![]()

PART I

Cruel Burdens

Earth gets the price for what Earth gives us, and the truth is that, regarding the price I have paid, I need all the esteem I have earned from you to sustain my self-esteem. I have been selling being for doing.

FREDERICK LAW OLMSTED, 1890

![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Olmsted Legend

Frederick Law Olmsted was one of those men—precious few in any age—who were “honored in their generations . . . the glory of their times.”1 Indeed, Olmsted’s tragic decline into mental illness—a decline that was coupled with and perhaps related to his growing anxiety about his stature and his worth—followed almost immediately upon a series of remarkable tributes that were bestowed upon him in 1893, tributes that indicated his unique standing among his peers.

Harvard and Yale conferred honorary degrees upon him on the same day.2 A few months prior to that, at a dinner honoring the architect D. H. Burnham, Charles Eliot Norton of Harvard said: “of all American artists, Frederick Law Olmsted . . . stands first in the production of great works which answer the needs and give expression to the life of our immense and miscellaneous democracy.” In his own speech, Burnham cited Olmsted’s “genius,” and he added that it was Olmsted who should have been honored that night, “not for his deeds of later years alone, but for what his brain has wrought and his pen has taught for half a century.”3 And it was in October of that same year (1893) that the influential Century magazine published the first full-scale appreciation of Olmsted and his work, written by Mariana Van Rensselaer, a distinguished critic of art and architecture.4 Frederick J. Kingsbury, by then a friend of some fifty years’ standing, one who had long ago recognized both Olmsted’s worth and his driving ambition, wrote: “Well, you have earned your honors and you have them and I congratulate you.”5

Ironically, the twilight Olmsted soon entered upon in his own mind was a harbinger of the eclipse of his reputation that would take place over the next half-century. There seemed little place for the pastoral tranquility revered by Olmsted and his peers in the America that the Progressive Era had ushered in—when the definition of civilization and progress included immense steel-girdered skyscrapers, asphalt highways and cement playgrounds, cubist abstraction and Art Deco restlessness. Even within the related fields of urban planning and architecture, S. B. Sutton has observed, the man who had been celebrated as the dean of American landscape architecture “subsided into near obscurity,” as the practitioners in these fields “fought to shed the burden of the historic past and fixed their attention upon the International School and other modern movements.” “The greatest irony occurred during the 1920s,” Thomas Bender adds, “when Olmsted’s son, himself a leading planner, used the overpass invented by his father to preserve the natural landscape at Central Park, to begin the obliteration of the landscape at Los Angeles.”6

As recently as twenty years ago, few people other than historians could identify Frederick Law Olmsted. Since then, however, his name has become omnipresent in discussions of cities and their public spaces. When his name comes up, it usually has something to do with a debate over one of the parks associated with him—most often Central Park. Indeed, it is in terms of park design that the most avid efforts are made to keep his name alive, and—as he had in his own lifetime—he becomes the rallying point of those who would defend what they perceive to have been Olmsted’s intent against the encroachments of political and commercial interests, as well as against the proposals of other, perhaps misguided, park aesthetes. There is even an organization called the National Association for Olmsted Parks, dedicated to sustaining Olmsted’s legacy.

The effort to preserve Olmsted’s legacy was begun by the same son who, as a planner, had already given himself over to the new age. The first volume of the work published by Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., (Rick) and Theodora Kimball is devoted to the elder Olmsted’s formative years and includes a frequently unreliable biographical sketch, composed primarily of a highly selective offering of Olmsted’s early recollections and letters.7 Until the advent of Laura Wood Roper’s massively researched and superbly written biography, this earlier “official” biography had served as the basis of later sketches by cultural and urban historians. More recently historians have made use of Roper’s work, as well as the work of other excellent Olmsted scholars: Albert Fein, Charles Capen McLaughlin, and Charles Beveridge.

But as rich and perceptive as most of these works have been, the net effect has been essentially celebratory, emphasizing the best of Olmsted and sliding past, or even omitting, that which is problematical in both the man and his work. And it is the most celebratory aspects of this collective body of work that the organized Olmstedians prefer to focus upon. Indeed, the fine biography by Elizabeth Stevenson—one which, though equally admiring, tries to some degree to come to grips with “the raging ego” within Olmsted—is seldom mentioned when works on Olmsted are discussed in Olmstedian organs.8

Some of the effects of the collective celebration of Olmsted are almost inescapable: that Olmsted’s accounts of his many public and private controversies have become the accepted versions; that many of the reports and proposals that Olmsted produced in tandem with his various partners and associates have come to be identified, simply, as Olmsted papers;9 and, finally, that the public works with which the average person is most familiar today—Central Park and the other great urban parks—have become, collectively, the “Olmsted parks.”

