![]()

[ 1 ]

Citizens in Uniform

We are all conscripts.

—Christabel Pankhurst, interview in The Egoist

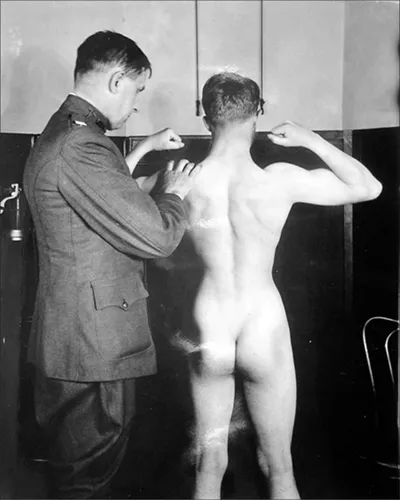

On a cold November day in 1914, Edward Casey interrupted his walk along the Barking Road in East London to enter the army recruiting office. Born of Irish parents and living in the slums of Britain’s capital, sixteen-year-old Casey thought of war service as a novelty that would enliven his dreary life. Casey lied about his age to get past the first hurdle, then went for the medical inspection with “posh-looking men” in white coats who asked him,

“Have you ever had measles, scarlet fever, sore throats?” and [a] lot of other names I had never heard of. I said “no” to all the questions. Requesting that I lay on a leather couch, he put a long thing in his ears, and with a long rubber tube with a thing on the end, tested my chest, back and belly, tapping with his fingers. “Take deep breaths” examining my eyes, nose, ears, throat, and telling me to “stand up and bend over.” [I heard him] saying: “I want to look up your rear.” It was very embarrassing having somebody you don’t know looking at, and sticking his finger up, my bum. Then he took hold of my balls, mumbling something. . . . Patting me on the shoulder, he said, “You have passed the exam.”

After this somewhat harrowing and confusing medical, Casey was sent to take an oath of allegiance, assigned to the Royal Dublin Fusiliers (infantry), and told to report at Euston Station in two days’ time. Casey, a skinny teenager with no real job or purpose in life that November morning, was now a soldier in the British army bound for active service.1

A prospective citizen-soldier undergoes his medical examination. U.S. Signal Corps, National Archives and Records Administration.

Like Edward Casey, most of those enlisting or conscripted into service for the state as soldiers, volunteers, or war workers knew little of military life or rules. They were civilians in uniform, called to serve their nations either through government conscription or through a sense of patriotic responsibility. These civilians had to be taught war and its rules, and this education extended not just to the raw recruit in the army or navy but to the entire populace of nations at war. Civilians were called to service in a variety of ways, and their service was reinforced through state legislation and funding, propaganda, and community mores. Success in war depended upon a nation’s ability to make all citizens willing conscripts for war service, either through a government-sponsored draft or through emotional or financial pressure to volunteer.2 While some civilians required coercion to offer their services to the state, others essentially “self-mobilized” in 1914 out of a sense of moral, political, or cultural obligation.3

What emerged in World War I was a complicated continuum, with trained professional soldiers at one end and civilians far from the battle lines at the other end. All along this trajectory were people who fell somewhere between these extremes—citizen-soldiers eager to retain their civilian identities, prisoners of war in a state of limbo between civil and military life, civilians militarized by foreign occupation or total war. In short, the First World War made it difficult to distinguish between soldiers and civilians, between home and front, between military and civil. Nations at war called on all citizens, whether male or female, to serve the wartime state. As British suffragette Christabel Pankhurst proclaimed, “Everything which militates against the British Empire becoming a military camp until victory is assured is treason. . . . We are all conscripts.”4 This chapter explores the ways in which civilians were conscripted by the wartime states as soldiers, but also as support staff for a massive mobilization of resources. Victory in war necessitated the transformation of nations into military camps.

