![]()

Part I: Fantasies of Fakery

![]()

1. Ellen Craft’s Masquerade

The crisis of identification that emerged in the mid-nineteenth century United States was fundamentally driven by the anxieties of “a culture that worried that a full knowledge of a person’s racial origins could become obscured” (Otten 231). In the antebellum period these anxieties emerged in increasingly desperate attempts to codify racial difference as biological and therefore inescapable. The ability of fugitive slaves to subvert, manipulate, and defy these attempts through their successful escapes both challenged and accelerated southern white efforts to define race as physically fixed. Additionally, by midcentury the increased public role taken by women in the abolition and suffrage movements and accompanying challenges to raced and classed notions of masculinity and femininity created new fears over the “natural” roles and attributes of the sexes.1 The many historical and literary studies of these related dynamics, however, have rarely addressed the contemporaneously emerging anxiety regarding the knowability of the disabled body. Yet this too is a fundamental and inextricable element of the identificatory crisis, and figures of feigned or suspected disability began to emerge prominently to represent this deepening fear.

In one such figure, the fugitive slave and author Ellen Craft, we find all three forms of embodied social identity unmoored from physical and representational certainty, and so her story represents a touchstone for the eventual emergence of fantasies of identification surrounding disability, race, and gender. By examining a series of representations of Craft, including critical and creative responses by African American and feminist writers, we see not only the inextricability of these identities but also the crucial role played by disability in enabling flexible understandings of other supposedly biological identities.

A Complication of Complaints

In 1845 Ellen Craft and her husband, William, escaped from slavery in Georgia by traveling disguised as a “white invalid gentlemen” and his valet. After a four-day journey they arrived on free soil in Philadelphia and soon became prominent in the Boston-based abolitionist movement, telling their story to large audiences and swiftly gaining fame that eventually led to pursuit by southern agents seeking to reenslave them. The Crafts escaped once again, this time to England, where they later authored a narrative of their escape, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, published in 1860 by London’s William Tweedie.2 The Crafts’ narrative has received a significant amount of critical attention, much of which has focused on the racial and gender passing perpetrated by Ellen, while a secondary concern has been the prominence of the Crafts on the abolition circuit before the Civil War.3 However, no historian or literary critic has yet grappled with the presence of disability in the narrative; while the fact that Ellen pretended to be disabled is often mentioned in the course of other concerns, disability has not been addressed as a social identity that can be manipulated or interpreted, as can race and gender. Yet disability, and in particular the feigning of disability—what I call the “disability con”—plays an essential function in both the Crafts’ narrative and the social context in which it appeared.4

Indeed the disability con is an important element for many fugitive slave narrators, such as James Pennington, who pretended to have smallpox, and Lewis Clarke, who employed disguises very similar to those of Ellen Craft, including green spectacles and handkerchiefs tied around his forehead and chin (Pennington 565; Clarke and Clarke 139, 147). A number of historians have briefly noted the use of feigned illness and disability among slaves as a means of resistance, as well as the related cultural dynamics of suspicion and surveillance, yet this context is not generally invoked in discussions of Ellen Craft, unlike examples of gender or race-based masquerades.5 My consideration of disability in the Crafts’ narrative is not to negate other critics’ arguments but rather to enhance and complete them, particularly those that argue for the narrative’s portrayal of a mutually constitutive relationship between race, gender, and class. In these many insightful analyses of Ellen Craft’s “tripartite disguise” (Browder 121), the fourth crucial element of that disguise is rendered invisible and haunting.6

Yet a close reading of the narrative evolution of Ellen Craft’s disguise clearly demonstrates the intimate and constitutive relationship of race, gender, class, and disability. In William’s narration, he and Ellen first think of racial masquerade, suggested by Ellen’s white skin. Next they decide upon gender-crossing, due to the perceived impropriety of a white woman traveling with a black man. But the class status of the white male persona adopted then presents the new obstacle of literacy:

When the thought flashed across my wife’s mind, that it was customary for travelers to register their names in the visitors’ book at hotels, as well as in the clearance or Custom-house book at Charleston, South Carolina—it made our spirits droop within us. So, while sitting in our little room upon the verge of despair, all at once my wife raised her head, and with a smile upon her face, which was a moment before bathed in tears, said, “I think I have it!” I asked what it was. She said, “I think I can make a poultice and bind up my right hand in a sling, and with propriety ask the officers to register my name for me.” (Craft and Craft 23–24)

At this point the concept of the invalid—of passing as disabled—enters the disguise and soon becomes its central enabling device. The crucial function of disability for the disguise is emphasized by its remarkable proliferation throughout the narrative, which begins immediately after the conversation just quoted. Ellen fears that “the smoothness of her face might betray her; so she decided to make another poultice, and put it in a white handkerchief to be worn under the chin, up the cheeks, and to tie over the head” (24). Then, nervous about traveling in the “company of gentlemen,” Ellen sends William to buy “a pair of green spectacles [tinted glasses]” to hide her eyes (24). We immediately discover the efficacy of these stratagems, as William observes that, during the escape, “my wife’s being muffled in the poultices, &c., furnished a plausible excuse for avoiding general conversation” (24). At the time of the disguise’s inception, no specific illness or condition is referenced, although later in their journey, Ellen will claim to have “inflammatory rheumatism” (38).

