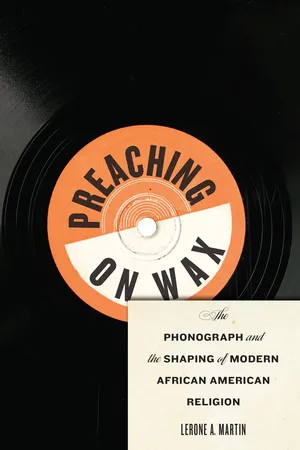

![]()

1

“The Machine Which Talks!”

The Phonograph in American Life and Culture

Thomas Edison was awestruck. Following the first successful test of the talking machine in November 1877, the inventor recalled, “I was never so taken aback in my life!” He was not alone in his astonishment. The Scientific American, a popular science magazine (published continuously since 1845), was also flabbergasted. In December 1877, Edison presented his novelty to more than a dozen scientists and admirers gathered in the journal’s New York offices. Edison turned the crank of the phonograph and the prerecorded tinfoil cylinder squeaked out, “How do you like the phonograph?” The small assembly looked on in disbelief. “No matter how familiar a person may be with modern machinery and its wonderful performances,” the publication proclaimed, “it is impossible to listen to the mechanical speech without his experiencing the idea that his senses are deceiving him.” It was not a deception. The phonograph recorded and reproduced sound across the chasms of mortality, time, and distance.1

The experience was so jolting, Edison questioned if the world was ready. In past times, he told a reporter, the public would have probably “destroy[ed] the machine as an invention of the devil and mob[bed] the agents as his regular imps.” Perhaps now, Edison hoped, the modern world was ready to accept a talking apparatus. The 1878 gathering of the National Academy of Sciences in Washington D.C., revealed that society was initially divided on the issue. Several observers fainted when he presented “the Talking Machine.” One observer was overcome with an eerie feeling of evil as the phonograph repeated Edison’s words, shouts, and whistles. The unnerved eyewitness remarked that the phonograph “sounds more like the devil every time.” The academy’s council, however, praised Edison above all others, declaring, “These other men are only inventors—You, sir, are a discoverer!” Following the astonishing presentation, Edison went to the White House and gave President Hayes and his wife a private demonstration. The showing turned into a celebration, lasting until the wee hours of the morning.2

Unlike the enthusiastic witnesses at the White House, some cultured observers, such as noted scholar Georges Duhamel, were stunned into skepticism. The accomplished intellectual, born in 1884, witnessed the rise of the phonograph with great distrust. Duhamel, in his In Defense of Letters, warned that the communicative abilities of the phonograph (as well as radio) would destroy the foundation of Western culture, particularly reading and book publishing.3 Similarly, a Yale professor expressed distrusts of the phonograph, telling one journalist that the very existence of a “talking machine is ridiculous!”4 Detractors believed that a device that preserved and relayed sound was ghostly and culturally detrimental at worst, absurd and useless at best.

The trepidation was understandable. The talking machine revolutionized the aural world. The “sound writer” allowed listeners the unprecedented opportunity to hear almost any variety of sound they wanted time and again. In the first press release for the phonograph, Edison stated that the machine was the first “apparatus for recording automatically the human voice and reproducing the same at any future period … immediately or years afterward.”5 Furthermore, he explained to an awestruck Washington Post reporter, “This tongue-less, toothless instrument without a larynx or pharynx, dumb, voiceless matter, nevertheless mimics your tones, speaks with your voice, utters your words, and centuries after you have crumbled into dust will repeat again and again, to a generation that could never know you.” Edison’s explanation led the reporter to ponder if the device came from heaven. “If every idle thought and every vain word which man thinks or utters are recorded in the judgment book,” the reporter wondered, “does the recording angel sit beside a celestial phonograph, against whose spiritual diaphragm some mysterious ether presses the record of a human life?”6 For many, only transcendence could explain the incomparable machine.

Religiously inclined or not, the public was fixated by the phonograph. The Chicago Daily Tribune noted that no other invention had “created such an interest and attracted such widespread attention as the Phonograph.”7 In 1902, the U.S. Census Bureau concluded, “Of the many wonderful inventions during the past quarter century perhaps none has aroused more general and widespread interest among all classes of people than the machine which talks; and for this reason, together with the fact that it has been widely exhibited, nearly everyone is more or less familiar with the so-called talking machine.”8 Americans were taken by the sound writer.

