine MacKinnon, Sexual

Harassment of Working Women

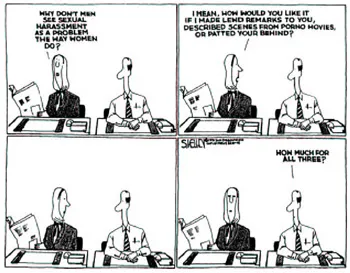

Reprinted by permission from Copley News Service and Steve Kelley

![]()

3

Men, Women, and Sex at Work

Is there such a thing, in life or in law, as reasonable people, or only men and women, with all their differences?

—Susan Estrich, “Rape”

The concept of a nongendered reasonable person is sometimes a non sequitur. The reasonable person assessing sex at work is a prime example. Psychology professors Barbara Gutek and Maureen O’Connor note that the prevalent view that men and women perceive sex in the workplace differently has “a basis in both common sense and empirical fact.” These gendered perceptions have real consequences. Social science research, such as that conducted by Weiner and his colleagues, confirms what common sense tell us: sexual conduct in the workplace that many men view as harmless and enjoyable, is experienced by many women as harmful and degrading. Because of this discrepancy, it is simply unrealistic to believe that a truly genderless standard can be used for determining whether conduct is sufficiently egregious to justify liability. In practice, when asked to assess the conduct of an actor accused of creating a hostile sexual environment, the decision maker will either explicitly (reasonable man or reasonable woman) or implicitly (reasonable person) adopt a gendered perspective.

The 1991 Senate confirmation hearings for Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas highlighted the different perspectives of men and women. The hearings presented the fundamental problem of how to convince decision makers (ninety-eight male and two female senators) that conduct which many women view as sexual harassment merits serious consequences for the harasser. In the case of Clarence Thomas, the stakes were extremely high: life tenure on the most powerful court in the country. Not only sex but also race and politics shaped the perspectives brought to the hearings. Nevertheless, the conduct that Anita Hill described exemplifies the fault line between men’s and women’s perspectives about what constitutes a hostile work environment. The hearings galvanized women around the issue of sexual harassment and gave new meaning to the phrase “they just don’t get it.”

Anita Hill testified before the all-male Senate Judiciary Committee, describing what happened to her while directly supervised by Clarence Thomas:

After approximately three months of working [at the Department of Education], he asked me to go out socially with him. What happened next and telling the world about it are the two most difficult … experiences of my life…. I declined the invitation to go out socially with him, and explained to him that I thought it would jeopardize … a very good working relationship. I had a normal social life with other men outside of the office…. He pressed me to justify my reasons for saying “no” to him….

My working relationship became even more strained when Judge Thomas began to use work situations to discuss sex. On these occasions, he would call me into his office for reports…. After a brief discussion of work, he would turn the conversation to a discussion of sexual matters. His conversations were very vivid.

On several occasions Thomas told me graphically of his own sexual prowess. Because I was extremely uncomfortable talking about sex with him at all, and particularly in such a graphic way, I told him that I did not want to talk about these subjects. I would also try to change the subject…. My efforts … were rarely successful.

Many of the senators hearing Hill’s testimony believed that the conduct she described was not and should not be actionable as sexual harassment or discrimination, even if she was telling the truth. Nor did they think it should interfere with Thomas’s confirmation. Senator John B. Breaux said, “I think the charges are not of a sufficient nature to either not support [Thomas] or delay the vote” (emphasis added). As Senator Paul Simon put it: “Many men were stunned to learn what women regard as sexual harassment. ‘He didn’t even touch her!’ one of my Senate colleagues commented … when the issue first arose.” Some of these reasonable men did not believe a reasonable person would have found that Thomas’s conduct created a hostile work environment. After all, it wouldn’t have felt like sexual harassment to them.

