![]()

1

Liberating Free Labor

Vere Foster and Assisted Irish Emigration, 1850–1865

Introduction: Assistance, Relief, Control

Assisted emigration accounted for less than 4 percent of departures from Ireland during the nineteenth century. Nonetheless, the roughly 275,000 people who left the island after receiving financial aid from landlords, the British state, or private philanthropists deserve attention as cases that demonstrate how the redistribution of underemployed surplus labor was governed and imagined as a resource for white, Anglophone settlements.1 Bracketed by the Irish Famine and the beginnings of mass migration to the United States, and the Civil War, the period of 1850 to 1865 saw key developments relating to what it meant to be a free laborer and migrant if one was a young, unaccompanied Irish woman. By the end of the war, Irish servants were avidly pursuing the benefits that came with the ability to contract their labor freely, much to the dismay of Anglo-American employers. In conflict with the prescriptions that the brokers of their labor offered, which urged them to move west into the interior and marry, Irish servants crafted racial and political identities as independent, urban wage earners instead.

* * *

Mary Harlon had strong opinions about wages, working conditions, and the respect she deserved as a domestic servant. Contrary to what might be expected of an Irish orphan whose emigration was paid for by charitable funds, Harlon was hardly a dependent. Between May 1862 and October 1865, she shared her perspectives on work and life in a series of six letters she wrote to Vere Foster, the man who sponsored her immigration. Foster was a member of the Anglo-Irish gentry. Using his personal inheritance and private donations solicited through his Pioneer Irish Emigration Fund, Foster financed the passage of approximately 1,250 Irish women between 1850 and 1857. During the early 1880s, Foster subsidized the emigration of an additional 20,000 women between the ages of eighteen and thirty, paying for half the cost of their steamship tickets.2 The Foster family had been landlords in County Louth, Ireland, since the late eighteenth century, and most of the emigrants who applied for assistance in the 1850s came from the area around Glyde Court, the family’s estate. Foster appears to have been an acquaintance of Harlon’s parish priest, who probably connected the two. In her letters, Harlon asked Foster to relay to a Father Smyth that she was attending Mass every Sunday, and that she received communion whenever her work schedule allowed.

Foster was a critic of private and state-backed initiatives that dispensed charity without calculating what returns their investment might bring.3 Influenced by the emerging social science of charity work in Britain, Foster’s solicitations for financial support included the controversial proposal calling for prohibitions on the emigration of families, which landlords could finance as an alternative to paying taxes that supported local workhouses and outdoor relief. Foster believed that the migration of whole families increased the likelihood of pauperism, and that it was prudent to identify the most capable individual wage earners when administering emigration assistance.4 Because the arrival of pauper families also aggravated nativist public opinion in the United States, their emigration endangered the trust on which more productive transfers of populations between nation-states rested. Framing migration as the trade in human subjects, Foster noted that his program was designed to minimize the possibility of “some trifling misunderstanding between the governments of the two most free and progressive countries on the globe.”5 The migrants Foster sponsored were asked to repay the assistance they received, although no data exist on how many actually did. In Harlon’s case, she would have had no difficulty reimbursing Foster’s “loan.” In May 1862, Harlon’s situation with the Carrigan family came to an abrupt end. To Foster, Harlon vented anger at having spent seventeen months working for the Carrigans only to be let go with one day’s notice. She was upset that the Carrigans had provided no explanation as to why she was dismissed, since her service—to the best of her knowledge—had been exemplary. Her disappointment notwithstanding, Harlon had managed to put away eighty dollars in savings and found new employment, with the Taylor family, almost immediately.

