![]()

1

Haitian Protestant Culture

“Why do you wear your hair like that? You should have hair like me!” These were the words of a pastor admonishing me while I was being threatened with physical removal from a Pentecostal church in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, in 2002.1 I had gone to Haiti to study Protestant religious culture, seeking to understand how it affected the lives of Haitian Protestant migrants. I would learn that the religious culture of Protestants in Haiti directly informs the production of symbolic boundaries by Haitian Protestant migrants in the United States and the Bahamas. As anthropologist Takeyuki Tsuda argues, a complete and comprehensive ethnography of the lives of transmigrants (people whose identities are split between two or more nation-states) requires fieldwork in both the sending country and the receiving country to understand the influence of migration on their ethnicity and to analyze the transnational linkages between the two countries that frame their experiences (Tsuda 2003, 55). Without sufficient knowledge of the premigratory religious experiences of Protestant Christians in Haiti, any analysis of the post migratory experiences in the Bahamas would be religiously decontextualized.

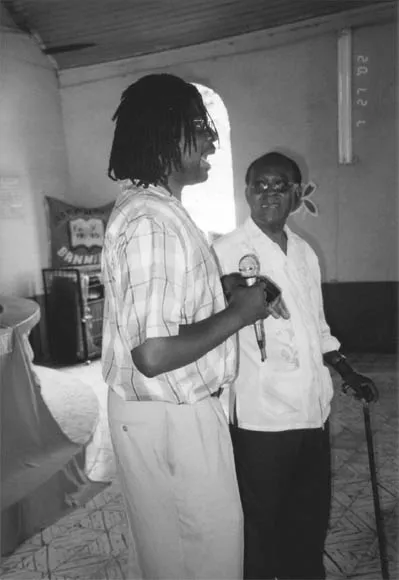

From July to August 2002 I participated in and observed church services and other Protestant practices in Port-au-Prince. During this time I wore my hair in dreadlocks, a hairstyle in which strands of hair are twisted into ropelike locks. While walking down the streets of Port-au-Prince I, a black American of Haitian descent, was referred to as a blan (white; foreigner) and “dred.” I was unfamiliar with the religious culture of Protestant churches in Haiti and did not anticipate that the way I wore my hair would be a problem. The reactions I received to wearing dreadlocks in the United States were more of a complimentary nature and it was also a common hairstyle for men and women of African descent in Saint Louis, Missouri, where I lived at that time. In fact, I was not made to feel uncomfortable at the Haitian Protestant churches I had attended previously in Kansas City and Saint Louis, Missouri, New York, and Boston, Massachusetts. So I naïvely believed that my hair and my presence, by extension, would not be an issue, let alone a spectacle, in a Protestant church in Port-au-Prince.

While in Port-au-Prince, I spent the majority of my time at the First Baptist Church of Port-au-Prince, and I recall receiving some stares from other churchgoers the first few times I attended Sunday morning services. At a later visit, an elderly churchwoman told me that it is written in the Holy Bible that men should not wear their hair long. One of my cousins, with whom I went to that church regularly, leapt to my defense and demanded to know where in the Holy Bible the biblical law admonishing men with long hair can be found. My accuser could not recall. I would later find out that the Bible verse with which the woman attempted to discipline me could be found in 1 Corinthians 1:14–15 (Ryrie Study Bible 1994, 1768), which states: “Does not the very nature of things teach you that if a man has long hair, it is a disgrace to him, but that if a woman has long hair, it is her glory?” The next time my dreadlocks became an issue was at a Pentecostal church.

Since my exposure to Protestantism in Haiti during the trip had been limited to Adventists and Baptists, I decided to attend a Pentecostal service one Sunday to broaden my perspective. My maternal aunt agreed to accompany me and we attended service at L’Église de Dieu (Church of God), Delmas in Port-au-Prince. I began filming the service without prior approval from a church official. Twenty minutes into the service a church member approached me and demanded to know who I was, why I was filming, and whether I had received authorization from the head pastor. I explained the nature of my research and we walked down to the bottom level of the church to receive authorization. The head pastor immediately interrogated me while church congregants surrounded us. He asked me: “Why do wear your hair like that? You should have hair like me! [He wore his hair in a well-kept Afro.] Are you converted? We don’t allow people like you in our church!” I apologized profusely about filming church activities without prior approval and explained that I was an anthropology doctoral student studying Protestantism in Haiti. The main reason that I was not physically removed from the church that day was the fact that I am also the grandson of Alice Jean-Louis Fougy, a renowned Haitian Baptist missionary who had preached in Haiti and throughout the Haitian diaspora for more than fifty years and who had passed away in 2001. The head pastor had known her personally, and after I informed him of my relationship to her, he agreed that it would be fine for me to continue to film the service. When I rejoined the service he made an announcement in front of his congregation of three hundred to four hundred people that I would be filming at the church that day. He added, “Please do not be shocked by his appearance.”

