![]()

Part 1

Space

People cut themselves off from their ties of the old life when they come to Los Angeles. They are looking for a place where they can be free, where they can do things they couldn’t do anywhere else.

—Tom Bradley

Reality is wrong. Dreams are for real.

—Tupac Shakur

![]()

Chapter 1

Race, Space, and the Evolution of Black Los Angeles

Paul Robinson

First elected in 1973, Tom Bradley is usually credited as the first black mayor of Los Angeles. But a more comprehensive history of the city must recognize that Francisco Reyes was actually the first. His term began in 1793, when the city was still under the Spanish flag. To be sure, the African presence in Los Angeles dates back to the city’s origins, and the story of the “Black City of Angels” has yet to be fully told. In this opening chapter, we journey through time to “map out” the spaces associated with the evolution of Black Los Angeles.

African Roots

Although there has long been recognition of the mixed Spanish, African and Native American origins of the first settlers in Los Angeles, there also has been a tendency for scholars to downplay the influence of their African and Native American roots, instead dwelling on their assimilation into the region’s Spanish heritage. The multiracial pueblo that was formed on the banks of the Los Angeles River in the late eighteenth century played an important role in the Spanish Empire’s northward expansion into “Alta California,” yet that role was obscured by early Anglo-American historians who made unsubstantiated charges of the laziness, ignorance and uselessness of the original inhabitants.1 These oversights and misrepresentations tended to overshadow the remarkable accomplishments of the society that developed on the western frontiers of the Spanish Empire. This multiracial society proved crucial to Spain’s colonial expansion into North America and set the stage for the modern development of the Los Angeles area.2

When El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de Los Angeles Del Río de Porciúncula (The Town of Our Lady the Queen of the Angels on the River Porciúncula) was established in 1781, the majority of the pobladores (settlers) had African ancestry. The presence of these earliest blacks was the result of Spain’s eighteenth-century expansion of its empire northward into what was then known as Alta California. The original settlers of Los Angeles came from areas that are now states in western Mexico, a region where the Spanish empire relied heavily on African and mulatto3 populations as soldiers (black militiamen), and laborers in agriculture and mining. As a result, racial restrictions on upward social mobility of those with African heritage were more relaxed than in other parts of the empire. The shortage of Spaniards willing to serve on the Western frontera (frontier), led to the development of a substantial free black population living in the Pacific coastal areas of Sinaloa, Sonora, and Baja California. Estimates have placed Africans and mulattoes at greater than 25 percent of the overall population living in these regions during the eighteenth century.4

Despite Spain’s rigid racial classification system that placed Africans (negros) and Indians (indios) at the bottom, Africans and mixed-race individuals enjoyed greater social mobility on the Western frontier.5 Racial mixing was more common in California than in Anglo-dominated portions of North America, with men of all races tending to marry indigenous women (indias) or African/European/indigenous women of various mixtures (mulatas and mestizas). Spanish men also held African and Native American concubines. As a result, mulattoes and mestizos quickly outnumbered other groups, and many of the original African Californios exhibited gradual “browning” over time as people married into other ethnic groups.6 By 1760 one Spanish observer noted that most of the soldiers on Spain’s Western frontier were mulatto.7 Africans and Indians who became Christians were considered part of the “gente de razon” or “people of reason,” thus elevating their social standing.

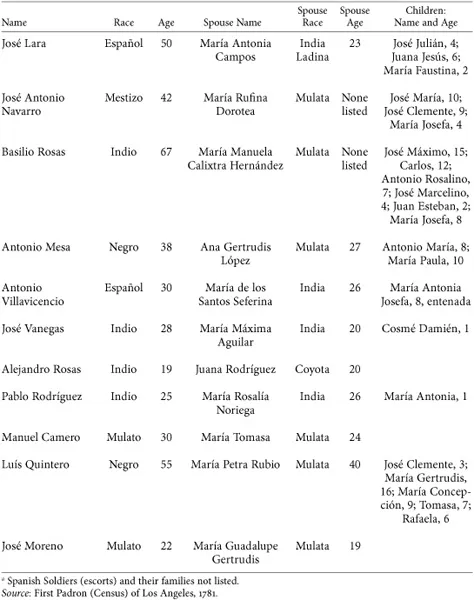

When Spanish imperial authorities decided to head off the encroachment of Russians and English on the northern Pacific Coast by establishing a network of missions (clergy settlements), presidios (army forts), and pueblos (villages) in Alta California, many of the people recruited as settlers were free Africans or mulattoes from Baja, Sinaloa, and Sonora.8 Of the original forty-six pobladores, at least twenty-six of them were at least part African (see table 1.1).

