![]()

1

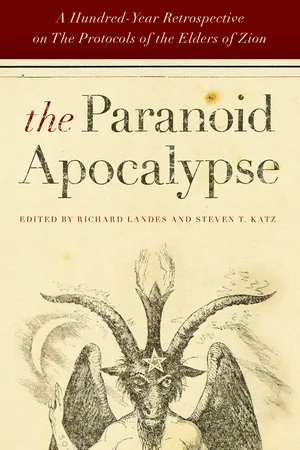

Introduction

The Protocols at the Dawn of the 21st Century

RICHARD LANDES AND STEVEN T. KATZ

This volume of essays results from a conference held at the Elie Weisel Center for Jewish Studies at Boston University with the collaboration of the Center for Millennial Studies at Boston University a century after the publication of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

The Protocols stands out as both one of the most malicious forgeries in history—“an atrocity-producing narrative”—and the most widely distributed forgery in the world. Soon after publication, believers translated its “revelations” about an international Jewish conspiracy to enslave mankind into dozens of languages and spread the text from its Russian foyer to the rest of Europe, the Americas, and as far as Japan. At the height of its first wave of influence (1905–1945), it played a key role in inspiring and justifying the Nazi attempt at genocide of the Jews.

After the catastrophe wrought by a great and powerful nation seized by a genocidal paranoia in response to the conspiracy it perceived via the Protocols, those who vanquished it renounced and denounced the mad text. Modernity had won, and the broad public consensus held that “Nie Wieder” [Never Again] would we see either the “bloody tide” or the forged fantasies that fueled it. The Protocols quickly became a taboo subject in the West. Anyone who referred to it incurred the stigma of both ignorance and hate-mongering. Civil society, with its egalitarian rules, its scientific skepticism, and its high levels of tolerance for the “other,” had won the battle against xenophobic paranoia. New, unthinkable institutions of international cooperation—the United Nations, the European Union—arose and survived in this new dispensation.

One might call this postwar attitude, embodied in Norman Cohn’s path-breaking and disturbing study, Warrant for Genocide, the “modern” solution to the Protocols. “Positivist historiography,” dedicated to find out “what really happened” (however the scientific chips about objective reality fall), condemned the Protocols, just as it condemned the forged evidence in the Dreyfus Affair. After the Nazis, the same “positivist” trials that, in 1923, had failed to quell belief in the Protocols, became normative. Sadder but wiser, the post-Holocaust world adopted the “modernist” position—the Protocols are a malevolent forgery, an “atrociously written piece of reactionary balderdash.”1 And, hand in hand with that conclusion, modernists held that anti-Semitism is a historically proven social and political toxin banished from legitimate discussion by political correctness.

This itself is part of a much broader consensus on the nature of the public sphere and what constitutes sane discourse in the period after the Holocaust. Human rights, respect for other people and cultures, self-criticism, historical accuracy all participate in a mild international experiment in transformative millennialism: the universal inauguration of civil society. People—Jews and Gentiles—who express astonishment at the return to prominence of the Protocols in our day represent the intellectual products of just such a paradigmatic approach to the public discussion in which the Protocols was understandably and justifiably banned.2

When Richard Landes first read the Protocols, while teaching at Columbia in 1985, he was part of this modern consensus. He was surprised by what he read. It turned out he had been hearing echoes of this text—what Stephen Bronner calls “analogs”—all the time, in particular from radicals at Berkeley, where he had spent the previous years arguing with them on Sproul Plaza about the Israelis in Lebanon. “The Jews control the media … the Jews control the markets [including the oil markets] … the Israelis are doing to the Palestinians what the Nazis did to them … Israel is part of a conspiracy with America to rule the world.” An Iranian group even handed out a flier with excerpts from the Protocols. When he realized that the teachings of the Protocols were filtering back into political discourse, he suggested a scholarly edition, one that allowed informed citizens to become aware of the sources of such paranoid and demonizing rhetoric.

