![]()

1

Knowing the Holy Land

Sunday School Lessons and the Six O’Clock News

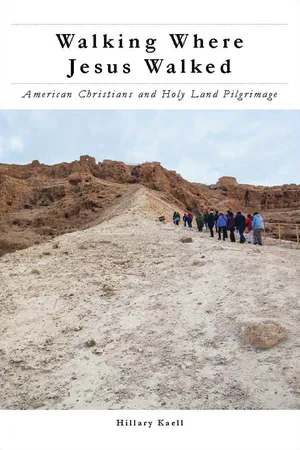

Helen has worshipped at the same Baptist church for fifty years. It is a small red-brick building with a classic white steeple in the countryside east of Raleigh, North Carolina. The main artistic adornment is a wall-length baptistery painting at the front of the sanctuary depicting the Jordan as a wide river with fast-moving rapids in the foreground and majestic mountains in the distance. The bright blue water is flanked by an idyllic green prairie graced with palm trees, a touch of Holy Land exotica.1 The Jordan, as Helen finally saw it in 2009, looks nothing like the image she had known for decades. It is a narrow slow-moving stream with dark greenish water and dense foliage crowding the bank. Instead of mountains, waterfalls, and palms, there is a large modern tourist complex, a souvenir store, and restaurant.

American pilgrims come to the Holy Land familiar with a multiplicity of preexisting images. Writing of nineteenth-century Protestants, historian Hilton Obenzinger identifies an “intertextual layering” of three main influences: the Bible, travel accounts, and millennialist fantasies.2 Generations of Americans have also described Holy Land images infused with sentimental associations gleaned from childhood. Though it was tongue in cheek, Mark Twain’s 1869 travel account gives a sense of the power of these expectations. He was “surprised and hurt,” he writes, upon seeing regular-sized fruit in Palestine: a cherished illustration in his childhood Bible showed the Israelites bearing a “monstrous bunch” of grapes.3

Given how deeply embedded and diffuse Holy Land imagery is, it is not surprising that pilgrims today have trouble pinpointing which particular moments, teaching tools, or visual media influenced them most. They describe biblical images that come from “I don’t know where” or that give them an “odd sense” of recognition.4 They remember poring over Sunday school maps and photos of sand-colored ruins and dressing up in bathrobes and sandals for Christmas nativity plays.5 From nearly every pilgrim, Protestant or Catholic, I heard responses like Loretta’s, a 63-year-old on Pastor Jim’s trip: “I picture it with camels, everyone’s riding a camel or walking. And rocks and dirt and gowns and robes. Everything we had in books when we grew up was camels and sheep and that sort of thing.” However, though they may express certain desires and expectations, to varying degrees all contemporary American pilgrims recognize that such images are constructed (“that’s just media hype” or “I look forward to a more accurate picture”). They are, after all, a generation familiar with a steady stream of often destabilizing Holy Land media. The images they have nurtured since childhood coexist in their minds with newer ones, affected by significant shifts in theology and politics over the last sixty years: Vatican II and the ecumenical dialogue it fostered, “pop” premillennial dispensationalism, and—often looming largest today—the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Figure 1.1. The Jordan River depicted in the baptistery painting at Helen’s church.

Figure 1.2. A photo of the Jordan River baptismal site today. Courtesy of Kathy Martin.

American Holy Land Mania

Among Protestants, “Holy Land mania,” as Obenzinger puts it, dates to the latter half of the nineteenth century.6 It encompassed the development of tourism, such as the Cook’s tours mentioned earlier, but it was much broader too, since the Holy Land was implicated in how American Protestants responded to ideas stemming from the European Enlightenment. When historical criticism raised questions about the authorship and inerrancy of the Bible and the veracity of miraculous events, liberal Christians reacted by adopting a moral hermeneutic based on the human side of Jesus’ ministry. Conservatives defended biblical literalism, formulating a response using Scottish Common Sense philosophy. In its American form, this intellectual current posited that reality—including right and wrong—could be experienced directly through the senses from the material world. For liberals, descriptions of the Holy Land thus added important and edifying details to what was known about Jesus’ earthly life. For conservatives, the geography and ancient artifacts of Palestine seemed to provide scientific, material evidence that biblical events had indeed occurred as written. In both cases, as the heirs of Calvin rejected older notions of sin and predestined salvation, they turned away from God the sovereign to focus their prayers on the loving, profoundly human Son. The resulting theology privileged an immanent deity who walked among the people, whose earthly footsteps mattered, and with whom believers could develop intimate relationships.7