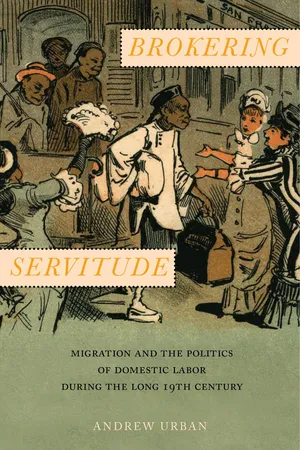

In defiance of the thrift that Foster preached, Harlon communicated her plans to purchase a new silk dress.6 This act of personal indulgence was perhaps intended to numb the sting of her sudden dismissal. It can also be read as an assertion of her continued autonomy. Clothing was a frequent flash point in conflicts between Irish servants and their Anglo-American employers. In the 1850s, middle-class employers were already complaining that Irish servants wasted their wages on unneeded and unbecoming consumer luxuries. When dressed in fine clothes, an Irish servant challenged the visible markers of class difference that separated capital from labor, and immigrants from the native-born. An 1863 cartoon in Harper’s Weekly gave visual form to employers’ anxieties, and the ways in which fashion and Irish servants’ liberty of contract had become conflated. In the image, “Bridget O’Flaherty” wears a dress with a large bustle and sports an ornamental umbrella while she awaits hire in an intelligence office. The office’s proprietor, Mrs. Blackstone, presents to O’Flaherty a “Mr. Jones,” who is looking for a cook and assures his prospective domestic that he has a “fair character” and is “steady.” Harper’s readers would have appreciated the irony. It is Jones getting scrutinized rather than the other way around.7

Figure 1.1. “The Present Intelligence Offices,” Harper’s Weekly, 1863.

The Catholic Church and middle-class employers were in agreement that Irish servants had no business concerning themselves with personal appearance, albeit for different reasons. Sister Mary Frances Cusack lectured in Advice to Irish Girls in America that the servant who bought “fine clothes, which are not suitable to her station in life,” put “herself in danger both in this world and the next.” Cusack was undoubtedly also worried that individual purchases would cut into the amount of remittances that Irish women were able to send back to Ireland. In this vein as well, Irish Catholic commentators sometimes dissuaded single women from marrying, since marital obligations—and the need to keep their own homes—hindered their ability to earn wages.8

There is an insular quality to Harlon’s correspondence that gestures to ways in which immediate material concerns dominated the perspective of the immigrant wage worker. Written during the Civil War, her letters contain only passing mentions of the conflict. The New York City Draft Riots, which led some Anglo-American employers to allege that their Irish servants were plotting to loot their workplaces, merit no attention at all. The only biographical details Harlon provides in her letters are references to two brothers still in Ireland, and a one-line lament about the “loss” of her parents.9 Harlon frequently prayed for Foster in order to express her “gratitude” for his “kindness,” and concluded her letters with the valediction “your friend and servant.” Deference coexists with an intimate and open tone in which Harlon appears almost indifferent to the chasm of social class between the two. Foster responded to the correspondence he received from Harlon—although the copies of his letters are unavailable—and she mentions in one of her letters that he called on her in person when he visited New York in 1864.10

Much more is known about Foster, unsurprisingly. Born in 1819 in Copenhagen, Vere spent his youth in Turin, before enrolling at Eton and then Oxford. His father, Augustus John Foster, was a career diplomat who served as minister plenipotentiary (the equivalent of ambassador) to the United States before vacating his position at the start of the War of 1812. Vere, if he set foot on Irish soil at all before 1847, left no record of having visited. Both he and his eldest brother, Frederick, pursued careers in diplomacy following their father, while the middle of the three brothers, Cavendish, became an Anglican minister. When Augustus committed suicide in 1848, Frederick took charge of Glyde Court. After touring famine-ravished southern and western Ireland in the autumn of 1849, Vere enrolled at the Glasnevin Model Farm School outside of Dublin, to study how to better manage his family’s lands and tenants through modern farming techniques. He anticipated serving as his brother’s estate agent.11 While still enrolled at the Glasnevin School, Vere used a portion of his personal allowance to fund the passage of forty emigrants from County Louth, whose “character and industrious habits” he had vetted through interviews with police and clergy, a method that he would adopt as standard.12 For reasons unknown, in 1850 he decided to abandon his plans to serve as estate agent in favor of pursuing assisted migration as a form of philanthropic social work, and, for the next decade, his primary vocation.