The Civil-Military Divide

Although the nineteenth century had brought major changes in the waging of war, the meaning of state conscription, and the notion of “civilians,” it was not until the First World War that many of these ideas were tested under fire on a sustained and large-scale basis. Prior to the late eighteenth century, states had compelled men to join armed forces, but usually through occasional drafts that were far from universal or fair. For example, in Prussia, the eighteenth-century “canton” (regional) system recruited soldiers mostly from rural areas through a quota system, while in Britain recruiting drives often used coercion to target the poor and dispossessed.5 European fighting men lived lives of violence and brutality, and common soldiers were marginalized in civil societies. Perhaps the fact that eighteenth-century armies featured more foreign-born mercenaries than “citizens” helped set armies apart from the noncombatants they encountered.6 Most importantly, many army conscripts or volunteers in the 1700s served at least five years, and often much longer; in Russia, soldier conscripts served twenty-five years, and in Britain, their service terms averaged twenty-one years.7 The use of mercenaries and long enlistment periods contributed to the creation of armies that had a wide range of ages, experience levels, languages, and nationalities in their camps.

This older system of military life began to transform in the late 1700s. The notion of universal military service for men—citizen armies—was largely a creation of the French Revolution with its insistence on active citizenship in the nation through the 1793 levée en masse (mass draft) and Conscription Law. The revolutionary government called up all unmarried men aged eighteen to twenty-five “without exception or substitution,” which led to an army of almost 750,000 men by late 1794.8 This mass draft of male citizens was predicated on the idea that nationalism required active participation from its people, not only in the form of political engagement but also in the form of national defense. France’s revolutionary army, so the reasoning went, would fight harder and more passionately because it was composed of citizens fighting for an ideal, the nation. Putting the whole nation in arms meant also militarizing the so-called passive citizens as well, leading to the involvement of women, children, and the elderly in defense of the nation through logistical and economic support. This mobilization of all citizenry raised the stakes for France’s opponents and led inexorably to the 1793 blockade of France, which treated the whole French populace as “a besieged town.”9 From this moment on, the civil-military divide was less clear in European wars.

The French mobilization of its nation under revolutionary leaders and during the Napoleonic period also transformed military conscription in Europe over the course of the century that followed.10 Ordinary civilians rose to resist occupation and the presence of troops on their home turf, especially after brutal pillaging, physical harm, and requisition of basic necessities.11 To fight the French, popular resistance movements arose in various parts of Europe, most notably in Spain and the German regions, which constituted another kind of citizen-soldiery—guerillas. These two forms of the “people in arms”—conscripted soldiers of the state and guerilla fighters—led to a broader vision of the possibilities in arming and mobilizing the masses for defense of nations and ideas.12 The rise of popular revolutionary waves in the first half of the nineteenth century helped solidify these changes as citizens joined barricades to defend their nations.

With such ideas percolating throughout Europe early in the 1800s, Prussia passed a comprehensive conscription law in 1814, which institutionalized a draft for all men born in the nation and a permanent standing army composed of citizens. By the late nineteenth century, other European nations such as France, Romania, Italy, and Russia also began eliminating mercenaries from their ranks and creating peacetime conscription systems.13 Armies of conscripts reshaped the way war was waged, with the increased need for “mobilizing and motivating [the whole] population through the use of propaganda.”14 These changes meant that warfare looked different to soldiers and civilians alike by the turn of the twentieth century.

By 1914, universal male conscription for military service had become a norm in both peace and wartime situations, with Britain being the only European power relying still on a small professional army and volunteer military training. Even Britain, however, had a revived Volunteer Force (1860) and by the early twentieth century, a multitude of military “preparedness” organizations, including the Officer Training Corps (1908) and the Territorial Force (1908) for men, while women could join Voluntary Aid Detachments (1909) or the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (1907).15 These “part-time” soldiers and nurses retained their civilian lives, jobs, and perspectives, while constituting a trained reserve force. For the middle-class men and women who “joined up” for such volunteer experiences, the “novelty of camp,” the uniforms, the social life, and the prestige meant more than any practical understanding of real war preparation.16