As a result, Americans of all stripes fueled the growing Holy Land industry. Best-selling travel narratives offered detailed accounts of its landscapes, assuring readers that “Palestine is one vast tablet whereupon God’s messages to men have been drawn.”8 Biblical archaeology, a field that developed in the 1840s, unearthed the material traces of past people and places. Illustrated Bibles were filled with carefully wrought imaginings of the biblical world, brought to life through panoramic paintings, photographs, and stereoscopes and, later, cinema. Vacationers at Chautauqua, a famed Methodist educational retreat, could visit Palestine Park, a permanent Holy Land re-creation; those at home might pore over “life of Christ” books, novelistic accounts of Jesus’ everyday life.9 Across ideological and denominational divides, Protestants began to conceive of the Holy Land as the “Fifth Gospel,” and visiting it—an act that would have greatly puzzled their Calvinist predecessors—acquired immense spiritual value.

Today, Protestant pilgrims often remember using Holy Land atlases and maps in Sunday school. Methodist minister and pilgrim John Heyl Vincent, the founder of Chautauqua, wrote the introduction to one of the best-known of such atlases, which went through numerous editions between 1884 and 1951. “Considering the changes which have taken place through all these centuries it would be an easy thing…for men to deny that the people of the book ever lived,” he reminded his readers. “And, if its historic foundation were destroyed, the superstructure of truth, the doctrinal and ethical teachings resting upon it, might in like manner be swept away.” To combat unbelief, students were taught to navigate the atlas’s densely covered maps and memorize its practical guides to Bible life: how to measure a cubit, count in shekels, and learn “difficult old Hebrew names of lands, cities and mountains” through rhythmic chanting.10 Though few pilgrims remember these details today, they recall how such lessons facilitated imaginative journeys with Jesus in his own time: they were taught to picture incidents in the Savior’s home or school life, which were invariably similar to their own, in order to draw moral lessons about how a Christian should behave.11

Biblical archeology was central in these atlases, and today it still features strongly in how Israeli guides lead evangelical tours. Among conservative Christians, especially those of a more intellectual bent, archeology appealed as an Enlightenment science that was understood to serve the interests of faith against historical criticism and Darwinism. It did not hurt that it was also tied to longstanding anti-Catholicism. Protestant criticism was particularly harsh concerning the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, built on the site where the Catholic and Orthodox churches believe Jesus was crucified and buried. Widely read travelogues grimly remarked on the Church’s dirtiness and gaudiness, and the outbursts of violence between resident priests. The sepulchre exemplified the “puerile inventions of monkly credulity,” one nineteenth-century visitor sniffed, and today some evangelicals still dismiss it as the “Church of Bells and Smells.”12

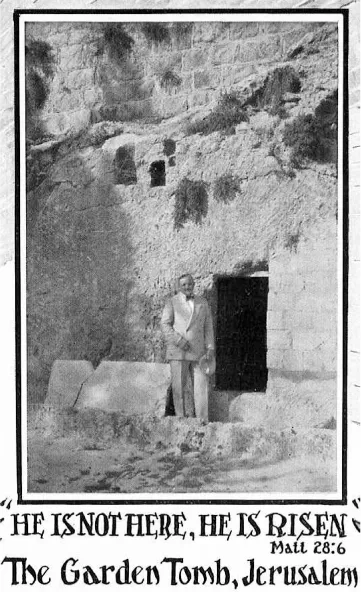

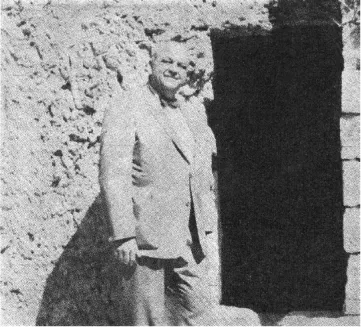

From the 1880s on, Anglo-American Protestants promoted their own site, a quiet spot owned and operated by the English called the Garden Tomb (also called Skull Hill because of its shape or Gordon’s Calvary, after the British general who popularized it). To prove its legitimacy, supporters shored up decades of archeology. William W. Orr, a pilgrim in 1960, wrote about the tomb for Moody Monthly. “Was this really the place of our Lord’s burial?” he asks rhetorically. “Were General Gordon, [archeologist] Sir Charles Marston and many other competent and godly examiners correct in their steadfast conviction that this was indeed the spot?” Orr’s answer is a resounding yes. Photographs of the tomb’s entrance were widely reproduced in magazines, textbooks, and church slideshows. Likely the most extensive early promotion was radio evangelist Paul Radar’s photograph at the Tomb, of which he distributed 15,000 copies across North America.13 Almost all Protestants strike the same pose as Radar did when they visit today.

