![]()

Part I

Resituating Positive Development for Urban Adolescent Girls

![]()

1

The Many Faces of Urban Girls

Features of Positive Development in Early Adolescence

Richard M. Lerner, Erin Phelps, Amy Alberts,

Yulika Forman, and Elise D. Christiansen

For much of its history, the study of individual (ontogenetic) development was framed by nomothetic models (e.g., classical stage theories) that sought to describe and explain the generic human being (Emmerich, 1968; Lerner, 2002; Overton, 2006). Within the context of these models, both individual and group differences—diversity—were of little interest, at best, or regarded as either error variance or evidence for problematic deviation from (deficits in) normative (and idealized) developmental change (Lerner, 2004a, 2004b, 2006). With European American samples typically regarded as the groups from which norms were derived—and, as well, with male samples often set as the reference group for “normality” within the European American population (e.g., Block, 1973; Broverman, Vogel, Broverman, Clarkson, & Rosenkrantz, 1972; Maccoby, 1998; Maccoby & Jacklin, 1974)—racial, ethnic, and gender variations from these nomothetic standards were regarded not just as differences (as interindividual differences in intraindividual change). They were interpreted as developmental deficits (e.g., see Lerner, 2004a).

This difference as deficit “lens” has been applied as well to youth developing within the urban centers of the United States (Taylor, 2003; Taylor, McNeil, Smith, & Taylor, in preparation). This association has occurred in part because youth from these areas are often children of color and/or they come from family backgrounds that were not ordinarily those involved in the research from which normative generalizations about developmental change were formulated (Lerner, 2004a; Spencer, 2006; Way, 1998). This characterization of urban youth as generically “in deficit”—as being “problems to be managed” (Roth & Brooks-Gunn, 2003a, 2003b) because of differences between them and “normative” samples in regard to ontogenetic characteristics associated with their race, ethnicity, gender, family, or neighborhood characteristics—is incorrect for both empirical and theoretical reasons.

Empirically, this characterization is an overgeneralization; it paints urban youth in brush strokes that are far too broad. That is, as is true of all young people, urban youth are diverse, varying in interests, abilities, involvement with their communities, aspirations, and life paths (e.g., McLoyd, Aikens, & Burton, 2006; Spencer, 2006; Taylor, 2003; Way, 1998). For instance, the opportunity advantages of high socioeconomic status (SES) available to some European American urban youth do not protect them from manifesting risk and problem behaviors stereotypically associated with low SES urban youth (Luthar & Latendresse, 2002); in turn, the low SES of some urban youth of color does not mean that these young people engage in risk/problem behaviors or do not achieve scholastically or civically to degrees comparable to higher SES urban youth (Mincy, 1994). Moreover, research in life-course sociology (e.g., Elder & Shanahan, 2006), in life-span developmental psychology (e.g., Baltes, Lindenberger, & Staudinger, 2006), and in developmental biology (Gottlieb, 2004; Gottlieb, Wahlsten, & Lickliter, 2006; Suomi, 2004) attests to the presence of intragroup (e.g., intracohort) variation that is at least as great as intergroup/intercohort differences.

Nevertheless, this within-group diversity has largely remained a hidden truth to many academics, policy makers, and even practitioners working in urban youth-development programs, who may assume that all urban youth may be characterized either as “at risk” or as already engaged in problematic or health-compromising behaviors. In addition to being empirically counterfactual, this view of urban youth sends a dispiriting message to young people, one that conveys to them that little is expected of them because their lives are inherently broken or, at best, in danger of becoming broken.

Moreover, the deficit interpretation of urban youth as invariantly deficient is problematic for theoretical reasons as well as for empirical ones. The problems that do exist among some urban youth are neither inevitable nor the sum total of the range of behaviors that do or can exist among them. Derived from developmental systems theory, a positive youth development (PYD) perspective (Theokas & Lerner, in press) stresses the plasticity of human development and regards this potential for systematic change as a ubiquitous strength of people during their adolescence. The potential for plasticity may be actualized to promote positive development among urban youth when young people are embedded in an ecology that possesses and makes available to them resources and supports that offer opportunities for sustained, positive adult-youth relations, skill-building experiences, and opportunities for participation in and leadership of valued community activities (Lerner, 2004c). Such supports exist even in those urban settings that many policy makers have abandoned as resource depleted or resource absent (e.g., Taylor, 2003; Taylor et al., in preparation).

Goals of the Present Chapter

If theory and research combine to indicate that characterizations about urban youth as invariantly in deficit, and as constituting a monolithic group, are overgeneralizations, then any view of urban youth that fails to differentiate between boys and girls is at least equally ill conceived and mistaken. As do urban youth in general, urban girls as a group may be expected to show interindividual differences and, as well, they may be expected to manifest a range of behaviors across positive and problematic developmental dimensions. Accordingly, the purpose of this chapter is to use the PYD perspective to discuss the developing characteristics of urban girls.