Some signs of backlash are naturally to be expected. One such erupted in the press when M. M. Graff, a park historian who would deflate Olmsted’s reputation as the architect of this great enterprise, assailed the Olmstedians as exploiters who have “a vested interest” in his reputation. “They run an annual Olmsted convention and they don’t want the name Olmsted sullied,” Graff stated.10 In her book about the creation of Central Park and Prospect Park, Graff deplores the fact that the publicity devoted to Olmsted’s career as a landscape architect has “overshadowed the gifted men who taught Olmsted his craft.” Such men as Vaux, Jacob Wrey Mould, Ignaz Pilat, Andrew Haswell Green, and Samuel Parsons, Jr., have thus been “denied due credit” for their “major contributions” to the creation of Central Park. Nor has Graff been content only to give these men their due credit; she has called into question Olmsted’s credentials for an important aspect of the work: “Horticulture is a profession in which no unqualified person ever hesitates to meddle. Olmsted was no exception. Central Park still suffers from the effects of his ignorance of the nature and habits of plant materials.”11

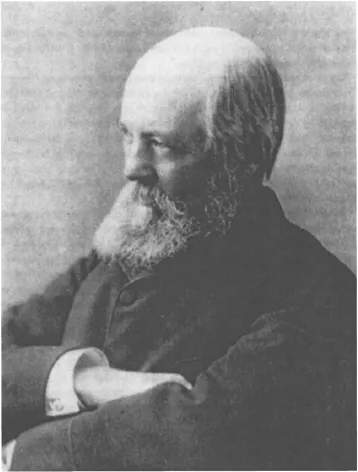

1. Frederick Law Olmsted in the final years of his career—c. late 1880s. About sixty-five here, Olmsted nevertheless remained heavily involved in his firm’s work. Now established in Brookline, Massachusetts, he was already at work on the Boston park system and would soon begin work on the Columbian Exposition and the Biltmore estate. It was in the midst of the latter work, in 1895, that Olmsted, beset by fears of failure, slipped into the mental illness that would enshroud the last eight years of his life. (National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historical Site.)

And the urban historian Jon C. Teaford was moved to complain about one writer’s “genuflecting before the achievements of Frederick Law Olmsted,” a practice Teaford found all too commonplace among “students of nineteenth-century urban planning.” Olmsted, Teaford observed, is put forth as the “authoritative teacher laying down the law,” while such notable figures as the architect Richard Morris Hunt are presented as “philistines at best and more likely dullards” for daring to challenge Olmsted’s vision, a vision that Teaford claims “has not stood the test of time.”12

But—as Richard Hofstadter has said of Lincoln—the first author of the Olmsted legend was Olmsted himself.13 Olmsted’s interrelated concerns for his own reputation and that of his profession led him to attempt numerous essays and books in his later years—the subject matter covering autobiography, various aspects of landscape architecture, the philosophy of design and the graphic arts, and so forth.14 Usually he got no further than innumerable drafts of the opening sections, or dozens of pages of notes, toward such a work. “I do my duty in writing but nobody can imagine how hard it is . . . how much it costs me to write respectably,” he told Mariana Van Rensselaer in 1887.15 At the time, he was seeking to enlist her as a propagandist for his aesthetic of landscape design, noting that it was a comfort to find what he “would like to say written by someone else.”

One of Olmsted’s concerns was to lay out an official—and rather romanticized—account of his early preparation for his profession. This he did in his embittered pamphlet of 1882, Spoils of the Park.16 According to this account, Olmsted had begun the “study of the art of parks” in his childhood, and he had read “the great works upon the art” before he was fifteen. Between his adolescence and his employment on Central Park in 1857, he states, not a year passed in which he “had not pursued the study with ardor, affection, and industry.” His two trips to Europe, he writes, were for the express purpose of studying the parks of England and the Continent, while his travels across America were devoted to the “study of natural scenery.” And he adds:

I had been three years the pupil of a topographical engineer, and had studied in what were then the best schools, and under the best masters in the country, of agricultural science and practice. I had planted with my own hands five thousand trees, and, on my own farms and in my own groves had practised for ten years every essential horticultural operation of a park. I had made management of labor in rural works a special study, and had written upon it acceptably to the public.