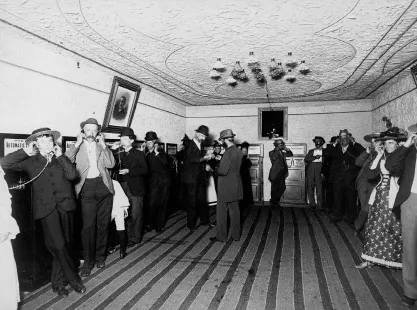

Figure 1.1: Listeners enjoying the talking machine through the customary small rubber tubes at a public venue. Source: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Thomas Edison National Historical Park.

The phonograph became the primary entertainment medium in American life and a cornerstone of modern domestic life. Beginning in the early twentieth century, wealthy residences and impoverished domiciles alike possessed at least one talking machine. In our contemporary moment, the primary entertainment mediums are televisions, computers, and smart phones. In the first few decades of the twentieth century it was the phonograph. Before radio was broadly adopted in American homes, the talking machine brought all aspects of American life into the home. Emile Berliner, the inventor of flat disc records—easier to use and store than Edison’s cumbersome tinfoil cylinders—foresaw the centrality of the phonograph. Shortly after unveiling his wax disc in 1888, the German immigrant told a gathering of Philadelphia’s Franklin Institute for Science Education that the uniform ease with which his new discovery could record, reproduce, and copy sound would give way to a new form of popular entertainment. “Whole evenings,” he predicted, “will be spent at home going through a long list of interesting performances … of prominent singers, speakers, and performers.”9 Berliner was clairvoyant. Americans would indeed gather at home and various other spaces to enjoy music, current events, landmark speeches, political debates, and religion—all through their phonographs.

The Phonograph in American Consumer Culture

The phonograph began as a commercial amusement device in train stations, taverns, hotels, small businesses, and various exhibitions. By 1890, the city of Atlanta, for example, had a total of nine commercial machines. For a nickel, consumers could behold the marvel of hearing the round wax cylinders squeak out a musical rendition through a pair of small rubber tubes (Figure 1.1). Despite the fee, such commercial use proved popular and lucrative. Edison representatives traveled to Atlanta and were pleased to learn that their “Nickel in the Slot” phonographs were receiving a “great deal” of use in the city. One Atlanta newspaper observed that the device had “won a place in the affections of our people from which it can never be dislodged.” One city saloon phonograph reaped over $1,000 in just four months. The phonograph was the emerging avenue of commercial entertainment.10

The phonograph industry grew at an exceedingly fast pace. In 1897, the nation purchased about half a million records. Two years later, about 2.8 million records were consumed annually, and the number kept rising. Before World War I, there were eighteen established phonograph companies. Collectively, they sold 500,000 phonographs. Near the end of World War I, the number of phonograph manufactures had risen from eighteen to two hundred and their combined phonograph production climbed from a half million to 2.2 million.11

Three companies—Edison, Columbia, and Victor (RCA-Victor beginning in 1929)—dominated the widespread growth of the phonograph. Within a decade of the invention, Edison’s phonograph division employed 600 men. By the turn of the century, sales of Edison’s phonograph products exceeded $1 million, a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) that amounts to a contemporary equivalent of $734 million. At the company’s peak, worldwide phonograph sales topped 140,000 and record sales were just short of 8 million. Columbia, founded in 1888, brought innovation to the industry and eventually surpassed Edison. The company, which introduced the nation to double-sided records in 1908, amassed assets of $19 million ($4.8 billion today) near the end of World War I. The Victor Talking Machine Company, however, was the most lucrative. Founded in 1901, the company grew at a shocking pace. In its initial year, the company sold 7,570 phonographs. For its tenth anniversary in 1911, annual sales had increased 1,600 percent to 124,000 phonographs. Toward the end of World War I, the company was housed in a 1.2 million square foot facility and endowed with assets of $33 million, a contemporary equivalent of $6.57 billion. By 1921, the wealthy company was selling approximately 55 million records a year and enjoying a higher advertising expenditure than prominent companies such as Colgate, Goodyear, and Kodak. In all, Victor’s advertising costs ranked second among all U.S. businesses, trailing only its celebrated Camden, New Jersey neighbor: Campbell’s Soup.12 The Victor advertising logo, entitled “His Master’s Voice” (an image of a white dog listening intently and curiously to a phonograph), was seemingly ubiquitous in American life. Today, the image and slogan remain a cultural icon.13

