![]()

1

Introduction

Reframing Chicana/o Art

A certain anxiety accompanies archeological excavation. Besides fearing accidental destruction in the process of discovery, archeologists also worry about the effect of time. Scholars of history and cultural anthropology become similarly anxious when attempting to recover previously lost stories and documents that face a scarcity of opportunities to “speak.” As I researched Chicana/o art since the 1960s, looking for materials that would corroborate the individual memories that I had recorded, I was less concerned about an artist’s inability to recall the past than the fate of the stuff that the artists kept in their basements, garages, and studios. Were moisture, insects, and chemicals destroying precious documents beyond recognition? What if someone decided to trash them before I was granted access? How much more digging would alleviate the fear that I had missed a crucial story?

These anxieties are multiplied when one is working in a field that has been invisible. Compared to other areas of Chicana/o cultural production, the critical examination of the visual arts is largely underdeveloped.1 Awareness of this invisibility produces a “burden of representation,” as Kobena Mercer has observed about black visual arts. He reflects on the burden of getting the entire story told at the first chance because a partial account will not satisfy the urgency of the political moment, an urgency triggered by the cavernous gap in the record. In the end, Mercer urges us to decline this responsibility even though he recognizes that the burden of representation is a product of the “structures of racism” that have “historically marginalized [our] access to the means of cultural production.”2

While I agree with Mercer that the regulation of visibility is a form of institutionalized racism within the public space of museums and galleries and within art history, I am not willing to dismiss the burden of representation.3 If I were to put aside the encumbrance, I would feel as if I were no longer accountable to the histories and structures of racism and other concurrent forms of oppression, sexism and homophobia among them. Contesting hegemony is an ongoing struggle, and the context is too politically charged for me to feel that my choices are merely academic, made in the name of good organization and coherence. If this book appears “particularly anxious” about the recovery of Chicana/o art history, it is because I am keenly aware that the “primary work of cultural excavation” that literary scholar Silvio Torres-Saillant describes is still under way, and that it is an enormous task.4 The pressure to “get it right” is intense because I imagine the potential of equity within the arts.5

I am convinced that Chicana/o art is a distinct category because of its structural location—how it has been, and continues to be, positioned in terms of social contexts and political and economic power. I also recognize that identity-based art is so vilified that it gets dismissed even before it is understood. Thus Chicana/o Remix engages with art critics and art historians who argue that the category of Chicana/o art should be retired because it is no longer relevant in the so-called postidentity moment.6 I join a range of scholars, including Jennifer A. González, Miwon Kwon, Kate Mondloch, and Amelia Jones, who observe that visual arts discourse is still haunted by essentialist models.7 The dispute turns on acceptance of a binary that separates art that is “ethnic” from art that is “universal,” or art that is “political” from art that is “global.” While González and Jones appear more comfortable with the idea that artists participated at one point in “these narrow categorical frameworks,” I am not yet convinced that the majority of Chicana/o artists promoted or practiced “narrow” identities or produced work that activated this binary.8 In addition to challenging mainstream art criticism for its limitations, this book proposes a new and better method of theorizing the artistic production of people of Mexican descent.9 In my refusal to disregard Chicana/o art because it appears troublesome or unfashionable, I address the politics of visibility, allowing me to develop a method that does not appropriate or reify.

The debate among Chicana/o art historians over identity versus postidentity art is, ironically, linked to the ubiquitous dualist taxonomy within Chicana/o art discourse. This discursive coherence is most clearly articulated in earlier writings by Shifra M. Goldman and Tomás Ybarra-Frausto and later by Terezita Romo, Amalia Mesa-Bains, Victor Zamudio-Taylor, and George Vargas, all of whom characterized Chicana/o art in binary terms, dividing it into two periods and styles.10 The first period, 1968 to 1975, is “marked by a totally noncommercial, community-oriented character in the attitudes and expectations of the individuals and groups” who produced the work and in “the purposes they served.”11 Work of this period is often described as political art, agitprop, or people’s art, evoking Maoist principles. The second period, from 1975 to the mid-1980s, is not as neatly specified, but it is generally considered less politically charged and more commercial, arising from individual rather than collective concerns.12 In the late 1990s Ybarra-Frausto introduced a third phase, one dominated by the millennial generation of artists, but it simply continues and reconfirms the waning of political themes and the transcendent importance of the individual that apparently characterized the second period.13 This polarized classificatory scheme gave rise to what has been perceived as a public debate between Shifra M. Goldman and artists Malaquias Montoya and Lezlie Salkowitz-Montoya. Although they appeared to value different aesthetic practices, the Montoyas and Goldman called for a politics of accountability as an aspect of historical and aesthetic recognition, or the more current term, visibility. They called on artists to engage in the struggle against multiple forms of oppression, although the Montoyas emphasized capitalism.14 For them, artists are agents of social change. As Romo notes in one of her reformulations of the dualist methodology, the Montoyas advanced “agency (action)” as the defining aspect of Chicana/o art, rather than “artwork (object) and intent (message),” which had been the focus of previous scholarship.15