We illustrate our points about the diversity and strengths of urban girls by capitalizing on data from a large, national longitudinal study of youth, the 4-H Study of Positive Youth Development (Lerner et al., 2005; Jelicic, Bobek, Phelps, Lerner, & Lerner, 2006). We will draw on both quantitative and qualitative data from the second wave of this study (sixth graders) to discuss the facets of positive development of these early adolescent females and to identify some factors that may be involved in the promotion of PYD, the diminution of risk/problem behaviors, and the level of contributions that these young people make to their selves, families, and communities.

To begin this discussion it is useful to provide a brief overview of the PYD perspective. This orientation to adolescence allows us to understand why diversity is not equivalent to deficit, and why there is variation in the course of development of young women growing up in urban centers.

Features of the PYD Perspective

Beginning in the early 1990s, and burgeoning in the first half decade of the twenty-first century, a new vision and vocabulary for discussing young people have emerged. These innovations were framed by the developmental systems theories that were engaging the interest of developmental scientists (Lerner, 2002, 2006). The focus on plasticity within such theories led in turn to an interest in assessing the potential for change at diverse points across ontogeny, ones spanning from infancy through the 10th and 11th decades of life (Baltes et al., 2006). Moreover, these innovations were propelled by the increasingly more collaborative contributions of researchers focused on the second decade of life (e.g., Benson, Scales, Hamilton, & Sesma, 2006; Damon, 2004; Lerner, 2004c); practitioners in the field of youth development (e.g., Floyd & McKenna, 2003; Little, 1993; Pittman, Irby, & Ferber, 2001; Wheeler, 2003); and policy makers concerned with improving the life chances of diverse youth and their families (e.g., Cummings, 2003; Gore, 2003). These interests converged in the formulation of a set of ideas that enabled youth to be viewed as resources to be developed, and not as problems to be managed (Roth & Brooks-Gunn, 2003a, 2003b). These ideas may be discussed in regard to two key hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1. Youth-Context Alignment Promotes PYD

Based on the idea that the potential for systematic intraindividual change across life (i.e., for plasticity) represents a fundamental strength of human development, the hypothesis was generated that, if the strengths of youth are aligned with resources for healthy growth present in the key contexts of adolescent development—the home, the school, and the community—then enhancements in positive functioning at any one point in time (i.e., well-being; Bornstein, Davidson, Keyes, Moore, & the Center for Child Well-Being, 2003) may occur; in turn, the systematic promotion of positive development will occur across time (i.e., thriving; e.g., Dowling et al., 2004; Lerner, 2004a; Lerner et al., 2005).

A key subsidiary hypothesis to the notion of aligning individual strengths and contextual resources for healthy development is that there exist, across the key settings of youth development (i.e., families, schools, and communities), at least some supports for the promotion of PYD. Termed developmental assets (Benson et al., 2006), these resources constitute the social and ecological “nutrients” for the growth of healthy youth (Benson, 2003). Although there is some controversy about the nature, measurement, and impact of developmental assets (Theokas & Lerner, in press), there is broad agreement among researchers and practitioners in the youth development field that the concept of developmental assets is important for understanding what needs to be marshaled in homes, classrooms, and community-based programs to foster PYD.

In fact, a key impetus for the interest in the PYD perspective among both researchers and youth program practitioners and, thus, a basis for the collaborations that exist among members of these two communities, is the interest that exists in ascertaining the nature of the resources for positive development that are present in youth programs, for example, in the literally hundreds of thousands of after-school programs delivered either by large, national organizations, such as 4-H, Boys and Girls Clubs, Boy and Girl Scouts, Big Brothers and Big Sisters, YMCA, or Girls, Inc., or by local organizations. There are data suggesting that, in fact, developmental assets associated with youth programs, especially those that focus on youth development (i.e., programs that adopt the ideas associated with the PYD perspective; Roth & Brooks-Gunn, 2003b), are linked to PYD. In addition, Roth and Brooks-Gunn (2003b) report that findings of evaluation research indicate that the latter programs are more likely than the former ones to be associated with the presence of key indicators of PYD.

This finding raises the question of what are in fact the indicators of PYD. Addressing this question involves the second key hypothesis of the PYD perspective.

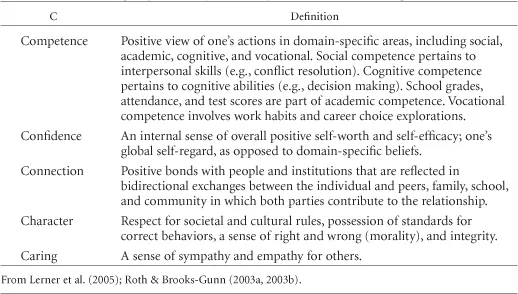

Hypothesis 2. PYD Is Composed of Five Cs

Based both on the experiences of practitioners and on reviews of the adolescent development literature (Eccles & Gootman, 2002; Lerner, 2004a; Roth & Brooks-Gunn, 2003b), “Five Cs”—Competence, Confidence, Connection, Character, and Caring—were hypothesized as a way of conceptualizing PYD (and of integrating all the separate indicators of it, such as academic achievement or self-esteem). The Five Cs were linked to the positive outcomes of youth development programs reported by Roth and Brooks-Gunn (2003b). In addition, they are prominent terms used by practitioners, adolescents involved in youth development programs, and the parents of these adolescents in describing the characteristics of a “thriving youth” (King et al., 2005).

