![]()

[1]

HARDY PURITAN PIONEERS

The story of Elizabeth Tuttle’s unhappy marriage has several possible beginnings. This telling starts with the Planter, which in April 1635 was moored in the Port of London awaiting its second voyage to the Massachusetts Bay colony.1 England in the seventeenth century had a flourishing river life, and the River Thames was constantly congested with traffic. The Planter was but one of a bewildering variety of watercraft—pinnaces, ketches, lighters, wherries, barks, shallops, pinks, and sloops, to cite just a few—that sailed its waters at any one time. Although boats were free to moor as they liked, large merchant vessels generally dropped anchor in the pool below London Bridge and discharged their cargo at Billingsgate and the other legal quays, for the bridge’s narrow arches and rapid waters made passage treacherous even with the drawbridge raised.2 Skilled watermen piloted barges and other small craft upriver to unload their goods at Queenhithe and the many wharves and landing places that crowded the north bank of the river. And along the waterfront from Westminster to the Tower, boats also picked up and discharged passengers who found water travel more convenient than navigating the dirty cobblestone streets of the capital city.3

The ship that transported Elizabeth’s family to the New World had been built the previous year in Wapping, through the investment of two puritan merchants and its master, Nicholas Trerise. At 170 tons, the Planter was a medium-sized vessel, likely having two decks in its main hull to accommodate the crew, cargo, and provisions necessary for the long voyage. In March 1634, just prior to the ship’s first sailing to Massachusetts Bay, its owners had obtained a certificate permitting them “to furnish their ship with ordnance out of the founder’s store,” for like other sea-going ships, the Planter could not venture from port without the arms to protect itself from privateers.4 The following spring it was boarding passengers for a second trip to New England, as one of five ships that sailed from London to Boston in April 1635 at the height of the puritan migration.5

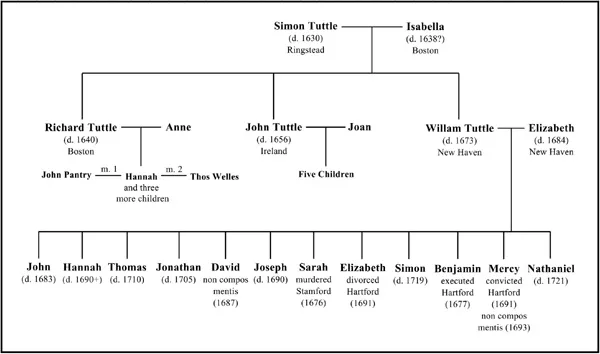

Tuttle genealogy. Illustrated by John Luchin.

The Planter transported 118 English colonists on this second voyage, considerably more than the average of 69 passengers that sailed on New England-bound ships in 1635. The “closeness” of the ship would have been mitigated, however, by the near-relation of many on board. The composition of its passengers clearly illustrates that “travelers organized themselves so as to brave the uncertainty of an Atlantic crossing with relatives and neighbors.” The historian Allison Games estimates that at least 35 of the passengers traveled from St. Albans, Hertfordshire, to board the Planter together, and approximately 40 percent of the ship’s passengers whose county of origin can be identified were residents of Hertfordshire. Another roughly 22 percent came from the county of Suffolk, with smaller percentages from Northamptonshire and Middlesex.6 And within these geographical groupings most passengers traveled in the company of family members. The New England migration comprised primarily families. Although estimates vary, the number of family cohorts was high, ranging between 60 and 90 percent depending on the sample.7 Commonly a married couple and their children made the voyage together, but a significant number of “extended families of sometimes extraordinary complexity” relocated to New England as one company.8