I do not take issue with the claim that Chicana/o art challenges the notion that art is autonomous—that its meaning is internal, referring only to the work itself (“art for art’s sake,” perhaps). But in this book I do intervene to argue against the dualist approach, which has generally ruled Chicana/o art history since the mid-1970s. I am especially interested in what is left out when one relies on a binary taxonomy of Chicana/o art and in how its dualistic terms of representation narrow the interpretation, reception, and documentation of Chicana/o art. Chon A. Noriega offers a partial lesson about this bifurcating methodology in his observation of “touchstone Chicano art surveys since the 1980s.” He states that “curatorial binaries” have supported a narrow interpretation of Chicana/o art that contrasts “cultural politics versus art market” orientations and “conceptual versus realist” styles.16 I extend Noriega’s observation and expose not only the cultural politics of institutional and exhibition settings but also the ways the methodology of Chicana/o art history has consistently turned to a binary to characterize Chicana/o art and artists in the following ways: political versus commercial art, folk versus fine art, parochial versus cosmopolitan art or global aesthetics, representational versus conceptual art, older or veterano artists versus younger ones, women versus men, feminist versus Chicano art (in this case, the authentic category is structured as patriarchal), historical documents versus aesthetic objects, untrained versus formally trained artists, ethnic-identified versus postethnic artists, and Chicana/o versus Mexican artists. The polarities are coupled so that the existence of one requires the existence of the other. Often, however, that other is assumed or imagined: the opposing category is rarely present within an exhibition or scholarly work.17 The most troubling aspect of the binary is its ability to excuse serious research.

My burden of representation is to repair the “entrenched, polarizing accounts” and explain how Chicana/o art “might bridge or even exceed these categories.”18 Thus my goal in Chicana/o Remix is to challenge the art historian, curator, or critic who has classified Chicana/o art as parochial, separatist, political, “too ethnic,” or not ethnic enough. In presenting this new scholarship, I hope to broaden the ways Chicana/o visual art is interpreted and theorized and to expand the arenas in which critical debate takes place. Read comparatively with the existing scholarship, this book offers a revision of accepted Mexican, Latin American, and American art histories, one built on a broader, more representative base that does not conform to normative phantoms. I do so by documenting the multifaceted, intertwined, and generative visual culture of Chicana/o art in Los Angeles since 1963.

Los Angeles serves as an ideal case study for investigating Chicana/o art and its terms of visibility for several reasons. The metropolitan area may not be unique in the quality and quantity of its Chicana/o visual arts, but it is exemplary in the resources and collective energy that can be harnessed for its documentation. Los Angeles is home to three major centers of Chicana/o art production and criticism—Self Help Graphics & Art, Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC), and Plaza de la Raza—that originated during the Chicano movement and continue a sustained and expansive engagement with the visual arts. Los Angeles is also one of only a few urban centers with a rich material archive. The region allows for extensive archival investigation of its own history, thanks to the private collection of postcards and other exhibition ephemera gathered and preserved by Mary Salinas Durón and Armando Durón, the archival materials, art, and life history interviews of artists at the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center, and the California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives (CEMA) at the University of California, Santa Barbara, which houses the institutional materials of multiple arts organizations located in Los Angeles and the private files of Shifra M. Goldman.19

Los Angeles has been home to some of the most important exhibitions of Chicana/o art, and these have given rise to extensive archival documentation and popular criticism. The foundational show Chicano Art: Resistance and Affirmation, 1965–1985 emerged in 1990 from faculty and students at UCLA. The metropolitan area is home to internationally recognized Chicana/o artists, including Carlos Almaraz, Judith Baca, Chaz Bojórquez, Barbara Carrasco, Yreina D. Cervántez, Harry Gamboa Jr., Gronk, Gilbert “Magu” Sánchez Luján, John Valadez, and Patssi Valdez. Their work is exhibited, collected, documented, and archived, although not at the level of other midcareer American artists.

