![]()

1

Truths That Are Not Self-Evident

The Revolution in Political Speech

One day during the last week of October 2010, as I was opening the mail, a political flyer caught my eye. Political mailings were no strangers that season. Nonetheless, even more than most voters during the Fall 2010 election cycle, residents of our small Ohio town had been bombarded. We had the full slate of candidates at every level except president; levies for the schools, the library, and local emergency services; and a referendum on anti-discrimination ordinances that attracted tens of thousands of dollars in out-of-state money and more letters to the editor of our local paper than any other issue in its century of publishing. Still, this flyer was striking. It featured a colorful shot of Mount Rushmore with an American flag in the foreground. “They,” that is, the honored presidents carved into South Dakota granite, “would expect you to vote” to “create Ohio jobs,” to “balance the budget,” to “provide taxpayers relief,” and to “stop government takeovers.” Finally, it implored its readers, “Don’t let them down!” The photo had been altered to highlight a sunlit George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Abraham Lincoln but cast Theodore Roosevelt in shadow—no need for the conservative group that financed the mailing to remind voters of the ambiguity of a Republican president who believed in a vigorous federal government. The whole thing seemed curious to me, especially considering Washington and Jefferson. Neither of them conceived that the government had any direct role in creating jobs. As president, Washington pursued policies that greatly increased the federal debt, rather than balancing the budget, and although the federal debt was reduced during Jefferson’s presidency, he was deeply criticized for the extravagance of the Louisiana Purchase. As a general, Washington bemoaned citizens’ reluctance to pay taxes to support the Continental Army; would he really want taxes cut now, as the nation was involved in two foreign wars? And how could anyone possibly divine the opinion of men who lived in an age of horses as to their position on the federal bailouts of General Motors and Chrysler? I don’t know the answers to these questions. No one does.

One thing I do know is that political parties and politicians do more than enlist the founders to serve their own political ends. They do so in markedly different ways, depending upon where they—the politicians, that is—stand on the political spectrum. This chapter maps the terrain of today’s politicized memory of the American Revolution to explore shared expressions, common themes, and ideological differences that have implications not only for how different Americans consider history but also for contemporary policy making, showing how the American Revolution continues to be contested ground. It does so by charting presidential campaign rhetoric, primarily from 2000 through 2012. During the 2008 presidential campaign, John McCain praised “our founding fathers,” who “were informed by the respect for human life and dignity that is the foundation of the Judeo-Christian tradition.” Conversely, Barack Obama spoke glowingly of “that band of patriots who declared in a Philadelphia hall the formation of a more perfect union.” Conservative candidates tend to invoke an essentialist view of the American Revolution. Would-be Republican presidents were often quick to mention the “Founding Fathers” (usually capitalized in official transcripts released by the candidates) and cite their wisdom to suggest that the founding generation, speaking with one voice, offered timeless, inviolable principles that apply directly to contemporary political issues. Essentialism assumes the imperative for a limited federal government and thus the illegitimacy of programs and policies that extend the federal government’s purview. Liberal candidates offered potential voters the chance to further “perfect the union” to realize the egalitarian ideals of the Revolution, thus espousing a more organicist view of history and the Revolution. Organicists understand the task of perfecting the union as one that requires new tools for changing political, economic, and social conditions—in ways organicists openly admit the founders would not have recognized. These differing views of the past have profound consequences.

To get a sense of the way the memory of the American Revolution has become politicized across the spectrum of historical expression—including politicians, public historians, scriptwriters and directors, judges and activists, biographers, and even historians—I begin with the most easily identifiable by ideology, choosing to analyze presidential campaign rhetoric. Nearly 250 years after the American Revolution, U.S. politicians still frequently refer to its words, its leaders, and its events, thereby acknowledging and further enshrining its place in national memory as continually contested and politicized. It gets invoked as the ultimate appeal to civic authority, as a challenge to live up to or exceed the founders’ vision, and in paeans to patriotism. But the possibilities and therefore the practical difficulties of getting a grip on what’s being said are nearly endless. Contemporary news is bathed in political rhetoric. Nearly every day, it seems, the president, 435 members of the House of Representatives, 100 senators, 50 governors, their aides, and all the people intending to vie for those offices are eager to speak, state, talk, and now even tweet. I decided to focus upon presidential campaigns, including both the party primaries and the general elections. Every four-year cycle, up to a dozen candidates hail from at least one of the two parties, and in elections with no incumbent, from both parties. The primary candidates cover the range of what we might call “mainstream” American political discourse. Because candidates are running for national office, they address broad themes, trying to communicate more than their positions on particular policies (sometimes to clarify, other times to artfully obfuscate). They want to convey a more general picture of their aspirations for public policy and for the nation. Their references to the American Revolution become particularly freighted with implications for how potential presidents would pursue policy in the Oval Office and how they believe their views match the nation’s voters.

