![]()

1

That Which Survives

Design Networks and Blueprint Culture between Fandom and Franchise

The 2009 release of J. J. Abrams’s Star Trek reboot marked a significant turn in the fortunes of the aging media property. The eleventh feature film in the series was the first to recast the iconic central roles of James T. Kirk, Leonard McCoy, Spock, Sulu, Uhura, and the rest of the bridge crew with younger actors, while updating the pace and tone of the story with an energetic, action-oriented approach that differed markedly from previous installments. Helmed by a professed outsider to Trek fandom, Abrams’s “reimagining” was widely (though not unanimously) judged a success, earning the highest box-office returns of any Trek movie to that point, and spawning two sequels to date, Star Trek Into Darkness (2013) and Star Trek Beyond (2016). But securing a future for the franchise required more than a simple facelift. It was just as important that the fan-dubbed “NuTrek” pass the loyalty test of longtime viewers—some of whom had been devotees since the late 1960s—as it was to welcome fresh and unfamiliar audiences. The Trek reboot adopted multiple strategies to assure fans that it was, despite the liberties it had taken, a bona fide addition to canon. Chief among these was a time-travel plot that revolved around the creation of an alternate reality, the Kelvin Timeline, enabling the archive of previously established adventures to remain valid in both industrial and fannish imaginaries.

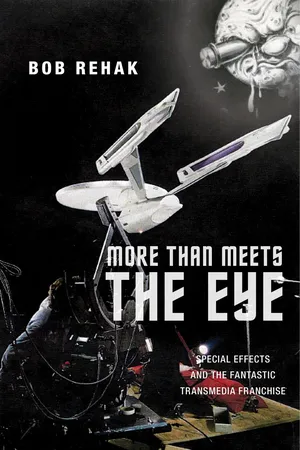

More important than any metanarrative contortion, however, was what the production sought to achieve on a stylistic, visual level. Key elements of the Star Trek franchise’s trademark visual vocabulary, from the command insignia worn by officers and crew to the U.S.S. Enterprise itself, pervaded Abrams’s film in modified but recognizable forms [Figure 1.1]. These elements forged links both at the level of the brand—where they marked the new movie as a member of the franchise—and at the level of the diegesis, where they signaled that the story’s events were taking place in the same universe of “hardware” (albeit an interdimensional variant) that fans had engaged with for decades. The design allegiances connecting the rebooted Trek to the Trek of old illustrate a process that has helped make the franchise a viable transmedia presence for nearly half a century.

Figure 1.1. The rebooted Enterprise of Star Trek (2009), repeating the Original Series ship design with a difference.

This chapter explores the ongoing manufacture of Trek-related objects and imagery in a range of media, based on what I will call a design network: an open-ended yet rigorously specific canon of stylistic elements infused with narrative significance. In “That Which Survives,” an episode that aired in 1969 during the third season of the original Star Trek, Kirk and his crew encounter a computer program in the guise of the beautiful Losira (Lee Meriwether), who guards the remnants of a long-dead civilization.1 A holographic projection, Losira manifests in as many versions as there are crewmembers, telling each, “I am for you.” Her iterative nature, retaining recognizability from instance to instance while adapting to the desires and identifications of a changing audience, captures the essence of the design network: literally that which survives from one episode, series, and medium to another, organizing production, regulating difference, and ensuring brand identity in the face of potentially disruptive transitions. Simply put, it is the principle by which Star Trek manufactures more of itself—DNA of the fantastic transmedia franchise. As Heather Urbanski notes in her study of science-fiction reboots, technologies of visualization in the digital age have become important tools not just for updating but for expanding on and evolving the look of successive installments in a given franchise.2 I would go further: special effects, understood in their broadest sense as a constellation of practical, optical, and digital techniques for bringing unreal worlds into existence, have from the start of the modern blockbuster era been essential to the establishment and growth of design networks, which together constitute a virtual universe while mediating the industrial and popular investments—linked spheres of production and reception—that maintain it.

Design networks like Star Trek’s are central to the growth and maintenance of the modern hyperdiegesis: “a vast and detailed narrative space, only a fraction of which is ever directly seen or encountered within the text, but which nevertheless appears to operate according to principles of internal logic and extension.”3 In the years since Matt Hills introduced this concept in relation to cult texts, hyperdiegeses or storyworlds have become an area of fervent interest in studies of convergence culture and transmedia storytelling, which focus on the industrial production of fictions across a range of media formats, including movies, television, comic books, and games played on tabletops and computer screens.4 The concept of sprawling fictional settings whose fundamental unreality is counterbalanced by systematic continuity is not exclusively the province of contemporary media, of course, but dates back thousands of years, from some of humankind’s originary myths to its most revered works of theater and literature. Mark J. P. Wolf’s Building Imaginary Worlds contains an appendix with hundreds of entries ranging from the Island of Atlantis in Plato’s Timaeus in 360 BC to Jonathan Swift’s satirical creations Lilliput and Brobdingnag (1726), Lewis Carroll’s Wonderland (1865), Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Pellucidar (1914), and William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County (1929).5 With the exception of the last, most of these examples reflect the truism that alternate worlds of fiction tend to be unusual and exotic—precisely the kinds of places one does not encounter in daily reality—and hence an especially fertile ground for genres of the fantastic such as science fiction, fantasy, and horror. Our current transmedia landscape is studded with storyworlds both longstanding (Tolkien’s Middle Earth) and of recent vintage (Hogwarts and environs in J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series), the details of their settings supplied by textual description as well as artists’ illustrations, maps, blueprints, and other reference materials.