Polls indicated that at first, male or female, black or white, a majority of Americans didn’t believe Anita Hill’s version of “he said/she said.” This is not surprising; as Catharine MacKinnon in Feminism Unmodified points out, most people find it difficult to believe women’s “accounts of sexual use and abuse by men,” particularly by powerful men. Interestingly, a year after Thomas was confirmed as a member of the Supreme Court, polls showed that public perceptions had changed dramatically: more people believed Hill than Thomas. Setting aside the issue of credibility, if Anita Hill had brought a timely sexual harassment action against Clarence Thomas, and if she had been thought credible at the time, would any standard of care have assured that his conduct would be judged sufficiently severe and pervasive to constitute illegal sexual harassment? Only under a standard that explicitly considered female perspectives would Thomas’s conduct likely be viewed as sufficiently egregious to merit liability. Applying a reasonable woman standard, by requiring decision makers to consider how pressuring a subordinate for dates and subjecting her to graphic sexual stories is disrespectful and intimidating, enables them to comprehend the harm in such conduct.

The Evolution of Hostile Environment Sexual Harassment

Sexual harassment’s recent appearance and rapid development as a legal claim is more her-story than history. Men have sexually harassed women for thousands of years, but the conduct wasn’t given a name until 1975, when a group of feminists in Ithaca, New York held a meeting called “Speak-Out on Sexual Harassment.” It took years of concerted effort by feminist lawyers and clients to establish a legal identity and remedy for such conduct. The breakthrough came in 1976, when the federal circuit for the District of Columbia heard two cases about retaliation against a female employee for refusing her supervisor’s sexual advances. The court held in both cases that this was actionable sex discrimination under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act. Before these two pathbreaking decisions, punishing women workers who rejected sexual advances did not constitute employment discrimination on the basis of sex.

In 1979, Catharine MacKinnon published her influential book Sexual Harassment of Working Women, in which she defined sexual harassment as “the unwanted imposition of sexual requirements in the context of a relationship of unequal power.” In MacKinnon’s view, the power disparities between employer and employee and men and women lie at the core of sexual harassment. Her book treats sexual harassment as sex discrimination and outlines two basic forms: quid pro quo and hostile work environment. In the twenty years since MacKinnon’s book was published, courts around the world, including the U.S. Supreme Court, have adopted her views and categories concerning sexual harassment.

The courts first recognized quid pro quo sexual harassment, which involves sexual coercion related to the terms or conditions of employment: offering rewards for granting sexual favors or threatening punishment for refusal. In the breakthrough cases, the plaintiffs lost jobs or other tangible job benefits when they refused to submit to their supervisors’ sexual advances. After the first cases a consensus gradually arose, finding that quid pro quo harassment is unreasonable, harmful, and discriminatory. Thus, in most quid pro quo cases unreasonableness and injury are easily established, no matter which standard of care or whose point of view is adopted. In 1998 the U.S. Supreme Court decided Burlington Industries, Inc. v. Ellerth, holding that because tangible economic harm is involved, employer liability for quid pro quo sexual harassment is vicarious and strict—if the plaintiff proves quid pro quo sexual harassment, the employer is liable.

Courts took longer to recognize the more controversial hostile environment sexual harassment as a form of discrimination. Hostile environment sexual harassment is sex-based conduct that interferes with a person’s job performance, even if it has no tangible or economic job consequences, and even if the interference is unintentional. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in Harris v. Forklift Systems, Inc. has described this form of harassment simply as “discriminatory conduct [that makes] it more difficult to do the job.” It may involve purely sexual conduct (e.g., groping breasts or pressuring for dates) or purely sexist/antiwoman conduct (e.g., saying, “You’re a woman, what do you know”) but often involves both. As the reaction to Anita Hill’s allegations demonstrated, there is little consensus about what constitutes hostile environment sexual harassment. Therefore, unlike quid pro quo cases, perspective often controls the outcome.

Hostile environment sexual harassment did not emerge as a recognized claim until the early 1980s. Its status remained uncertain until 1986, when the Supreme Court’s first sexual harassment case, Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson, recognized hostile work environment as a form of sex discrimination. The Court noted that unwelcome sexualization of the work environment, as long as it was “sufficiently severe or pervasive ‘to alter the conditions of [the victim’s] employment and create an abusive working environment,’ is actionable sex discrimination” under Title VII. Furthermore, the Court noted that if the conduct has that effect, liability can be found even if the actor did not intend to sexually harass the victim.