Political polarization, and the partisanship that has come with it, has broadened markedly in recent decades; political scientists suggest that the United States may be more starkly divided now than at any time since the late nineteenth century. That’s not to say that Americans have not always been partisan; rather, political division has become measurably more intense. Admittedly, politicians, especially the ones who think of themselves as moderates, have bemoaned partisanship for decades. Lloyd Bentsen chalked up the failure of his 1976 bid for the Democratic presidential nomination to increased partisanship, which was easier than blaming his campaign’s lack of organization or his own lack of charisma. But by a variety of measures, partisanship has increased from the 1970s through the 2010s, especially in the 2000s. This accelerated division has occurred both among the people and our representatives, even in the Supreme Court. Casual and systematic observers have suggested many causes, among them the fracturing of the big three networks’ former media dominance, the prevalence of self-contained communities on the Internet, and the rise of ideological political spending outside of party control. Gerrymandering has been another widely perceived culprit, although examinations of redistricting as a source of political polarization suggests that Americans are also moving into communities of like-minded people. Since 2000, one would be hard-pressed to find any presidential primary candidate who was more ideologically in tune with the other party than with his or her own. That makes the use of presidential primary speeches an especially good source for considering the intersection between political ideology and interpretation of the American Revolution.

In order to be systematic in my analysis of presidential campaign speech, I began with speeches from the 1968 election. I therefore included speeches before and after the celebration of the nation’s bicentennial, just to see whether that massive celebration of the Revolution had any effect (it didn’t, as far as I could see). Only the speeches of the two major-party nominees after their official nominations from that contest through the 1996 election were readily available, but that was enough to give the overall study a sense of historical context. From the 2000–2012 elections, I was able to collect a large sample of the speeches and statements of all the Democratic and Republican presidential primary candidates. These speeches ranged in date from when the candidates declared their intention to run for president through when they dropped out or, in the cases of the party nominees, through Election Day. In self-identification, candidates ranged from the further ideological reaches of their party—like archconservatives Fred Thompson and Gary Bauer and ultraliberals Dennis Kucinich and George McGovern—to those attempting to position themselves as centrists—like Rudy Giuliani and Joe Lieberman (here I am using their general political and rhetorical positioning, not the way their opponents or supporters characterized them). Some candidates made their careers outside Washington, such as mogul Steve Forbes and Arkansas governor Bill Clinton, in contrast to longtime Washington hands like the former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich and Senator Joseph Biden. A few offered short political résumés, like Herman Cain, who had never even run for elective office, while others like Bill Richardson boasted long and varied political experience (Richardson has served as a governor, ambassador, member of Congress, and cabinet member). Given the realities of our two-party system, and that, in the most recent election cycles as in most in the nation’s history, there have been few extended third-party movements, I excluded third-party candidates.

As with any decision of what to research, the selection of presidential speeches held advantages and pitfalls. My collection included speeches from eighty-one campaigns (thirty-eight Republican, forty-three Democratic) and seventy-two individual candidates (all of the presidents who served a first term ran for another, and some of the also-rans failed in multiple tries). The total corpus ran to nearly seven million words, far more than any one person might care to read—even a political junkie, which I’m not—and so I dumped all the speeches into a database. Nonetheless, the analysis below should be considered suggestive rather than definitive. Those millions of words and thousands of speeches come from only a fewscore politicians and their speechwriters. By necessity, a large proportion of the speeches come from a pair of men: George W. Bush and Barack Obama, their parties’ nominees in two elections, loom large (although, as it turns out, Bush and his team did not refer that much to the American Revolution). Other candidates, like Rick Santorum and Bill Clinton, stand out because they often brought up the founding generation. So we must take into account the context and tone of these references, as well as realize that we are dealing with the idiosyncrasies of men and women with large egos, some of whom lead lives with few checks on their loquaciousness (Exhibit A: Newt Gingrich; Exhibit B: Joe Biden).