The author, with his father, Bertin Louis, MD, addressing the congregation at L’Église de Saint Paul, Port-au-Prince, Haiti, July 2002.

After this mortifying experience, I learned that in order to conduct research among Protestants in Haiti and elsewhere, I needed to cut off my long hair (which I did in 2004) and wear it in an appropriate manner for conducting fieldwork among Haitian adherents of Protestant Christianity. Being accosted by a church lady at one church, and being threatened with removal by a pastor from another, has taught me a great deal about Haitian Protestantism. Appearance—that is, the way Haitian Protestant Christian men and women dress, wear their hair, and present themselves in public—is one of the shared aspects of Haitian Protestant culture that provides the burgeoning transnational religious movement with some cohesion. That I was made to feel uncomfortable because of the way I wore my hair, then, is linked to the creation and maintenance of Protestant Christian religious boundaries in Haiti and the Haitian diaspora. Throughout my time in Haiti and the Bahamas, it became readily apparent that appearance in Haitian Protestantism is a reflection of karacktè (character), a fundamental and foundational trait of someone who comes from the devout Haitian Protestant Christian tradition. In the Bahamas, appearance was a key factor in the creation and maintenance of the symbolic boundaries (Kretyen, Pwotestan, and moun ki poko konvèti) that organize parts of the archipelago’s Haitian Protestant diaspora. The reactions to my appearance from Pentecostals in Haiti were similar to the reactions I observed and recorded in interviews among devout migrants in the Bahamas to seemingly less devout Protestants. These reactions reflect Protestant Christian culture in Haiti, which is the starting point for Haitian migrant religious practice in New Providence. My transnational research demonstrates that the appearance of migrants is an aspect of a larger, shared religious culture that is maintained and emphasized in the Bahamas. Another factor that gives this transnational religious movement some cohesion is the Protestant Christian rejection of Vodou.

Rejection of Vodou as a Unifying Factor

Haitian Protestantism, as scholars have noted, defines itself in relation to Vodou. When Protestantism made inroads in Haiti during François Duvalier’s dictatorship (1957–1971), many Haitians who previously had served lwa (ancestral spirits) publicly renounced them and became Protestant. As Frederick Conway (1978, 169), an American anthropologist who wrote one of the first ethnographies about Haitian Pentecostalism recognizes, “the fine theological distinctions which separate the various Protestant denominations are not particularly meaningful to Haitians. That all Protestant organizations oppose Vodou and promise protection to those who reject Vodou is more significant.” This stance against Vodou is also prevalent among Haitian Protestants in the Bahamas. When migrants in New Providence’s Protestant community were asked why so many Haitians are poor, why there were high rates of unemployment in Haiti, and why the Haitian economy is in shambles, most respondents considered an overarching spiritual factor that is at the heart of Haiti’s troubles in general and has affected their personal lives in the Bahamas as well: Vodou. Many devout Haitian Protestant migrants pinpoint the exact historical moment when Haiti’s misfortune began to the Bwa Kayiman (Bois Caïman) Vodou Congress, which, as noted earlier, occurred in the French colony of Saint-Domingue when Haitians are said to have received their freedom from European colonial powers through consecration with dyab (the Devil). A maroon who escaped from a plantation near Morne Rouge named Boukman led the Bwa Kayiman Vodou Congress, which was pivotal to the beginning of the Haitian Revolution (1791–1803). Trinidadian Marxist historian C. L. R. James (1963, 87) observed the importance of this moment in a stirring account of the ceremony, believed to have occurred in August 1791:

A tropical storm raged, with lightning and gusts of wind and heavy showers of rain. . . . [T]here Boukman gave the last instructions and, after Vodou incantations and the sucking of the blood of a stuck pig, he stimulated his followers by a prayer spoken in creole, which, like so much spoken on such occasions, has remained. “The god who created the sun which gives us light, who rouses the waves and rules the storm, though hidden in the clouds, he watches us. He sees all that the white man does. The god of the white man inspires us with crime, but our god calls upon us to do good works. Our god who is good to us orders us to revenge out wrongs. He will direct our arms and aid us. Throw away the symbol of the god of the whites who has caused us to weep, and listen to the voices of liberty, which speaks in the hearts of us all.”

Six days later, slaves of the Turpin plantation, led by Boukman, indiscriminately massacred every white man, woman, and child they could find (Simpson 1945). This event began a general insurrection that would lead to the Haitian Revolution, the only successful slave revolt in human history that extended the rights of liberty, brotherhood, and equality to black people and articulated common humanity and equality for all Haitian citizens.