TABLE 1.1

Original Pobladores at Los Angeles, 1781a

The early pueblo at Los Angeles was not isolated from nearby missions and presidios. Several of the Spanish soldiers who escorted the eleven pobladores families also lived in the settlement with their own families, and there was considerable exchange and movement back and forth between the pueblo at Los Angeles, the mission at San Gabriel (roughly ten miles away) and the presidios at Santa Barbara and San Diego (each about one hundred miles away). The pueblo also received regular supplies from other parts of New Spain that arrived by ship near San Pedro and were brought overland to Los Angeles. The lifestyles of pueblo residents were strictly controlled by the military, local government authorities, and the Catholic Church. Each poblador had to be registered to live in a settlement, and could not travel away from the pueblo without the permission of local authorities. The job of the pobladores was to grow crops and raise livestock to help provision the soldiers at Santa Barbara. In exchange, they were provided with the supplies and materials necessary for survival until they could become self-sufficient. There were strict guidelines governing conduct in each pueblo and restricting relations with local Indian tribes.9

Unlike in many other parts of the Spanish Empire, there was little social distance between poblador families. Mulattoes, Spaniards, mestizos, and indios (except the local Indians) tended to intermingle and marry with little restriction in colonial Los Angeles. Spanish military officers and their families were the closest to an isolated aristocratic class because the Spanish system imposed ceilings on how high persons of non-Spanish ancestry could rise in the military. However, all evidence supports the likelihood that, socially, even officers tended to intermingle freely with the enlisted and with the pobladores.10 More evidence of the upward mobility of blacks in the early Los Angeles pueblo is found in the election of a mulatto, Francisco Reyes, as the alcalde (mayor) in 1793. The population of the pueblo by then had grown to 148 persons, including 59 Spaniards, 57 mulattoes, 17 mestizos, and 15 indios. However, even within the different ethnic groups then established at the pueblo, there was continued distinction made between the more Hispanicized indios and the local Native Americans, who continued to be forbidden from establishing residence in the pueblo.

By 1800 the success of the pueblo—then boasting 315 persons—had become fully apparent. The original settlement of mostly African ancestry from New Spain’s Pacific Frontier had morphed into a successful and productive pueblo and become a great asset to Spain.11 The pueblo at Los Angeles was the largest Spanish settlement in Alta California in 1807. The settlement experienced a continual influx of retired soldiers and their families from the nearby presidios of San Diego and Santa Barbara, and the descendants of the original pobladores continued to proliferate. As the population grew so did commerce, and soon foreign ships regularly visited the nearby ports.12 Although forbidden to trade with these ships under Spanish law, the trading opportunities offered by these “Yankee Clippers” were too great for Californios (including some Angelenos) to pass up, and a brisk local trade in sea otter furs developed. Because of its lucrative nature, local authorities in California routinely overlooked this trade.13 The early 1800s thus began an irreversible trend of contact with the young American nation that would eventually transform Los Angeles from its Spanish roots. During the struggle for Mexican independence from Spain that embroiled central Mexico between 1811 and 1821, foreign trade grew rapidly. Supply ships from New Spain dwindled during this time, increasing Angelenos’ reliance on trade with foreign nations.

In 1822 Californios were informed that the Treaty of Cordoba had been signed and that they now lived in a province of the new nation of Mexico. Many Californios, especially the Catholic padres who closely identified with Spain, were displeased, but there was little they could do about it.14 The political transition from Spanish colony to independent nation of Mexico did not drastically change the daily lives of the Spanish-speaking Afro-Californians, but if anything, the egalitarian ideals and prohibition against slavery introduced by Mexico’s new government likely bolstered many of the colonists’ feelings of self-esteem and their social standing. In fact, the Mexican period was a time when Africans and their descendents held some of the most important positions in California society.

