![]()

1

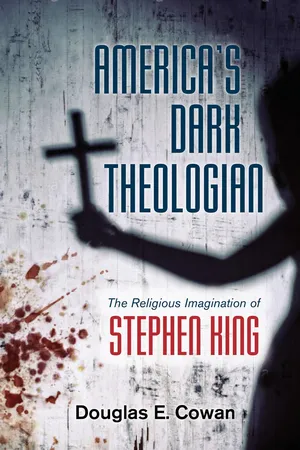

America’s Dark Theologian

Reading Stephen King Religiously

Few critical works that concentrate on Stephen King’s horror fiction contain a separate index entry for “religion,” none for “theology.”1 Tony Magistrale’s Landscape of Fear is a rare exception, but even that relegates discussion of religion to a few pages, and Magistrale, who has written more about King than other scholars, concludes that “the religious dimension in King’s work defies easy categorization.”2 This may be true, but merely pointing that out isn’t very helpful. After a few passing comments, which include an almost obligatory nod to The Stand as “perhaps King’s most religious book to date,” on the one hand, Magistrale ends up avoiding the issue, content instead to regard “the real horrors in Stephen King’s canon [as] sociopolitical in nature.”3 That is, in an analytic move that is common in pop culture critique, whatever looks like religion, or could be interpreted religiously, must mean something else. On the other hand, Magistrale suggests that the “fictional portrayal of organized religion in his books is an untempered reflection of King’s own personal beliefs.”4 In this he’s not entirely wrong, but his conclusion reflects a rather limited and parochial understanding of “religion.” When he uses concepts such as “basic Christian principles” and “true religious sentiments,” they become little more than superficial abstractions, empty placeholders in the broader conversation about religion in general and King’s work in particular.5 They suggest that religion in Stephen King is the exception, rather than the rule, and that his real questions lie elsewhere.

The reality is rather different. Indeed, religion as a social and cultural constant, and theology as a way of thinking about the nature of reality itself, are rarely absent from King’s varied storyworlds.6 Many different types of religious believers populate his stories. Some of them are bad people—Carrie’s mother, Margaret White, Under the Dome’s corrupt politician, Big Jim Rennie, or the unnamed woman in Cell, “the elderly crazy lady with a Bible and a beauty-shop perm” who attacks survivors of the Pulse as they flee Boston.7 Others, such as Desperation’s David Carver and Johnny Marinville, Under the Dome’s Piper Libby, and even The Dead Zone’s Vera Smith, who struggles to maintain her faith in the face of her son’s horrific accident, are more like the people we see around us every day. They’re just trying to get by. Simply saying that there are “religious” characters in King’s fiction, though, or that they are of a certain type doesn’t begin to plumb the depths of what these storyworlds can tell us about the nature of religious belief and the power of the religious imagination at work. Indeed, phrases such as “basic Christian principles” and “true religious sentiments” are often little more than sly ways of saying “my (correct) religion” as opposed to “your (false or hypocritical) religion.” When we oversimplify the vast and complex array of human religious beliefs and practices, “religion” often becomes “that which we clearly and unambiguously recognize as religion”—which, as Stephen Prothero points out, is often an indictment of people’s religious illiteracy, rather than a comment on the poverty of our mythic imagination.8

Often regarded as one of King’s most explicitly religious works, The Stand follows humankind’s struggle to survive in the wake of a global pandemic, the Captain Trips virus. Although this is hardly a novel scenario, in King’s hands one side in the war to reinvent society lines up behind God’s champion, embodied in the elderly Mother Abagail, the other behind Randall Flagg, who is alternately imagined as the Antichrist or the Devil himself. Magistrale calls the book an “elaborate allegory embracing the ultimate conflict between the forces of good and evil in the world.”9 While many fans do read the book as a religious allegory, they do so because King makes these allegiances explicit. We see “religion” because he tells us that that’s what we’re supposed to see, and because he provides us with clear and easily identifiable religious markers.