The harassing conduct alleged in Meritor, which included multiple instances of rape, was clearly intentional and egregious. Once the Court recognized hostile work environment as a legal claim, the Meritor conduct created an obviously abusive work environment—under any standard. Consequently, the Court did not address whose perspective or what standard determines whether someone has “creat[ed] an intimidating, hostile, or offensive working environment,” or even what kind of injury must be proved.

However, most hostile work environment claims are not as clear-cut as Meritor. Usually, alleged harassers assert that they did not intend to sexually harass the target; plaintiffs respond that the behavior had the effect of creating a hostile environment, regardless of intent. In these cases, the standard of care applied often determines the outcome. The issue of whether the conduct was “sufficiently severe or pervasive” to make it unreasonable requires a normative assessment of severity and pervasiveness about which men and women may, and often do, differ.

The Supreme Court has continued to play a crucial role in the development of hostile environment sexual harassment. In 1993 the Court decided Harris v. Forklift Systems, Inc., which focused on what kind of harm must be shown. Harris is important in part because most of the abusive conduct at issue was sexist, not sexual. Much of the harassment women experience is not sexual as such but it is sex-based, which has tended to get lost in the common perception of what “sexual harassment” means. A better term for the discriminatory conduct would be sex-based harassment, as Professor Vicki Schultz sets out in her article “Reconceptualizing Sexual Harassment.” However, the Supreme Court continues to use the term sexual harassment, so we do too.

Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s opinion for the unanimous Court in Harris declared: “So long as the environment would reasonably be perceived, and is perceived, as hostile or abusive,… there is no need for it also to be psychologically injurious” (emphasis added). By making clear that neither tangible nor psychological harm was required, the Harris Court made the reasonableness of the conduct the critical issue. However, the Court was silent about whether reasonableness can be explicitly gendered.

The Court issued another unanimous decision, Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Services, Inc., in 1998, which appeared to endorse a standard of care that assesses the alleged harasser’s conduct from the perspective of the injured party. Justice Antonin Scalia, writing for the Court, held that male-on-male heterosexual sexual harassment creates a viable claim under Title VII if the plaintiff proves that the harassment occurred because of his sex. He noted that “the objective severity of harassment should be judged from the perspective of a reasonable person in the plaintiff’s position, considering ‘all the circumstances.’”

If the phrase “in the plaintiff’s position” includes gender as part of his or her position, or if gender is intended to be included by “all the circumstances,” then Justice Scalia’s standard might substantively equate to a reasonable man standard when the injured party is male and a reasonable woman standard when the injured party is female. This interpretation is especially plausible in light of his emphasis on the “because of such individual’s … sex” requirement in Title VII, and his additional statement that all sexual harassment cases require “careful consideration of the social context in which the particular behavior … is experienced by its target.”

That the Court might find a woman-based standard appropriate when the target in a hostile environment sexual harassment suit is female represents tremendous progress. However, we believe the law must go further to achieve equality and justice for all. As we elaborate in chapter 5, the reasonable woman standard should apply in all cases of hostile environment sexual harassment, regardless of the gender of either party.

Why Courts Should Adopt the Reasonable Woman Standard

Applying a reasonable woman standard in hostile environment sexual harassment cases alters expectations of both legal and employment decision makers about sexual and sexist conduct in the workplace. The more male dominated the workplace, the more expectations change. Through the reasonable woman standard, our legal system can better achieve its important goals, including reducing the harm people inflict on others, compensating those harmed, and achieving substantive equality for all Americans. For claims of sexual harassment, the reasonable woman standard is a better vehicle than other standards for achieving these goals.

Working women are sexually harassed far more often than working men, and men are far more likely to sexually harass other workers. In part this can be attributed to the tendency of men to view a wider range of women’s workplace behavior as sexual and welcoming, and therefore to assume they have permission to respond sexually. As psychology professor Barbara Gutek notes in Sex and the Workplace, “men [are] more likely than women to label any given behavior as sexual. Thus a normal business lunch seems to be labeled a ‘date’ by some men just because the luncheon partner is a woman.”