Then came his second surprise: Virtually everyone disagreed with him. As Fritz Stern, the senior professor in German history in the department, put it pithily, “You think you’re inoculating people, but you’re spreading the disease.” That was 1985, when the Protocols seemed a dead letter to most, and keeping it quiet seemed like a good idea. They were halcyon days when Sartrian analysts figured that, with anti-Semitism nearly vanished from America, the Jews would soon follow.3

That was before the Internet, before Amazon.com, before everyone had access to the Protocols, not just from Iranian students’ fliers at UCB or Louis Farrakhan’s bookstores but also from Walmart. That was before cable television and growing sophistication in movie-making in the Arab world produced serial programs bringing the Protocols to television screens around the world. And that was before, beginning in October 2000, the “New Anti-Semitism” in word and deed entered its global phase, allowing the virus that Fritz Stern had spoken of to spread far and wide, and before 9/11 triggered a wave of conspiracy theories that revived the Protocols in America, as Marc Levin suggests in his film, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.4 Its currency today—both as a text and as an analog, as a conspiratorial idea—in so many circles, right and left, high and low, red state, blue state, has to alarm anyone who keeps track of such things and understands the stakes. How can we understand this disturbing revival?

The chapters in this volume attempt to provide the reader with a range of information and analytic tools to understand four major questions:

1. What are the cultural origins of the Protocols?

2. What explains the Protocols’ continued appeal?

3. Under what conditions does belief in the Protocols get activated and produce atrocities?

4. What, if anything, can be done to oppose the spread of belief in so dishonest and disastrous a libel?

Three major themes emerged from the conference in terms of the power exercised by the Protocols—(1) the psychological nature of paranoia in its appeal, (2) the problem of “truth” and the exegetical shiftiness that detaches the text from its empirical moorings as a forgery, and (3) the power of apocalyptic belief in “activating” the text as a social and political player. We present first two conceptual essays as introduction, then essays, primarily in historical order of topic.

Apocalyptic Conspiracy, Moral Failure, and the Crises of Modernity

We open this volume with two chapters that address this broader context on the one hand from the perspective of the historical longue durée, and on the other from a psychological one.

The first chapter (by Richard Landes) explores the way in which the Protocols takes up a very long and largely dominant strain of political thought, articulated by the ancient Athenians as “the law that those who can, do what they will, and those who cannot, suffer what they must.” This represents the Machiavellian position in fact rejected by the very text the Protocols plagiarized, the Dialogue in Hell between Machiavelli and Montesquieu. Eli Sagan, in a remarkable book on the origins and dangers of democracy, called this position the “paranoid imperative”: Rule or be ruled.

This approach systematically projects the lust to dominate onto others, thereby justifying preemptive aggression: Do onto others before they do onto you. To understand both the logic and the appeal of the Protocols, one has to appreciate how profoundly consistent that projection is, how much it has shaped political relations both between elites and commoners and between states for millennia, during which “democracy” was a dirty word. Both Thrasymachus and Plato—“might makes right” and “justice is harmony”—at least agreed that democracy was a recipe for chaos and tyranny.

When one factors in the anxieties of freedom so lucidly analyzed by Erich Fromm more than a half-century ago,5 one can understand how a modernity built on egalitarian slogans and democratic freedoms represents a terrifying anomaly to this “political philosophy” of longue durée. For people steeped in this tradition, taking away their right to dominate must be part of a larger plan to destroy them; democracy must be a prelude to slavery. No one can actually push democracy and its correlates—free press, legal equality of commoner and aristocrats, free markets—honestly. There must be a hidden agenda, and that agenda must be domination.

The Jew, in the Protocols, is, thus, necessarily a demopath—someone who uses and manipulates democratic values as a way to trap people for a despotic agenda, using the promise of democracy to enslave people. Only a dupe and a fool could sincerely support human freedom. The forgers of the text reason that the Jews can be neither. Behind every crusader for freedom and equality, warns the Protocols, lies a tyrant in waiting. And since both the French and the Russian revolutions rapidly turned from their egalitarian promises to dictatorial terror, the Protocols struck many an observer in the 1920s as prophetic. The Protocols was the demopath’s Bible, and its publication ripped off modernity’s beneficent mask to reveal its “true” malevolent agenda.

The more widespread modernity became, the more threatening the process appeared. And the more modernity has spread, the more globalization now penetrates into cultures the world over, the more hostility it provokes. By the early 20th century, a struggle of cosmic proportions emerged, most visibly among the humiliated and defeated Germans: This was an apocalyptic war in which “paranoid imperative” shifted from “rule or be ruled” to exterminate or be exterminated.6

Strozier’s chapter explores from a psychological perspective “the links between paranoia and the apocalyptic and how and why that relates to violence.” Rooted in a therapeutic practice that involved close contact with paranoids, he offers observations that take us inside the experience of people in the grip of such compelling beliefs.