The Tuttle clan was certainly the largest family company on the Planter and one of the largest extended families to emigrate as a group in 1635. Three Tuttle brothers were the group’s core household heads. Richard Tuttle, who at forty-two was the eldest, sailed with his wife, Anne, and their three children, ranging in age from six to twelve years. John Tuttle and his wife, Joan, ages thirty-nine and forty-two respectively, traveled not only with their four young children but also with four older children from Joan’s previous marriage and her eldest daughter’s new husband. William Tuttle, the youngest brother, was twenty-six years old when he boarded the Planter. He and his wife, Elizabeth—future parents of the Elizabeth Tuttle who is our story’s protagonist—brought with them three children less than four years of age, including a three-month-old infant. In addition to this horizontal sibling network, the company of Tuttles also extended vertically to include Isabella Tuttle, the brothers’ seventy-year-old mother, and John Tuttle’s sixty-five-year-old mother-in-law.9 Counting servants, who were considered part of their masters’ households, the large company traveling with the Tuttles to Massachusetts Bay reached a total of twenty-seven members, and possibly more.10

Debate about the motivations for migration has focused on the economic and religious factors that pushed and pulled so many English men and women to leave their homeland between 1620 and 1640. Most historians, however, agree that “[m]onocausal explanations of motivation are simplistic and unhistorical,” arguing instead that “a number of factors intersected to form a matrix of migration.”11 To more effectively map this matrix, recent work on the migration has focused on an analysis of the regional and local conditions of life in early Stuart England, where such data is available.12 But if the migration “had as much to do with private hopes and frustrations, and opportunities of the moment, as with assessments of the comparative religious and economic prospects of England and America,” then individual explanations will ultimately remain opaque to us.13 Because the emigrants left few traces of their decision-making processes, “historians of the Great Migration must live in a world of the plausible, not the conclusive.”14

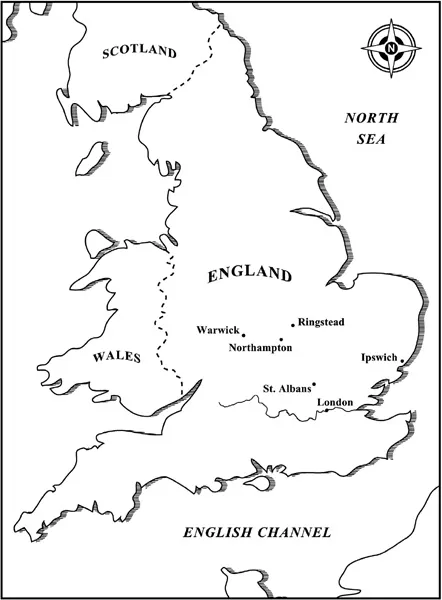

The “plausible” story of the Tuttles’ migration begins in the English Midlands. They were a Northamptonshire family that hailed from the village of Ringstead, located in the northeastern part of the county about twenty miles from the county town of Northampton. By 1635, the year of their migration, John had moved to Hertfordshire to pursue a career in the cloth trade, while Richard and William were raising families of their own in Ringstead. These three brothers, and their wives and children, must have spent long hours debating the merits of migration. What did not lead them out of England is, however, easier to identify than what did. The Tuttles may have been pushed by financial worries or pulled by hopes for greater gain, but like most migrants they did not flee England to escape poverty or financial ruin.15

The Tuttles were a family of middling status, neither gentry nor landless poor but prosperous landowners who made a living farming and raising sheep. The brothers’ father described himself as a “yeoman.”16 One step on the rural social ladder below the gentry, yeomen traditionally held land in freehold having an annual value of 40 shillings or more. In practice, however, yeomen were substantial farmers who earned incomes that could range anywhere from £40 to £200 a year, trading surplus agricultural products on the growing English commodities market.17 That the Tuttle patriarch was a freeholder is confirmed by a 1605 list that named him one of seven men of this status in the village of Ringstead.18 Given that this village had no resident gentry, Simon Tuttle and his fellow yeomen would have occupied a position at the top of the local hierarchy, the “cocks of their parish.”19

The Midlands was England’s principal grain-producing region. Its yeomen typically raised crops of wheat, barley, and peas and supplemented their income through other rural pursuits, such as cattle and sheep grazing, in a practice known as mixed husbandry.20 The Tuttles, for example, owned a malt mill, which suggests that they, like many Midlands families, grew barley and brewed their own ale, and they raised sheep to take advantage of the expanding market for wool, which had by the early seventeenth century become one of Northamptonshire’s main cash crops.21 These commodities would have cushioned the Tuttles against the volatile market that troubled early modern England, allowing the family to withstand times of dearth and profit from shortages and rising prices. Like other well-positioned yeomen, Simon Tuttle used his profits to expand his land holdings.22 While small farmers floundered in the marketplace and lost their land to enclosure, his family’s standard of living improved.