I searched the entire corpus for a variety of terms, names, dates, and phrases that relate to the American Revolution. Some of these were obvious, including people such as Washington, Jefferson, Thomas Paine, and John Adams; documents like the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights; dates like 1776 and 1789; and phrases like “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” and “we the people.” I also combed for terms that refer to the Revolutionary generation, like “founders,” “framers,” and “patriots.” In addition, I looked for people and phrases not usually included among the founders but still from that era, like Crispus Attucks (a person of color who was shot in the Boston Massacre), as well as some that scholars would be more likely to be familiar with than the general public, such as George Robert Twelves Hewes and Deborah Sampson. Not surprisingly, none of these more obscure people showed up in candidates’ speeches. Intriguingly, Benjamin Franklin did not show up in many election cycles either, despite boasting what current pollsters would call the highest “name recognition” of any of that generation who didn’t become president. I then read through the paragraph containing each occurrence to determine whether it was indeed a reference to the American Revolution. Some terms required some judgment as to what to include and what to exclude. For example, the “Constitution” could refer to the founding document or to the nation’s current governing structure. “Washington” could signify the man, the state, or the federal capital (there were over 4,400 hits for “Washington,” fewer than a couple hundred of which were really about Martha’s husband, and fewer than a handful about Martha herself). When in doubt, I opted for inclusiveness, knowing that such terms can work on multiple levels rhetorically and in audiences’ mental associations with them. The data provide a broad and detailed picture of the ways that candidates invoked aspects of the American Revolution.

Not surprisingly, my survey of these speeches revealed a surfeit of references to the American Revolution. The oft-repeated dictum that the United States is more an idea than an ethnic or cultural construct (as opposed to, say, Italy or Russia or Germany) is overblown: try explaining to nearly anyone else in the world the attraction of peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches or tractor pulls. Nonetheless, the Revolution serves multiple purposes in the national political consciousness. The American Revolution resulted in the creation of the United States as a nation-state, and it continues under the federal political structure devised by the founding generation. The ideals of liberty and equality, the idea of limited government, and the fundamental notion of a polity of laws stem from the founding period and form a significant portion of national identity. The Revolutionary period serves as the font of many of our politically useful national myths, complete with its pantheon of heroes and villains, causes and stories, and even, in the form of slavery, what so many have called an “original sin.” For civic entreaties, it offers personae with idealized characteristics: Washington, the personification of fearless leadership; Jefferson, the eloquent avatar of democratic idealism and small government; Adams, the persistent champion of liberty; and Franklin, patron saint of upward mobility and civic participation. Because these men and their colleagues composed the documents that continue to be at the center of the American governance, especially the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, they can be cited as the ultimate appeal to authority on current policy disputes that involve questions of constitutionality. Furthermore, like the minuteman, the ordinary citizen ready to drop everything to serve his country at a moment’s notice, they provide examples of civic virtue. And despite belying the political and social structures put in place in the late eighteenth century, the American Revolution’s lofty egalitarian rhetoric provides uplifting elocutions from the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution to Paine’s Common Sense and The American Crisis. The Revolution continues its role as a touchstone in American political culture.

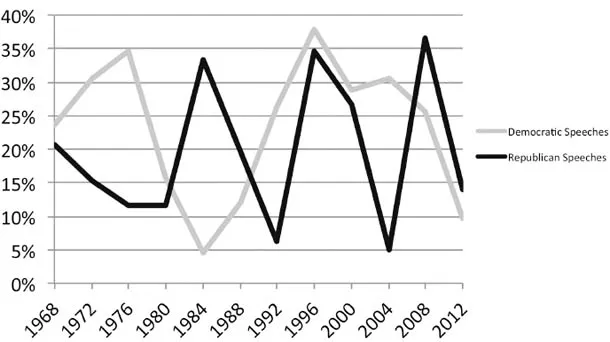

Figure 1.1. Percentage of Speeches in Which “American Revolution” Was Mentioned, by Presidential Election Cycle

There has been no constant quantitative pattern over time to explain how often presidential hopefuls refer to the Revolutionary era. Sometimes many primary candidates from a particular party brought it up, sometimes not. Incumbency seemed to make no difference, nor did the party affiliation of the incumbent or challenger. In 1996, Bill Clinton appeared particularly fond of Revolutionary references. And yet, though he sprinkled the Revolution in a greater proportion of his speeches in that election cycle than in 1992, he actually addressed it more intensively within the few speeches in which he mentioned it during his first presidential campaign. George W. Bush, however, invoked the Revolution less often and in fewer speeches during his 2004 reelection campaign than in his first bid for the presidency in 2000. Interestingly, in elections with no incumbent, candidates from the two parties invoked the Revolution at fairly similar rates. There appears to be no significant spike during the 1976 Bicentennial of Independence or near the two hundredth anniversary of the ratification of the Constitution in 1989. If any pattern presents itself at all, it is that candidates in the party out of power generally mention the Revolution more than candidates of the party in power, but not all the time, and not always by much. In short, the overall numbers don’t necessarily tell a clear story here.