TABLE 1.1

Working Definitions of the 5Cs of Positive Youth Development

A hypothesis subsidiary to the postulation of the Five Cs as a means to operationalize PYD is that, when a young person manifests the Cs across time (when the youth is thriving), he or she will be on a life trajectory toward an “idealized adulthood” (Csikszentmihalyi & Rathunde, 1998; Rathunde & Csikszentmihalyi, 2006). Such adulthood is theoretically held to be marked by “contribution,” often termed the “sixth C” of PYD. Contribution, within an ideal adult life, is marked by integrated and mutually reinforcing contributions to self (e.g., maintaining one’s health and one’s ability therefore to remain an active agent in one’s own development) and to family, community, and the institutions of civil society (Lerner, 2004c). An adult engaging in such integrated contributions is a person manifesting adaptive developmental regulations (Brandtstädter, 1998, 1999, 2006).

In turn, within the youth development field, longitudinal research has begun to test the idea that the development of the Five Cs, as individual indicators of a thriving youth, and/or as first-order latent constructs that are indicators of a second-order PYD construct, predict conceptual and behavioral indicators of contribution that may be indicative of development toward an idealized adulthood (e.g., see Jelicic et al., 2006). Table 1.1 presents definitions of the Five Cs that are derived from the youth development literature (e.g., Lerner et al., 2005; Roth & Brooks-Gunn, 2003a, 2003b).

A second subsidiary hypothesis to the one postulating the Five Cs is that there should be an inverse relation within and across development between indicators of PYD and behaviors indicative of risk behaviors or internalizing and externalizing problems. Here, the idea—forwarded in particular by Pittman and her colleagues (e.g., Pittman et al., 2001) in regard to applications of developmental science to policies and programs—is that the best means to prevent problems associated with adolescent behavior and development (e.g., depression, aggression, drug use and abuse, or unsafe sexual behavior) is to promote positive development.

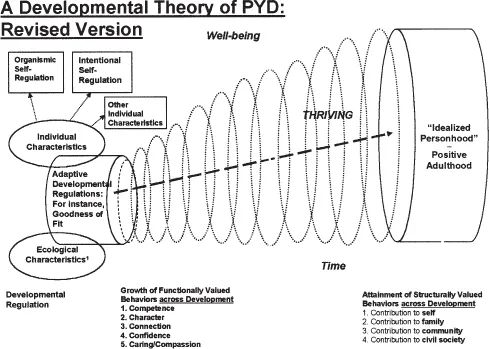

In sum, replacing the deficit view of adolescence, the PYD perspective sees all adolescents as having strengths (by virtue at least of their potential for change). The perspective suggests that increases in well-being and thriving are possible for all youth through aligning the strengths of young people with the developmental assets present in their social and physical ecology. An initial model of the development process linking mutually influential, person ←→ context relations, the development of the Five Cs (i.e., well-being, within time, and thriving across time), and the attainment in adulthood of an “idealized” status involving integrated contributions to self, family, community, and civil society was presented in Lerner (2004c) and Lerner et al. (2005). In essence, this model specified that on the basis of mutually influential relations between individual actions (involving self-regulatory behaviors) and positive growth-supporting features of the context (developmental assets), that is, through person ←→ context relations, the individual develops the cognitive, affective, and behavioral characteristics included within the PYD concept (see Table 1.1).

Further, as a result of this individual development, there emerges the “sixth C” of contribution (to the context that, in turn, supports the development of the person as an individual). The working definition of the outcome variable of Contribution is “Effecting positive changes in self, others, and community that involve both a behavioral (action) component and an ideological component (i.e., actions based on a commitment to moral and civic duty)” (see Alberts et al., 2006). In addition to the impact of PYD on Contribution, the model specifies that, as a result of the development of PYD, the individual’s development is marked as well by the diminution of problem and risk behaviors. This model is shown in Figure 1.1.

FIGURE 1.1.

1. Human resources; physical/institutional resources; collective activity; and accessibility in families, schools, and communities (Theokas, 2005).

Although still at a preliminary stage of progress, there is growing empirical evidence that the general concepts and main and subsidiary hypotheses of the PYD perspective find empirical support. Indeed, within this chapter we offer such support in regard to the positive functioning of urban girls within the early adolescent period, that is, in sixth grade. To provide this empirical evidence, we draw on data developed within the Institute for Applied Research in Youth Development—in the 4-H Study of Positive Youth Development (Lerner et al., 2005). In...