Another reason women are sexually harassed at work more often than men is that traditional views of masculinity encourage dominating conduct—the exercise of power over someone else—and men often use sex as a means of asserting dominance. This explains why, if there are no women in the workplace, other men may be sexualized—treated like women—despite all the parties asserting heterosexuality. As Catharine MacKinnon argued in a “friend of the court” (amicus) brief in Oncale, the 1998 Supreme Court case concerning a man who had been sexually assaulted by his all-male coworkers: “Oncale’s attackers were asserting male dominance through imposing sex on a man with less power. Men who are sexually assaulted are … feminized: made to serve the function and play the role customarily assigned to women as men’s social inferiors.”

In addition, men may sexually harass women more often because women’s typically subordinate positions in the workplace tend to sexualize them. According to the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, Henry Kissinger said that “power is the great aphrodisiac.” For some male supervisors, having power over a female employee makes her sexy. A 1995 study by John Bargh and colleagues entitled “Attractiveness of the Underling” indicated that for men whose values make them likely to sexually harass women, having power over a woman enhances the sexual attraction. The aphrodisiacal quality of power also affects these men’s perception: they interpret women subordinates’ neutral or merely friendly actions as flirtatious or seductive.

The sexual thrill of domination, rather than romantic feelings, frequently motivates a sexual harasser to abuse his power. As a rule, men possess social, organizational, and physical power over women. Thus, when people abuse power through sex, the person abused is usually a woman. For men, being supervised by a woman is a rare experience, while for women it is the norm to be supervised by a man. Even in such traditional “women’s” work as primary and middle-school teaching, principals and superintendents are usually men. In traditional “men’s” work, such as construction or engineering, supervisors are almost certainly male and often are openly contemptuous of women workers.

Vicki Schultz, in her article “Reconceptualizing Sexual Harassment,” provides another important reason why women are so frequently harassed in the workplace. In arguing that hostile environment should be viewed from a “competence-centered” paradigm, she asserts that harassment of women workers is not about sexuality as much as it is about “reclaim[ing] favored lines of work and work competence as masculine-identified turf—in the face of a threat posed by the presence of women (or lesser men) who seek to claim these prerogatives as their own.” Schultz notes that the stakes are high for men:

Motivated by both material considerations and equally powerful psychological ones, harassment provides a means for men to mark their jobs a male territory and to discourage any women who seek to enter. By keeping women in their place in the workplace, men secure superior status in the home, in the polity, and in the larger culture as well.

Women also suffer greater injury: they much more frequently lose their jobs or suffer other tangible work detriment as a result of sexual harassment. Studies of sexual harassment of men show that some sexual conduct that women find harmful men view as perhaps annoying but not upsetting. Expert witness Susan Fiske testified in Robinson v. Jacksonville Shipyards that “when sex comes into the workplace, women are profoundly affected … in their ability to do their jobs.” By contrast, Fiske notes that the effect of sexualization of the workplace is “vanishingly small” for men. According to Barbara Gutek in Sex and the Workplace, the men she surveyed reported “significantly more sexual touching than women” and were more likely “to view such encounters positively, to see them as fun and mutually entered.” Men apparently suffer no work-related consequences of sexual behavior at work, although they report more sexual behavior both directed at them specifically and in the workplace atmosphere generally. Even sexual conduct that does not meet the existing standards for sexual harassment lowers women’s job satisfaction, while it has little or no negative effect on men.

One reason for the gendered reactions to and experiences with sex in the workplace may be that women have more to fear from sex. In our society, women are usually the targets of sexual violence. Except in all-male environments—where some men are “treated like women”—it is women who are raped and sexually assaulted. Because sex can be dangerous for women, when a workplace becomes sexualized, women are more likely to feel discomfort, fear, humiliation, or anger.

Women also prefer to keep sex out of the workplac...