The most recent phenomenon that makes Los Angeles important is the unprecedented season in which six exhibitions of Chicana/o art were produced by mainstream institutions with support from the Getty Foundation’s Pacific Standard Time (PST) initiative.20 Starting in 2002, the Getty provided over $11 million to support research, exhibitions, programs, and publications on the LA postwar art scene. This initiative launched an unparalleled six-month collaboration with over sixty institutions that presented the art of Los Angeles in a series of public programs and exhibitions that began in the fall of 2011. Six of the exhibitions focused on Chicana/o art. Asco: Elite of the Obscure was curated by Rita Gonzalez and C. Ondine Chavoya and was presented by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) with the Williams College Museum of Art. MEX/LA: Mexican Modernism(s) in Los Angeles 1930–1985 was curated by Rubén Ortiz-Torres (with Jesse Lerner) at the Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach. The umbrella project L.A. Xicano, organized by the Chicano Studies Research Center, presented four exhibitions: Art along the Hyphen: The Mexican-American Generation (lead curator, Terezita Romo) at the Autry National Center; Mural Remix: Sandra de la Loza, an installation conceived and designed by the artist at LACMA; and, at UCLA’s Fowler Museum, Mapping Another L.A.: The Chicano Art Movement and Icons of the Invisible: Oscar Castillo. PST represented a milestone in the United States, not just Los Angeles.21 The exhibition of Chicana/o art in Los Angeles has often involved joint efforts between community-based or artist collectives, college- and university-based programs, and mainstream institutions. For instance, the 1975 coproduced group show Chicanismo en el Arte debuted at East Los Angeles College and LACMA and involved a large cohort of Chicana/o artists and arts advocates. The quality and quantity of exhibitions that are generated by collaborations or debates between Chicana/o arts cultural centers and mainstream institutions are probably unique to Los Angeles, and create an extensive discursive and institutional archive.

Chicana/o Remix also elucidates the analysis of Chicana/o, Latina/o, and Latin American art beyond Los Angeles. Forms of and approaches to art are not unique to Chicana/o Los Angeles but are also found among Nuyorican artists in New York City, Mexican artists in Chicago, and Tejana/o artists in San Antonio. The troubled relations between Los Angeles mainstream art museums and community-based arts organizations—the debates, the tensions, and the uneven collaborations—apply to other sites of Latina/o cultural production. Most important, although the critical frames for visibility emerge from Los Angeles–based exhibition and curatorial practices, the amalgamated theoretical discourse can apply across a range of Chicana/o art cultural production. Los Angeles does not hold a monopoly on the use of exhibition and curation as a site of art criticism or as a methodology for canon critique. In this way, the book contributes to an understanding of Chicana/o and Latina/o art that is based on a broader national and international perspective.

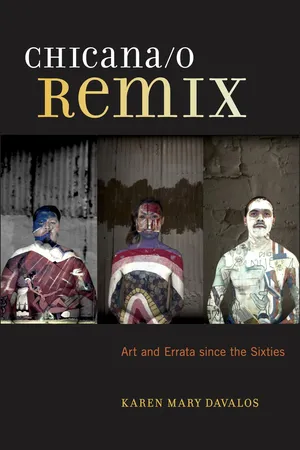

The Wisdom of Action Portraits

I begin my project with an analysis of Sandra de la Loza’s Action Portraits (2011). This groundbreaking work, which de la Loza created in collaboration with Joseph Santarromana, visually expresses the methodology and framework for my engagement with Chicana/o art. Simply put, de la Loza brings to the foreground of art discourse previously ignored or undocumented styles of Chicana/o murals painted in the 1970s. In her “double role as artist and curator,” she functions as a “performative archivist” who instructs us to return to the archive with eyes wide open.22 A component of the exhibition Mural Remix: Sandra de la Loza at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) in 2011, Action Portraits covered an entire wall of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation Gallery on the second floor of LACMA’s Ahmanson Building. In the three-channel video installation, six contemporary East Los Angeles muralists—identified as Fabian Debora, Roberto Del Hoyo, Raul Gonzalez, Liliflor, Sonji, and Timoi—are shown larger than life, painting their nude bodies with kaleidoscopic designs. Each muralist works methodically and somewhat theatrically, moving a large paintbrush over torso, arms, hands, neck, and face. As the brush moves, multichromatic patterns appear on the skin. De la Loza created these designs from samples drawn from color slides in the Nancy Tovar Murals of East L...