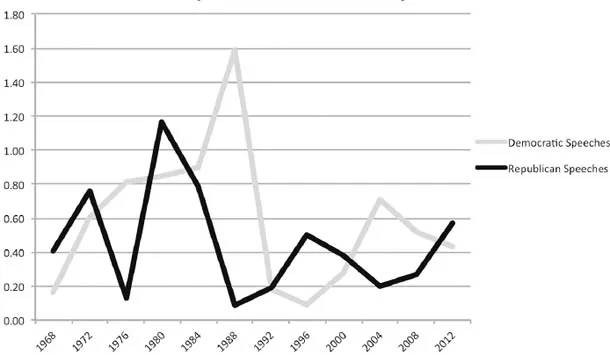

Figure 1.2. Number of “American Revolution” Mentions per Speech, by Presidential Election Cycle

A more complete picture comes from looking at individual references, how they were used, and in what context. During the 2008 presidential election cycle, candidates of both parties invoked the American Revolutionary era in nearly one-third of their speeches, Democrats in a quarter of their speeches, and Republicans in over a third of theirs. They tended to do so in several modes. Most obviously, speakers cited the nation’s founding generation in an appeal to authority. This could be done collectively, as when Joe Biden noted that “the Framers . . . included habeas corpus in the body of the Constitution itself” in his critique of the Bush Administration’s detention policies in the war on terror. They also mouthed the well-turned phrases of particular founding fathers. Rudy Giuliani advocated a strong military by reminding voters that “George Washington told us more than 220 years ago . . . ‘There is nothing so likely to produce peace as to be well-prepared to meet an enemy.’” Quoting the founders represents a strong rhetorical gambit, reflecting the assumption that no one can gainsay Jefferson on the meaning of the Declaration of Independence or the members of the Constitutional Convention on the meaning of the Constitution.

Candidates brought up those founding documents explicitly. Sometimes they did so to establish their dedication to lasting American ideals. Fred Thompson told one audience he did not “think the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution are outmoded documents,” signaling that he was in favor of traditional approaches to current issues. At other times, speakers invoked these charters because, in title and in content, they resonate so deeply in the American consciousness, as John McCain did when he promised “a national energy strategy that will amount to a declaration of independence from the risk bred by our reliance on petro-dictators.” And occasionally they cited the Revolution to parade their patriotism. In a speech at Independence, Missouri, the week before Independence Day, Barack Obama invoked the Battles of Lexington and Concord, when, with “a shot heard ’round the world the American Revolution, and America’s experiment with democracy, began.” For a politician, talking up the Revolution represents a low-risk speech-writing strategy.

How candidates spoke about the Revolution represented both a historical interpretation and a philosophy of history itself. Republicans generally espoused what I will call here an “essentialist” view of the Revolution. For them, there is a definitive past, a real past, an unchanging past we can study for guidance, wisdom, and understanding. If we as contemporary Americans want to understand the political structures we inhabit, structures that have lasted in their current form longer than any other contemporary democratic republic, then we had best look at the men who drafted the blueprints. The founders knew well enough to draw up a brilliant and durable design and successfully craft the building and, so, can be authorities worth consulting not only on what they built but also on how it can weather new storms. Interpretations concerning people other than the men who wrote the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution are not necessarily wrong, but they are beside the point, just as a newspaper story about people watching a building go up may be nice in telling us about them but would not change what that building looks like, how it functions, or whom we might ask to know about it. And if the building seems not always to function as it should, we might need to redo the wiring or fix the plumbing, but otherwise we should keep the floor plan that has served us so well, work to spiff it up, and restore it to its former glory. When 2008 Republican hopeful Mike Huckabee spoke about the signers of the Declaration of Independence, he paraphrased its last line in imploring his listeners to “pledge our lives, our families, our fortunes, and our sacred honor to that which is true, which is right, and which is eternal.” According to this viewpoint, the United States has survived through its fidelity to immutable doctrines central to the American Revolution that continue to be at its essence: national self-determination, the sanctity of private property, suspicion of central government, and a particular form of Christian values.

Essentialism is also a reaction to what most conservatives rightly perceive as the multicultural challenge to their basis of power, especially given the increasing reality of self-identified conservatives who are p...