In addition, Europe’s frequent late nineteenth-century imperial wars created a popular enthusiasm for the idea of war, particularly since these conflicts were fought far from home using mostly colonial troops.17 Colonial wars aimed at pacification of whole populations, making it difficult to know what victory looked like; battles were not discrete events with a clear beginning and ending but often protracted and violent conflicts that lasted years. The difference “between civilians and combatants . . . was a fluid concept,” and European soldiers found themselves redefining their understandings of the enemy in the face of colonial “guerilla” resistance.18 Yet, few in the metropoles experienced the imperial wars as more than stories in the newspapers, just as few of the conscripts understood the real nature of war from their mandatory service. The heroic descriptions of boys’ fiction did not align with the realities of the warfare that emerged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Benito Mussolini, a conscript in World War I and later the fascist dictator of Italy, described this realization in his diary: “A dreary war. . . . All the picturesque attributes of the old-fashioned war have disappeared.”19 For a generation raised on tales of dashing cavalry charges in the Napoleonic Wars and exotic colonial escapades, the realities of war service came as a shock in 1914.

As war preparedness and service became a reality of life for many Europeans, notions of “civilians” changed as well with the elaboration of laws of war and the first international conventions on peace, both of which sought to codify the experience and limits of war.20 While civilians were typically defined in opposition to military conscripts, military planners envisioned using civilian labor to fight a modern war and planned to some extent for protections of noncombatants during war. Polish banker and financier Ivan Bloch predicted the changes war would bring to European societies in his book The Future of War but was largely ignored by military planners as an amateur. Bloch argued in the late 1890s that the civil populations would be important in making modern war possible because “armies no longer consist of professional soldiers, but of peaceloving citizens who have no desire to expose themselves to danger.”21 Bloch cited the revolutions and colonial wars of the nineteenth century as well as conflicts such as the U.S. Civil War (1861–1865), Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), and Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871) as his evidence that a modern European war would not be short, would not feature heroic frontal assaults, and would have a high cost in both lives and funds.22

While Bloch’s work was read widely, pacifists rather than military planners seemed to find it most persuasive. Bloch was invited to attend the gathering of European powers in 1899 for the first Hague peace conference, convened by Tsar Nicholas II. In calling for a multinational peace convention, the tsar instructed his representatives to convene a meeting that would “by means of international discussion, [seek] the most effective means of ensuring to all peoples the benefits of a real and lasting peace.”23 At the Hague, diplomats sought guaranteed protections for soldiers and civilians during war, based upon the moral assumption that noncombatants were “men and women with rights . . . [who] cannot be used for some military purpose, even if it is a legitimate purpose.”24 A second convention in 1907 sought to extend and consolidate the rules agreed upon in 1899. These conventions were innovative, the first of their kind, and they constituted attempts to create “multilateral international” meetings that would “set out agreed rules of law.”25 However, as Nicoletta Gullace notes in her work, international conventions often relied on the arcane language of diplomat-speak, which did not capture the public imagination in the years prior to and during the war.26 Also, the Hague conventions failed to anticipate many of the scenarios that soldiers and civilians would face in World War I, including aerial bombing and civilian internment. Other Hague rules were vaguely worded, allowing for future loopholes in interpretation.

Perhaps most importantly, despite attempts at the Hague conventions to write “rules” for war, many military leaders discounted these meetings and their outcomes, especially because there was no enforcement mechanism in place. In Germany, for instance, military treatment of enemy civilians actually became more harsh by the end of the nineteenth century, with fewer protections in law for noncombatants. In her study of military culture in Germany, Isabel Hull found not only that German officers largely ignored international law and conventions in the prewar period but also that soldier-recruits received virtually “no instruction in the laws of war.”27 Hull argues that military planners were skeptical of international agreements, and instead inculcated in their men the notion that damages to civilians and their property were “unfortunate, but in any case necessary, expedients in wartime.”28

Even for those nations that embraced international law, the First World War almost immediately challenged many of these flimsy statutes decreed at the turn of the century and demonstrated the failures of scope in the conventions, particularly in regard to treatment of noncombatants. Understandings of “safety” in wartime changed, and World War I witnessed the birth of elaborate schemes (air raid shelters, civil defense plans, defensive structures) to shield citizens from the ravages of war, despite deliberate military tactics to target civilians through aerial bombing, blockade of food supply, and other means. Most importantly, the attempt to define a clear front...