In fact during the Crafts’ four-day journey, Ellen acquires new impairments whenever discovery is threatened: when spoken to by an acquaintance who might recognize her voice, she “feigns deafness” (Craft and Craft 29); when other passengers are inclined to become too social, she goes to bed, citing her rheumatism (30); and when two young white ladies appear overly interested in the dapper gentleman, Ellen quickly becomes faint and must lie down quietly (39). As “problems of possible recognition, of hotel registration, and of reading are all solved by more and more complete adoption of the role of invalid master” (Byerman 74), we see that the validity of Ellen’s racial, gender, and class passing hinges upon the invalidity of her body.

Yet that invalidity has been naturalized or ignored by critical readings of the Crafts’ narrative, discussed as a purely material and expedient factor rather than a social identity requiring analysis. For instance, it is only after the Crafts’ narrative has explained the elements of the invalid disguise that we reach that favorite moment of critics, the transformation of Ellen into a “most respectable-looking gentleman” through cross-dressing and a haircut (Craft and Craft 24). The transgression of this gender, race, and class masquerade is so interesting that critics and historians alike tend to disregard the fact that Ellen does not actually travel as this “respectable-looking gentleman” but as his invalid double, bandaged and poulticed and spectacled in the extreme. Clearly, passing as white, male, and even wealthy is not enough to effect the Crafts’ escape. In fact none of these acts of passing could have succeeded, apparently, without the necessary component of passing as disabled.

This complex interdependency of identities, signified in the text when William tells an inquiring traveler that his master suffers from “a complication of complaints,” presents a troubling challenge to scholars of African American history. Both abolitionists and freedmen of the Crafts’ time and African Americanist scholars and critics today appear deeply invested in the recuperation of the black body from a pathologizing and dehumanizing racism that often justified enslavement with arguments that people of African descent were inherently unable to take care of themselves—in other words, disabled.7 Thus we find throughout nineteenth- and twentieth-century narratives and scholarship an emphasis on wholeness, uprightness, good health, and independence—all representational categories that the Crafts paradoxically needed to subvert in order to attain actual freedom.8 As Jennifer James observes, “In post–Civil War African American literature particularly, it was imperative that the black body and the black ‘mind’ be portrayed as uninjured by the injuring institution of slavery in order to disprove one of the main antiblack arguments that surfaced after emancipation—that slavery had made blacks ‘unfit’ for citizenship, ‘unfit’ carrying a dual physical and psychological meaning” (15). With this awareness of the complicated and important history behind representations of disability in the African American context, it is nevertheless important to elucidate the presence of disability in the Crafts’ narrative to understand how the entwined fantasies of racial, gender, and disability identification functioned both to enable their escape and to shape its subsequent interpretations.

Lindon Barrett, for example, argues that “the central act of the Crafts’ escape is the removal of what is designated as an African American body from [a] position of meaninglessness to the condition of meaning and signification” (323). By claiming that the bodies of African Americans have been “taken as signs of nothing beyond themselves,” Barrett recasts the function of whiteness in the Crafts’ escape as providing not only literal freedom but ontological existence. In contrast, Dawn Keetley suggests that Ellen’s passing as a white man functions as “a concealment of any distinguishing features, rather than as a positive accrual of ‘white’ and ‘male’ features” (14). Thus Ellen’s disguise—or at least the descriptions of her disguise in the narrative—“highlight what she is not” (14). Both of these analyses draw upon deconstructive theory to read race as a matter of a paradoxically absent presence or present absence. This analysis relies on Derrida’s concept of the supplement, as that which is added to an apparently complete text but is actually necessary to its meaning, “the not-seen that opens and limits visibility” (163).

