- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

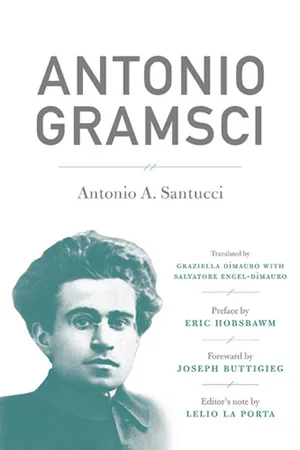

Antonio Gramsci

About this book

“What the future fortunes of [Gramsci’s] writings will be, we cannot know. However, his permanence is already sufficiently sure, and justifies the historical study of his international reception. The present collection of studies is an indispensable foundation for this.” —Eric Hobsbawm, from the preface

Antonio Gramsci is a giant of Marxian thought and one of the world's greatest cultural critics. Antonio A. Santucci is perhaps the world's preeminent Gramsci scholar. Monthly Review Press is proud to publish, for the first time in English, Santucci’s masterful intellectual biography of the great Sardinian scholar and revolutionary.

Gramscian terms such as “civil society” and “hegemony” are much used in everyday political discourse. Santucci warns us, however, that these words have been appropriated by both radicals and conservatives for contemporary and often self-serving ends that often have nothing to do with Gramsci’s purposes in developing them. Rather what we must do, and what Santucci illustrates time and again in his dissection of Gramsci’s writings, is absorb Gramsci’s methods. These can be summed up as the suspicion of “grand explanatory schemes,” the unity of theory and practice, and a focus on the details of everyday life. With respect to the last of these, Joseph Buttigieg says in his Nota: “Gramsci did not set out to explain historical reality armed with some full-fledged concept, such as hegemony; rather, he examined the minutiae of concrete social, economic, cultural, and political relations as they are lived in by individuals in their specific historical circumstances and, gradually, he acquired an increasingly complex understanding of how hegemony operates in many diverse ways and under many aspects within the capillaries of society.”

The rigor of Santucci’s examination of Gramsci’s life and work matches that of the seminal thought of the master himself. Readers will be enlightened and inspired by every page.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

APPENDIX I

Biographical Chronology of Antonio Gramsci

1891 |

Born in Ales, near Cagliari, January 22. |

1911 |

Graduated from Lyceum in Cagliari; in November he enrolls at the Department of Literature, University of Turin. |

1913 |

Joins the socialist section of Turin. |

1915 |

On December 10, joins the Turin editorial staff of Avanti! |

1917 |

Continues his journalistic activity and becomes director of Grido del Popolo [The People’s Cry]. Elected secretary of the temporary executive committee of the socialist section of Turin. |

1918 |

Grido del Popolo ceases publication. |

1919 |

With Tasca, Terracini, and Togliatti, he founds Ordine Nuovo [New Order]. The first issue appears on May 1st. |

1920 |

In September, he takes part in the factory occupation movement. On December 24, the last issue of the weekly Ordine Nuovo is printed. |

1921 |

On January 1st, the first issue of the daily Ordine Nuovo, organ of the Turin Communists, appears. On January 21, he is elected member of the executive committee of the Italian Communist Party, formed the same day in Livorno. |

1922 |

In March, he is elected to represent the party in the executive committee of the Communist International. On March 26, he leaves for Moscow. In June, he participates in the Second Congress of the International. He is admitted to a clinic in Moscow, where, in September, he meets his future wife, Julia Schucht. |

1923 |

During his stay in Moscow, the Italian police issue a warrant for his arrest. On December 3, he arrives in Vienna, elected by the International’s executive, and tasked with maintaining contacts between the Italian Communist Party and other European Communist parties. |

1924 |

On February 22, the first issue of l’Unità [Unity] is printed in Milan. The third series of Ordine Nuovo, now a fortnightly publication, is printed in Rome beginning March 1. On April 6th, he is elected deputy in the Veneto constituency. He returns to Italy on May 12. In August, his son Delio is born in Moscow. |

1925 |

In January, he meets Tatiana Schucht, Julia’s sister, in Rome. He takes part in the 5th Session of the International Executive in Moscow in March and April. |

1926 |

In January, he participates in the 3rd National Congress of the PCI in Lyon. Julia gives birth in August to a second son, Giuliano, in Moscow. On November 8, despite parliamentary immunity, he is arrested and imprisoned in Regina Coeli. On November 18, he receives a five-year sentence of solitary confinement. On December 7, he arrives on the island of Ustica. |

1927 |

On January 14, the military court of Milan issues a warrant for his arrest. He leaves Ustica on January 20, and on February 7 he is sent to San Vittore prison. |

1928 |

On March 19, he is tried by the Special Court. On May 11, he leaves for Rome and the following day is imprisoned at Regina Coeli. On May 28, the trial against the leadership of the PCI starts. On June 4, he is sentenced to twenty years, four months, and five days in prison. On June 22, he is assigned to the special prison in Turi, near Bari, where he arrives on July 19. |

1929 |

On February 8, he begins to write the first of his Prison Notebooks. |

1931 |

Already severely ill, in August he is affected by a serious health crisis. |

1932 |

Following amnesty measures, his sentence is reduced to twelve years and four months. |

1933 |

On March 7, he is struck by a second serious health crisis. In July, he asks Tatiana to initiate a petition for his transfer to the infirmary of another prison. The petition is accepted in October and, on November 19, he leaves Turi and is temporarily assigned to Civitavecchia. On December 7, still under arrest, he is admitted to Doctor Cusumano’s clinic in Formia. |

1934 |

He forwards a request for conditional freedom, which is granted on October 25. |

1935 |

In April, he asks to be transferred to a private clinic in Fiesole (near Florence). In June, he suffers a third health crisis. On August 24, he leaves Cusumano’s clinic and is admitted to the Quisisana clinic in Rome. |

1937 |

With the end of conditional freedom in April, his full freedom is restored. On April 25, he suffers a cerebral hemorrhage. He dies on April 27. The funeral takes place the day after. His ashes are buried at the Verano Cemetery in Rome and, following liberation, transferred to the Protestent Cemetery. |

APPENDIX 2

Biographies of Main Political Figures

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Foreword

- Editor’s Note

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- The Political Writings

- The Letters from Prison

- The Prison Notebooks

- End-of-Century Gramsci

- Appendix 1: Biographical Chronology

- Appendix 2: Biographies of Main Political Figures

- Notes

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app