Although the story of Bwa Kayiman has inspired many Haitians and other peoples of African descent who share a similar history of bondage, many Haitian Protestants today find it offensive and believe that this event was the exact historical moment when Haiti was “consecrated to the Devil.” By extension, then, Bwa Kayiman is seen to have ensured a legacy of misery in Haiti that is reflected by the underdevelopment that grips it today.

This counter-hegemonic reading of Bwa Kayiman is clearly articulated by Chavannes Jeune, a pastor and evangelist from Les Cayes, Haiti who was a candidate for the Haitian presidency in 2005. He is also the president of the Baptist Church of Southern Haiti and the founder of a group called “Haiti for the Third Century” that has as its purpose to “take Haiti back from the Devil, and dedicate her to Jesus Christ.” In an interview with the Lincoln Tribune, Pastor Chavannes stated his belief that the nation of Haiti is still in bondage primarily because “the country was dedicated by a Vodou priest [Boukman] at its liberation” and “[Haiti] has been in bondage to the Devil for four generations” (Barrick 2005).

While Haitian Protestants acknowledge that Vodou is part of Haitian culture and their rasin (roots), it is supposed to be rejected by a Protestant Christian. Dr. Charles Poisset Romain, a Haitian sociologist and the preeminent expert on Haitian Protestantism, explains that Protestantism is a religion of rupture. This rupture occurs with lemonn (the secular world) and the rejection of Vodou, a New World African religion, and is essential to being modern and to being a Christian (1986, 2004).

In interviews conducted with devout Haitian Protestant migrants in the Bahamas, I asked two questions concerning Haiti and contemporary Haitian society. The first question was “Sò panse de sitiasyon sosyal Ayiti (What do you think of Haiti’s social situation)?” and the second “Sò panse Ayiti bezwen pou chanje sitiasyon sosyal li (What do you think Haiti needs to change its current situation)?” In response to the first question, the majority of respondents born and raised in Haiti described the country’s situation in overwhelmingly negative terms.2 One Haitian Protestant male, who stayed in contact with family and friends in Haiti during the time of his interview, stated that he had heard that life in Haiti had worsened since he left for New Providence in 2002. When the second question was answered, the majority of respondents referred to God as the only solution to both alleviate Haiti’s endemic poverty and stabilize this country racked by economic, social, and political crises. Many also averred that if the country’s president was a devout Protestant Christian, the country would have a better future. Sister Maude’s reflections illuminate this common belief that the practice of Vodou is an important reason behind the crisis in Haiti.

I interviewed Sister Maude in New Providence on September 6, 2005, about her life and her views on Haitian Protestantism. At the time of our interview, she was thirty-one years old and had attended International Tabernacle of Praise Ministries for one year. She had converted to Protestantism when she was thirteen and was baptized at age seventeen. Unlike the majority of Haitians who migrate to the Bahamas from Haiti’s northern states, she was from Port-au-Prince, Haiti’s capital. Before her migration she had attended L’Église Baptiste Patriarche de Caseau, a charismatic Baptist church in Port-au-Prince where adherents receive the gifts of the Holy Spirit. In her interview, she explained that her family was deep into Vodou, and she listed different family members who served lwa.

I asked Sister Maude to describe Haiti’s socioeconomic situation at the time. She replied, “I don’t see anything for Haiti. For Haiti to change its current situation, the people have to stop committing crimes, stop the blood from running in the streets, and turn their faces toward God. Turn their faces toward God because the people, the Haitian people, have consecrated the country with the Devil.”3 When asked further about her opinion of Vodou and its effects on Haitian society, she attested:

Haitians give Vodou top place in Haitian society. . . . It’s the reason why the country is in the state it’s in, you understand what I’m saying?

Imagine a person, a small peasant who [has not enough to eat for himself] but has a goat, and is feeding it, fattening it up to give to lwa (ancestral spirits), to give lwa food every year. While this person is fattening the goat, this person has children, this person has who knows how many children they can’t send to school. And then this person has to save what they have to give lwa food. What is this person giving their food to? Some talking [incantations], something this person does [rituals associated with Vodou], and then throws the stuff on the floor? Imagine a person who goes to a sacred tree every year and then rolls around in the mud, a place that’s dirty, a place that smells like a place where a pig would roll around in. How can you make me understand [this] . . . that this is not misery that the Devil is creating in the country?

Do you understand what I’m saying? Because if you’re not a pig there’s no reason for you to be rolling around in the mud. How does someone bathe in dirty water, in mud? The person is not a pig. This is normal for a pig. . . . I think that all of our ignorance, [the ignorance of] the Haitia...