The paranoid lives in a world of heated exaggerations, one in which empathy has been leached out and one that lacks as well humor, creativity, and wisdom. The paranoid lives in a world of shame and humiliation, of suspiciousness, aggressivity, and dualisms that separate out all good from pure evil … grandiose and megalomaniacal and always has an apocalyptic view of history that contains within it a mythical sense of time. Many paranoids are very smart … paranoia focuses all of one’s cognitive abilities in ways that can make one’s schemes intellectually daunting—which is why I have always thought that paranoia is a pathology of choice for the gifted.

Apocalyptic intensity creates a self-enforcing cycle, throwing the paranoid into a projective feedback loop.

The awful and disgusting evil other, who is created from within the self of the paranoid, serves as an objective correlative to stir desire and fantasy deep within the paranoid, who in turn strives to find relief by intensifying the imago of the evil other through more projection. The apocalyptic other is always objectified as the subjective self in this way, becoming in the process a ludicrous tangle of desire, power, and malice.

Strozier’s paranoids experience a sense of fragmentation that closely resembles what some argue is the experience of modernity for many—what Sayid Qutb referred to as the “hideous schizophrenia” that the West insists on inflicting on the world.

But to think in self terms, what we can surmise is that the paranoid’s response to the crisis of fragmentation is a frantic attempt to stave off what he inevitably experiences as the psychological equivalent of death by constructing an alternate universe of imagined dangers populated with projective imagoes of inner experience. That new reality fills in for the old. The new reality is bursting with terror and is not a stable terrain—paranoia, like anxiety, spreads—but at least this new world of malice is familiar.

And, above all, the paranoid is a victim. Part of his megalomania of paranoia is believing that the entire world has nothing better to do with its time than scheme against him. And victimization justifies violence, what Strozier calls the “extraordinary sequence from victimization to violence.”

The paranoid intimately understands the secret world of evil he has created in his projective schemes. His rigid dualistic outlook further removes him from the malice as it loads him with virtue and righteousness. That other becomes, then, the embodiment of evil and not only can but must be dispensed with. In its more extreme cases, when fantasy turns to action, the paranoid feels more than simply an allowance to kill. It becomes an obligation. And, since in the paranoid world one acts on behalf of absolute righteousness, killing becomes healing, as Lifton wrote so eloquently about with the Nazis, or as Aum Shinrikyo, the apocalyptic Japanese cults in the early 1990s, sought in its wild schemes to carry out Armageddon.

Medieval Prologue: Cosmic Christian Anxiety and Global Modern Paranoia

Norman Cohn has laid out the medieval contributions to the Protocols, in particular the pervasive medieval Christian association of Jews with the devil and, by extension, of the Jews as forerunner and agents of the Anti-christ. Jeffrey Woolf explores further elements in this medieval matrix in this volume, some directly linked to this diabolic Jew: the assumption of an undying hatred of Jews for Christians and the tendency to see the Jew not as person but as symbol. In particular, he focuses on the 12th- and 13th-century awakening of Christian thinkers to the development of Talmudic and (later) Qabbalistic thinking among Jews, which fed both their fears and their hatreds.

Here he finds an interesting paradox that sheds light on one of the major hermeneutic problems posed by belief in a patent forgery such as the Protocols (Hagemeister, Mehlman, Berlet). Both the Talmud and the Qabbalah are at once attacked as lies and scanned for proof of Christianity’s truth: The selfsame text embodies both sacred and satanic “truth.” The paradox embodies the deeply contradictory relationship of medieval Christians to Jews, a schizophrenic ambivalence that would only intensify under conditions of Jewish freedom in modern society. As Trachtenberg pointed out long ago, the demonization of Jews reached its height under early modern conditions, in the 16th and 17th centuries, when witchcraft paranoia struck so often, particularly in the modernizing regions of northern Europe, especially in Germany.

In the second chapter on the medieval origins of the Protocols, Johannes Heil explores the ways in which the anti-Semitism of medieval Christians produced narrative lines very similar to the conspiratorial one that lies at the base of the Protocols forgery. Heil starts with the the novel Biarritz (1886), the text that prefigures the shift in antidemocratic conspiracy theory from the evil Masons trying to enslave mankind (ca. 1800) to the evil Jews (ca. 1900). Here, in one of the chapters, we find out that, every hundred years, an intern...