The three titans of the phonograph industry were the bastions of big business. During the industry’s height, Americans were annually spending $250 million ($51.4 billion today) on products bearing the names of Edison, Columbia, and Victor. At their pinnacle, the companies collectively had annual profits in the range of $125 million ($25.7 billion today).14 The phonograph industry was a staple in American consumer culture—a sphere that helped to shape the experiences, tastes, habits, and cultural practices of the early twentieth century and beyond.

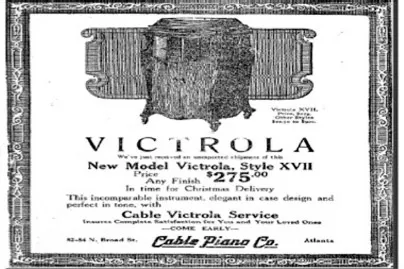

Figure 1.2: 1918 phonograph advertisement showing prices ranging from $22.50 to $900. Source: Atlanta Constitution, December 24, 1918, 7.

The Ubiquity of the Phonograph in American Daily Life

The Victrola solidified the phonograph’s place in American homes. The Victor Talking Machine Company introduced the device in 1906. The home entertainment center was comprised of enclosed parts and hidden speakers (a sound horn) in an oak or mahogany casing. In addition, the cabinet provided shelf space for storing a music library, making it simultaneously a sound medium and an exclusive piece of home décor. The Talking Machine World, the premiere journal for the phonograph industry, declared at the close of World War I, “The phonograph is about to enter a period of unparalleled popularity as a national household article.”15

The innovation was extremely popular. President Woodrow Wilson took his enclosed phonograph with him for his journey to the Paris Peace Conference following the close of World War I. The president boarded the George Washington ocean liner for his trip across the Atlantic Ocean equipped with his stylish phonograph and library of one hundred records. Few things could make the long journey feel more like home than the domestic entertainment medium.16 The nation followed suit. A 1925 study of thirty-six small U.S. cities concluded that more than half (59 percent) of homes had a phonograph. The device was equally popular in large cities. A 1927 study of home equipment in cities of 100,000 or more found that 60 percent of homes owned a phonograph, compared to 23 percent who owned a radio.17 The phonograph, once a novelty, had become a centerpiece of the American home.

In 1921, Mrs. Mary Kelly, a mother of five, wrote to the Edison phonograph company saying as much. “I have had my life made worth living since it [the phonograph] came into my home.” The Providence, Rhode Island, resident praised her inexpensive phonograph for improving her quality of life. Mrs. Kelly was attached to her phonograph. She disclosed that she planned to save money not for a radio but for an expensive mahogany cabinet phonograph, declaring, “There is no case too grand for such a glorious machine!”18

The industry attempted to meet all aesthetic and economic tastes. Phonographs were soon available in an assortment of models, including designs in the likeness of small grand pianos, overnight bags, suitcases, leather purses, handbags, and eventually small players that could be concealed behind walls and ceiling tiles. Such designs varied in price. In 1918, one leading company advertised its arsenal of phonographs in the price range of $22 to $900 (Figure 1.2). The price range is significant compared to the average annual family income, which was approximately $1,500 at the time.19 Nevertheless, some consumers thoroughly enjoyed the elite priced phonographs. In 1921, George Rhulen of Tacoma, Washington, wrote to the Edison Company to express the joy he derived from his $285 Edison phonograph (the equivalent of approximately $3,700 today).20

The phonograph became a seminal commodity of conspicuous consumption in the modern home. Garvin Bushell, a member of the first band to record a race record, recalled that the kind of phonograph one purchased was a symbol of one’s social and economic significance. His family purchased their first Victrola for Christmas in 1917. Bushell mar...