Foster was enamored of areas of the United States that existed beyond the Appalachian Mountains but east of the Mississippi River. In his opinion, these were the destinations where Irish migrants could best prosper. To Foster, the ideal course for an Irish woman he sponsored had her leave Castle Garden without delay for states such as Illinois and Wisconsin. Harlon disregarded this advice, although she did not reject job mobility outright. When she wrote to Foster in June 1864, she informed him that she was contemplating a move to California. Cheekily, she explained that she had decided not to go because he had once told her that the state was too distant for him to visit. A month later, Harlon again raised the possibility of relocating to California. She was no doubt tempted by the high wages for servants on the Pacific Coast, which averaged between twenty and twenty-five dollars per month compared to the ten dollars she could earn in New York City.13 Still, the journey to San Francisco took a month or more and in 1864 could be accomplished only by boat and then railroad across the Isthmus of Panama. The trip was expensive and fraught with health risks, and ended in an unfamiliar place. Nor was there any guarantee that work would be as readily available and well-compensated as she had heard.

Irish wage laborers were understandably daunted by the upfront capital investment that secondary migrations required, and individuals like Foster, similar to commercial brokers, staked their authority on being able to intervene and help overcome this obstacle. Visiting California in 1867, Charles Loring Brace, the founder of the Children’s Aid Society, estimated that female domestics in San Francisco made on average three times more than the monthly wages paid to their counterparts in eastern cities and that ambitious women could enter into contracts where employers paid the cost of their passage to San Francisco.14 In 1869, the Dublin-based Freeman’s Journal published an advertisement from an unnamed San Francisco company that offered to pay Irish women a hundred fifty dollars in gold for a year’s work and to cover the expensive, lengthy journey. Receipt of the full sum was contingent, however, on the contracted servants’ remaining at their jobs for a year.15 As these offers indicate, Foster competed against other brokers who had commercial incentives to try to recruit white servants to areas where labor shortages existed. In New York, Harlon had the ability to earn steady wages while healthy. Not having to pay for rent or board, she kept her expenses minimal. She gave no indication that she supported her brothers with remittances. The city abounded with job opportunities for experienced servants like Harlon. In her June 1864 letter, Harlon inquired as to whether Foster had “herd of a place to sute me better.”16 She continued to view Foster as an intermediary who might be called on to assist her, albeit through references rather than immediate material support.

When the Taylors refused Harlon’s request for a raise in August 1864, she responded to a newspaper advertisement seeking a servant willing to accompany a woman to Key West, Florida, and to work there at a salary of twelve dollars a month. Whether wanderlust or higher wages enticed Harlon to go “out South,” as she put it, this was a speculative move on her part. In Key West, Harlon was employed by Walter McFarland and his family at Fort Zachary Taylor, a base in the Union’s naval blockade. In a letter to Foster dated December 20, 1864, Harlon described falling seriously ill upon her arrival in Key West—malaria had long plagued the base—which had forced her to spend a long period convalescing. Whether or not she received pay while recovering was not stated; if she was not working, wages were not guaranteed. At the McFarlands’ house, Harlon’s only companion was a hired black freeman who did occasional work around the home. She lent him books and tried to teach him to read.17 Melancholy permeates the letter. Relegated to the social margins of the household, Harlon felt “all alone.” Her vulnerability is a subtext to the letter. If illness returned, who would look after her and ensure that she got back to New York City?

Harlon made it back to New York, her health intact. October 1865 found her writing from Litchfield, Connecticut, where her wealthy New York employers, the Whites, kept a second home. Upon returning to the city, Harlon had stayed with the Corcoran family, whom she described as her first employers in the United States. The Corcorans, their name suggests, were probably Irish Catholic. Whereas the McFarlands treated Harlon as a servant to be grouped with the rest of the hired help, the elderly Mrs. Corcoran viewed her as a member of the extended family deserving of free lodging while she looked for work in the city. Harlon’s economic success as an independent wage earner led her to be disinterested in marriage. She turned down the engagement proposal of a suitor, telling Foster in her October letter—in a flirtatious tone—that a man of his class and intellect was the only type she wanted to wed.18 This was the last letter from Harlon that Foster archived.

* * *

From the colonial era onward local policies had required shipmasters transporting immigrants to indemnify municipalities and states against having to provide public relief toward the care...