Yet the activity of creating, maintaining, and expanding the storyworlds of fantastic transmedia through cartographic or encyclopedic paratexts is not just the province of the franchise’s producers and owners. Audiences of design-oriented fans—in particular, members of what I call “blueprint culture”—have played a vital role in taking the materials offered by official production sources and elaborating on them to fill in gaps, explain contradictions, and connect dots, building stable, consistent frameworks from the inevitably partial and fragmentary pieces doled out by the media industry. Generally less interested in character interaction and psychological relationships than in a fictional universe’s contents—biographies, geographies, political and economic systems, and most of all hardware such as buildings, vehicles, technologies, and weapons—design-oriented fans are avid students of canon (the given “facts” of the fiction). In their epistemological stance as well as in the type of textual and physical materials they create, such fans thus seem to differ from those who have been the traditional focus of fan studies, such as slash writers and video makers.6 This difference has been codified with the labels “transformational” and “affirmational”: transformational fans refashion the franchise text to reflect their own concerns and predilections, producing creative work that implicitly comments on and critiques official content, while affirmational fans seek to reinforce and elaborate on canon.7 In suggesting the term “mimetic fandom” as a third option, Hills critically highlights the legitimizing effects of this way of categorizing fan activity, pointing out the underlying “oscillatory” movement between canonical allegiance and transformative potential in almost every mode of fannish engagement.8

Focusing on the case of Star Trek—in particular, its genesis as a television show in the 1960s and subsequent transformations into a fan phenomenon and film franchise in the 1970s and early 1980s—brings to light the centrality of special effects to creating a canonical storyworld and building on it over time. This occurs through economically and industrially driven dynamics of repetition and reuse, often in the form of “bottle shows” (episodes taking place mostly or entirely aboard the Enterprise) that grant sustained exposure to the storyworld’s most distinctive elements. Moreover, the case of Star Trek invites us to see the production and reception of those elements as an ongoing creative and critical dialogue between official and unofficial authors, working together—not always in cohesive or friendly fashion—to forge a shared, collective fictional property and corresponding cultural investments. Star Trek brings to light linkages among transformational, affirmational, and mimetic modes of fandom that work in perpetual, productive negotiation to shape franchise development: neither simply accepting official output in a state of mindless acquiescence, nor continually pushing back by “rereading and rewriting” that content against the grain, but instead engaging with and, in a real sense, co-authoring it over time.9 From its birth in the broadcast-television era of the 1960s to the proliferating series, reboots, and sophisticated fan productions of its more recent incarnations in digital and streaming media, Star Trek’s design network—along with the design-oriented fans who parse, contest, and contribute to it—have built a bridge between today’s transmedia storytelling systems and the fledgling franchises that were its analog-era forebears.

Designing Star Trek, 1964–1969

The Original Series of Star Trek has been described as “the most successful failure in the history of television,” because its relatively brief network run stands in ironic contrast to decades of persistence as a fixture of popular culture and revenue source for its license holders.10 By 1991, twenty-five years after its premiere, the series had been in syndication continuously, spawning feature films, spinoff series, “novels, books, videotapes, audiotapes, records, computer games, and a countless number of merchandising tie-ins, [becoming] an international phenomenon. There are hundreds of Star Trek fan clubs and conventions around the world where fans … gather with others who share their interest in the program.”11 In the quarter century since then, the franchise has only continued to expand, adding new television series, feature films, video games, novels, and comics, along with sophisticated fan productions such as Star Trek: Phase II and Star Trek Continues, which I discuss later in this chapter.

Explanations of Trek’s popularity typically center on the show’s optimistic portrayal of a future where tolerance and equality reign. As Gene Roddenberry said in 1968:

Intolerance in the 23rd century? Improbable! If man survives that long, he will have learned to take a delight in the essential differences between men and between cultures. He will learn that differences in ideas and attitudes are a delight, part of life’s exciting variety, not something to fear. It’s a manifestation of the greatness that God, or whatever it is, gave us. This infinite variation and delight, this is part of the optimism we built into Star Trek.12

While noble, Roddenberry’s sentiment fails to account fully for Star Trek’s continued ubiquity—particularly when contrasted with the many films and TV series, made with similarly progressive and humanistic messages, that failed to launch multimedia empires or win the loyalty of a worldwide fan movement. At least as important as ethos, storyline, and character are the elements of visual design that constitute Trek...