England, 1600s. Illustrated by John Luchin.

Despite this economic success, the Tuttles were undoubtedly affected by the general social upheaval that accompanied the enclosure of common farmland in their region. By the end of the fifteenth century almost half the arable land in England had been fenced.23 The Midlands in general and Northamptonshire in particular were hit hard by the adoption of this new method of land management, which ended the customary right of peasants and small landowners to farm open fields. According to the enclosure commissions of 1517 and 1607, the total acres enclosed was far higher in this county than in others investigated.24 In response, Rocking-ham Forest, which occupied much of the region north of Ringstead, experienced a surge in population as displaced small farmers and unemployed rural wage earners were attracted to its ample common lands and forest industries.25 The incidence of enclosure riots also increased in the area, climaxing in the Midland Revolt of 1607, the largest of the riots during James I’s reign. Violence began in several villages just west of Ringstead, near the market town of Kettering, before spreading to the neighboring counties of Warwick and Leicester.26 Desperate agricultural workers, according to one contemporary observer, “violently cut and broke down hedges, filled up ditches, and laid open all such inclosures of commons and grounds as they found enclosed.” The rioting continued for several weeks, until the ringleaders were hanged and their quarters publicly displayed in various Northamptonshire towns, including Thrapston, located only a few miles north of Ringstead.27

Although these changes were often disastrous for small farmers, yeomen, whose interests largely coincided with those of large gentlemen landowners, recognized their advantages and actively implemented enclosure on their lands. The Tuttles likely profited from such uncertain economic times, but they were also surely aware of the risks. The volatility of the agricultural market may have encouraged the second son to abandon rural life and pursue a career in the cloth trade. Internal migration was commonplace in early-seventeenth-century England, “a part of the life cycle for most young men and women.”28 Many moved to escape poverty and starvation, others for economic betterment. Such betterment migrants were commonly children of rural landowners who had the resources to start a son in an urban trade. Because wealthy townsmen occupied a social status higher than that of rural yeomanry, such a move could be a step up.29

The Tuttles established their son in St. Albans, located about fifty miles southeast of Ringstead in Hertfordshire. Travelers from nearby London regularly lodged in the many inns that lined this ancient abbey town’s central thoroughfare, as did farmers and merchants coming from East Anglia to trade at its twice-weekly market.30 In this likely location John Tuttle set up business, paying £6 “freedom money” to gain admission into the Mercers’ Guild, one of the four companies that dominated the town’s local economy.31 Mercers, who traditionally dealt in such luxury fabrics as silk, linen, and fustian, faced during this period increased competition from unlicensed tradesmen and suffered from the depression that crippled the cloth trade in the early seventeenth century, as it shifted from dealing in broadcloth to “New Draperies.”32 Despite such challenging economic times, John appears to have flourished in St. Albans; he married a wealthy widow with an £800 estate and joined the town elite.33

The Tuttle brothers also benefited from their father’s skillful financial management. When he died in 1630, Simon Tuttle left all three of his sons with sufficient means to be independent householders. The eldest, who had already obtained his portion of the estate, received only a modest inheritance, consisting of a few acres of pastureland and “half a dusson sheepe.”34 The second son was given “a dwelling house” in Ringstead, “with all the houses thereunto belonginge and the yard and orchard thereunto adjoyning.” William, the son of principal interest to this story, was unmarried when his father died and, unlike his older brothers, had not yet been set up in a career. He accordingly was granted the bulk of the estate, but his father ensured a comfortable maintenance for his widow by stipulating that his youngest son would inherit only after his mother’s death. Isabella’s life estate included the “house, messuage, or tenement wherein I now dwell, togither with all the houses, landes, yardes, meadowes, pastures, commons, profits, commodities, and appurten...