I suggest that not only is the supplement a useful concept for examining the function of disability in the Crafts’ narrative but that many critical analyses of the narrative also unconsciously rely upon disability as supplement. Sterling Lecater Bland, for example, discusses Ellen’s mobility and agency without referencing her invalid disguise, instead emphasizing “Ellen’s remarkable ability to challenge a series of raced, classed, and gendered associations” (Voices 148, my emphasis). Such a dynamic is also particularly noticeable in Barrett’s repeated referrals to Ellen’s bandaged hand in a paragraph ostensibly devoted to analysis of her racialized body:

Like the bandaged hand, the inscription of the white male figure on the black female body of Ellen is an essential element of the Crafts’ escape. . . . Like the bandaging of her hand, Ellen’s regendering refigures advantageously “the absence of a presence, and always already absent present” on which signification depends. . . . What is more, the transfiguring of Ellen’s body, like the bandaging of her hand, divides her body. The new status of this body within the condition of meaning necessitates that it be divisible. The bandaging of her hand and cropping of her hair redirect and redistribute the interpretive gaze aimed at her. (331, my emphasis)

The mantra-like repetition of “the bandaged hand” in this paragraph repeatedly evokes but endlessly defers the presence of disability as fundamental to Ellen’s disguise—and thus to her racial meaning. In this sense disability appears to function for Barrett, much as it functions within the narrative, as the necessary “bridge” that enables racial and gender mobility while itself remaining fixed and apparently immobile. This dynamic can also be understood through Butler’s concept of the constitutive outside, “the excluded and illegible domain that haunts the former domain as the spectre of its impossibility, the very limit to intelligibility” (Bodies that Matter xi). The pertinence of Butler’s analysis to this particular example is highlighted in her further clarification of the constitutive outside as “a domain of unthinkable, abject, unlivable bodies” (xi). The extent to which the body marked by disability is unthinkable and even frightening for contemporary critics studying the Crafts’ narrative is captured in Barbara McCaskill’s description of Ellen’s bandaged face as a “facial monstrosity” (“Yours” 520).

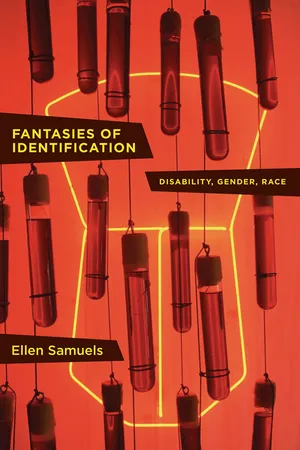

McCaskill is referring to Ellen’s “likeness,” the engraved portrait that was sold to raise money for the abolitionist cause even before the publication of the Crafts’ narrative, and which has accompanied every published edition of the narrative (Fig. 1.1). The engraving shows the head and upper body of what appears to be a smooth-faced young white gentleman with curly dark hair escaping a top hat to cover his ears. He is dressed in a black suit and stiff white collar, with a light-colored tartan plaid sash crisscrossing his front. His face is not bandaged, and the “green spectacles” used during the escape appear to have been replaced by a pair with clear lenses. The only remaining element of the invalid disguise is the white sling, which no longer supports the figure’s arm but simply hangs around his neck, slightly tucked between elbow and body. In this hanging position, parallel to the tartan sash, the sling looks like another sash or scarf, its disability function obscured to the point of invisibility.

The fact that this engraving purports to represent Ellen in her disguise yet actually represents an adapted version of the disguise with all signs of disability removed or obscured, has confounded many critics. Bland, referring to William/the narrator’s observation that “the poultice is left off in the engraving, because the likeness could not have been taken well with it on” (Craft and Craft 24), remarks, “What is unclear is whose likeness would be obscured by the poultice. Is the engraving intended to represent Ellen, William’s wife? Or is the engraving intended to show Ellen in the disguise she used to pass as a white gentleman traveling with his black slave? The engraving fully succeeds at neither, thus forcing the reader to ponder the reason for the apparent deviation” (Bland, Voices 150). While Bland does not offer an answer to this question, Ellen Weinauer concludes that the removal of the poultice suggests that “it would appear that the purpose of the engraving is to represent not ‘Mr. Johnson,’ but Ellen herself” (50). But if the purpose was to represent Ellen, why is she still dressed in her male costume? As Keetley observes, the picture does not show one “discernible race or gender,” instead portraying “a permanent state of racial and gender ambiguity” (14).

I contend that the purpose of the portrait is to represent the “most respectable-looking gentleman” so beloved of critics—that is, to represent the aspects of Ellen’s disguise that subvert nineteenth-century assumptions regarding the immutability of race and gender, while removing those aspects that even by implication show the African American body as unhealthy, dependent, and disabled. Thus McCaskill’s characterization of a couple of bandages as a “monstrosity” is clarified by her claim that “[with] her bandaged maladies a mere and known pretense, Ellen’s frontispiece portrait articulates the ...