American Catholics have their own set of Holy Land references, filtered mainly through the Franciscans, the Vatican-appointed custodians of the Holy Land since the fourteenth century. The U.S. Commissariat, which was established in 1882, was careful to defend the authority of traditional sites against Protestant naysayers. Father Godfrey Schilling, the first American Franciscan in residence at the Holy Sepulchre, voiced the Catholic perspective in a review article in The North American Review in 1894:

Figure 1.3. Paul Radar in front of the Garden Tomb, cover image of World-Wide Christian Courier, April 1930.

Believers in the Skull Hill and other new Calvarys and Holy Sepulchres are modest enough to suppose that the Christians and scientists of 1,800 years were all blind and misguided until these new theorists appeared. But, excepting a few curiosity seekers, nobody visits these new sites…and to-morrow we may hear of some other ones made to order to suit the latest ideas of some seeker of novelty and fame.14

Figure 1.4. Moody Monthly correspondent William Orr strikes the same pose in 1960.

Figure 1.5. Tom and Jo Weyrick, an evangelical couple from Minnesota, on a 2007 trip. In an e-mail to family, they captioned this photo, “A sign on the door says, ‘HE IS NOT HERE—FOR HE IS RISEN.’” Used with permission.

Belittling Protestant innovation, Catholics drew instead on a well of romanticized medieval history, made manifest at the Franciscan Monastery of Mount St. Sepulchre in Washington, D.C. Billed as the “Holy Land in America,” its construction was completed in 1899, championed by Father Schilling and fellow Franciscan Charles Vassani. The monastery houses an ornate Byzantine-style church with large reproductions of shrines at the Holy Sepulchre, Nazareth, and Bethlehem. When it was constructed, the front entrance was graced with the coat of arms of medieval Crusader Godfrey de Bouillon; a statue of St. Louis IX, a crusader who was a patron of the Franciscans, still stands inside.15 Until the mid-1960s, the monastery drew 60,000 pilgrims each year who were granted indulgences, asked to remember the 9,000 Franciscan Holy Land martyrs who died of “persecution, plague and pestilence,” and encouraged to donate to the monastery’s ongoing efforts by joining the Holy Land Association.16

These images drew on centuries of battles to wrest control of Holy Land shrines from “infidels” (Muslims) and “Greek schismatics” (the Eastern Orthodox Church), still the largest Christian group in the Holy Land. Even as Catholics such as Schilling defended the Holy Sepulchre against Protestants, they complained that the “Greeks” who controlled most of it were superstitious, dirty, and unreasonable.17 After the 1920s, and through the time when most of the pilgrims were young, the question of Vatican proprietorship of holy places took on a new cast. As Zionism threatened the temporal balance of power, Rome repeatedly released statements that were echoed in the American Catholic press calling for the permanent internationalization of Jerusalem, under the jurisdiction of the (rather ambiguous) “family of nations,” led by the pope.18

Although the triumphalist rhetoric of medieval crusades and martyrs quieted after the Second World War and the establishment of Israel, pilgrims remember that these themes still surfaced during penny collections for the Franciscan missions at Easter and in popular children’s books such as Friar Felix at Large (1950), about a fifteenth-century friar who travels to the Holy Land to battle Muslims and Orthodox priests.19 Most often, though, children’s lessons focused on the Holy Family’s life. Typical of mid-century religious media, Father Francis Filas’s The Family for Families (1947) drew on archeological discovery and historical research (embellished with fictional flourishes) to render in words and illustrations the quotidian lives of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph: what they ate and wore, where they went, how they interacted with each other. Filas’s book went through seven editions by the mid-1950s and today evokes its Cold War milieu. In the preface, Cardinal Cushing, the archbishop of Boston, recommends it for Catholic families beset by “atheistic neighbors,” postwar “paganism,” and the rash of “garish comic books” enthralling America’s youth. Today, Catholic pilgrims often recall these childhood stories about the young Jesus and his family as well as the imagined recreations of his death evoked during devotions such as the Stations of the Cross.20

Theological Shifts since the Second World War

Until the early 1960s, most American pilgrims were mainline Protestants or Catholics and thus believed in some aspect of supersessionist (or replacement) theology. Dating from the second century, this theology states that Jews had forfe...