The Van Rensselaer article, published a decade later, presented Olmsted’s early years in far greater detail, but still held to the tenor of this “official” version of Olmsted’s youth and training—hardly a surprising fact, since the biographical aspects of the article were so heavily based upon Olmsted’s own testimony.17 Echoes of this version can be found as late as 1931, in Lewis Mumford’s appreciation of Olmsted. Mumford rhapsodized Olmsted’s preparation for his career as a “combination of wide travelling, shrewd observation, intelligent reading, and practical farming”—just as Olmsted had claimed for himself in Spoils—and Mumford called it an example of “American education at its best.”18

After Roper’s exhaustive study of Olmsted’s life and after the efforts of Roper, Fein, McLaughlin, and others to make Olmsted’s papers accessible, historians have come to see Olmsted’s career as something other than inherently disciplined or even charmingly eclectic. They have come to see it as serendipitous, if not actually haphazard.

Such a view, in fact, was one that Olmsted, near the end of his career, presented to his son, Rick, when Olmsted made use of his own early misadventures as a cautionary tale for his son. This version was set forth in one of Olmsted’s most revealing letters—written, appropriately enough, on New Year’s Day, 1895.19 This was a letter that cast a far different light on Olmsted’s earlier years than did the official version he had put forth in Spoils or had fed to Van Rensselaer for the Century article:

I was younger than you now are when my father, wishing to make me a merchant, secured me a situation in what he thought a very notable and promising place to learn the business. After trying it a year and a half, I threw it up, and with his consent . . . went to sea. Then I threw that up, and after wasting a year, wandered from farm to farm thinking that I was learning the business and so on.

At thirty, he wrote, he had finally entered the business world, as a publisher, and five years later this enterprise was bankrupt.20 It was only then that he had begun upon “the business” (landscape architecture) in which—except for the Civil War years—he worked ever since.

All that period of backing and filling between the point in which, nominally a farmer, I really acquired my profession, was a sad matter. If my father had not been comparatively (to his wants) rich, and generous and indulgent—over-much indulgent and easy-going with me—it would not have occurred. I have been successful but I should have been far more successful . . . if at your period, I would have given myself to methodological study of the profession I have since followed, or probably of any profession or calling.

Olmsted’s official version of his youth (in Spoils and elsewhere) often took liberties with objective truth—a truth that, in his anxiety over Rick’s future, he had presented here. Yet passages such as the one quoted from Spoils usually had a poetic truth about them. As noted in the introduction, Olmsted’s young manhood provides an excellent example of an Eriksonian “psychosocial moratorium”—that delay in the acceptance of adult commitments during which the young person experiments with various roles in life. Lucian Pye comments that one can see a common pattern in the lives that Erikson has studied: a pattern of the “ideological innovator . . . coming upon his life work without prior planning or design.”21 When the right opportunity presents itself, the skills such a gifted person has acquired almost by accident are fused together through his creative imagination into a work that, in retrospect, seems to have been inevitable. Van Rensselaer makes this point about Olmsted in her Century article, writing with her great good sense:

It may almost seem as if mere chance had determined that Mr. Olmsted should be an artist. But the best chance can profit no man who is not prepared to turn it into opportunity. If, at the age of thirty-four, Mr. Olmsted had not been fitted for a landscape gardener’s task, the chance which made him superintendent of the workmen in Central park could not have led him on to the designing of parks; while, on the other hand, knowing how well fitted for such tasks he was, we feel that if just this opportunity had not offered, another would somehow have presented itself.22

Olmsted’s claim that from adolescence onward he had been engaged in the constant study of parks is utter nonsense. And one may credit him with at best only a sporadically intense interest in what he called “scientific farming.” Whenever he was actually confronted with the lonely hard work this occupation entailed, however, he would develop a burning desire to be elsewhere: back in his father’s Hartford home; attending lectures at Yale, where his brother was enrolled; off on a walking tour of Europe; reporting on the South for the New York Daily Times.

That walking tour—the first of the two trips to Europe Olmsted mentions in the Spoils passage cited earlier—was clearly a classic Eriksonian Wanderschaft, a ...