Although the period of Mexican control in Alta California lasted only about twenty-five years, at least two of the Mexican governors, Manuel Victoria (1831-32), and Pio Pico (1832, 1845-46), had African ancestry. Manuel Victoria was reported by Mexican writers of the period to be a full blooded Negro,15 and Pio Pico was the grandson of one of the early mulatta residents of the Los Angeles pueblo, and indeed Pio Pico’s appearance reflected his African ancestry.

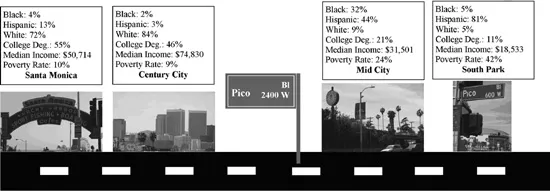

Pico—after whom today’s Pico Boulevard is named (see fig 1.1)—is the most famous of the early Afro-Mexican residents of Los Angeles, and his success in civic and commercial life is remarkable. In 1821 Pico opened a dram shop (a bar serving alcohol) in Los Angeles. He earned substantial income from his bar, along with profits from his other enterprise, a nearby hide-tanning shop. In the years that followed, Pico and his brother, Andres Pico, grew to be important figures in Mexican California and played significant roles in the transition from Mexico to the United States in 1846. During the Mexican American War, Governor Pico fled to Baja California, where he unsuccessfully lobbied the Mexican congress to send troops on behalf of the Californios. After the war, Pio Pico returned to Los Angeles and built the famous Pico House Hotel, a structure that still stood in the early 2000s near the site of the original pueblo in downtown Los Angeles.

Figure l.1. A Trip Down Pico Boulevard: From the Pacific to Downtown. From left to right, the data refer to the following geographical areas: Santa Monica City and zip codes 90067, 90019, 90015. Source: U.S. Census Bureau. Note: Statistics from the 2000 Census.

The example of Pico illustrates how blacks were hardly limited by race in Alta California, where a multiracial society developed that was open to upward mobility and assimilation of people of African descent. Particularly in civic and commercial life, Africans and their descendents experienced few limitations on their prosperity. Certainly social prejudice existed, with dark-skinned settlers more likely than their lighter-skinned counterparts to experience personal discrimination because of their appearance, but that discrimination did not significantly retard their social and economic mobility.

With the coming of American settlers, the situation changed drastically. Because of their experiences under Spanish and Mexican rule, and the ease of their previous assimilation into mainstream life, black Angelenos of the period did not have a strong racial consciousness, most considering themselves as simply “Mexicans.” For those Mexicans who retained their African features, the American period would change the way they were treated, and they would begin to suffer increasing institutional injustice alongside English-speaking blacks.

An early example of this change in racial climate is found in the reminiscences of Major Horace Bell, an early American resident of Los Angeles and an important figure in California Democratic politics of the period. Bell told the story of how during the 1853 elections, one of his aides, a Southerner, reported trouble at a polling place in the County of Los Angeles. The aide stated that a black man was attempting to vote, and that he wanted to use violence against the man. When Bell investigated, it turned out that the black man in question spoke only Spanish and considered himself to be a Mexican. The man told an interpreter that he had always voted and wanted to continue to vote under American rule. Upon finding out the man intended to vote for the Democratic candidate, Major Bell decided in favor of political expediency and sent his irate Southern aide to another polling place, thus permitting the black man to vote.16

Rise of a New Racial Order

The first English-speaking blacks arrived in the Los Angeles area some time during the early 1800s. Those who arrived by ship had made an arduous and dangerous passage around the tip of South America, or else had endured an overland journey through the Isthmus of Panama. Many others arrived on foot, by horse, or in wagons and coaches from the East.17 The earliest English-speaking black Californians were an eclectic group engaging in everything from hunting and...