Indeed, although it’s written neither for Christians nor by an evangelical believer, The Stand can be read in a line of Christian apocalyptic fiction that stretches back more than a century.10 The seemingly endless Left Behind series, written by televangelist Tim LaHaye and novelist Jerry Jenkins, is merely the genre’s most recognizable entry. Since the late 1960s this kind of end-times storytelling has been buttressed by an evangelical cottage industry devoted to analyses of current events through the lens of what believers consider biblical prophecy. Rooted in nineteenth-century evangelicalism, though popularized by Hal Lindsey’s 1970 bestseller The Late Great Planet Earth, the genre has spawned myriad imitations. These are stories told by believers for believers, however, and millions of Christians read them already convinced that God has divided history into a number of distinct periods, known among the faithful as “dispensations.” Worldwide chaos heralds the last of these periods, which is marked by the rise of a charismatic, seemingly all-powerful world leader and savior, but concludes with the battle of Armageddon. In the end, as scripture foretells, God triumphs—something Christian readers both understand and expect. Certainly, The Stand can be read this way, but so what?

Mapping easily recognizable religious ideas onto King’s story may satisfy our sense of the novel’s allegorical importance, but it also blinkers us to the myriad other ways religion and theology permeate his work. Put differently, if we simply rely on the familiar, we are less likely to recognize the unfamiliar as “religious.” We are less inclined to consider the possibility that what we typically think of as “religion” might encompass only a small fraction of human interaction with the divine, or that it might have other connotations altogether. Good and evil, for example, are neither explicitly religious concepts nor the proprietary domain of religion. Yet, when we use them as ways to limit whether something is religious or not, we exclude the many other ways King prods us to question the nature of what we call “religion” and its implications for our understanding of reality. Because, with both Stephen King and the human religious imagination, it’s not about the answers we get.

It’s all about the questions we continue to ask.

Although we often treat it this way, it is not the case that something called “religion” exists as a category separate and distinct from the rest of the social and cultural world. It’s not that we know a story is “religious” simply because it contains readily available religious iconography or symbolism. There may be a priest or a church, someone may shout, “Oh God, save me!” in a moment of panic, but this kind of superficial equation is both too easy and too common.11 It ignores a much deeper truth about the stories we tell—and the stories that stick in our minds and our culture. Both the stories we have labeled “religious” and the other fictional storyworlds we create emerge from the same place in our imagination. Both are manifestations of the human search for meaning, our ongoing need to question, and our constant dissatisfaction with whatever answers we find. It’s important to remember that for many thousands of years, we have not answered our most basic existential questions with facts—because we have had so few and understood them so poorly—but with stories. Some of these, over time, have formed the basis of what we call “religion,” while others have remained simply stories.

Much of King’s horror fiction falls into the literary category that narratologists call the unnatural narrative: stories about things that couldn’t possibly happen. Narratologist Jan Alber, for example, defines stories of this type according to “the various ways in which fictional narratives deviate from ‘natural’ cognitive frames, i.e., real-world understandings of time, space, and other human beings.”12 Put differently, they are “physically impossible scenarios and events, that is, impossible by the known laws governing the physical world.”13 Yet we constantly and continually entertain these stories as though they could and do happen. We respond to them as though they are happening.

When we’re frightened by a horror story or a scary movie, we do not so much suspend our disbelief as we give in to belief in the story—both willingly and unwillingly. Drawing on cognitive and social neuroscience, literature scholar Brian Boyd points to the “emotional contagion” that is inherent in fictional narratives. Specifically, “mirror neurons fire when we perceive someone performing an action, as they would if we were performing it ourselves.”14 Often, horror culture is derided for its reliance on things that couldn’t possibly happen. Why would anyone believe such stories, critics ask, or react as though they do believe? Forgotten here, though, is that as a species we have considerable experience with unnatural narratives. What is religion, after all, but an assembled case history of believing the unbelievable? From Jonah’s three-day sojourn in the belly of a “great fish” to Muhammad’s night ride across the Middle East on a flying horse, from a boat designed to repopulate the earth in the wake of a global extinction event to several thousand people fed from a couple of fish and a few loaves of bread—as a species, we believe the unbelievable on an astonishingly regular basis.

Stories such as these do not simply spice up our varied religious narratives, they constitute the very substance of what we have come to accept as “religion.” That is, the claim that Moses met Yahweh on Mount Horeb when he encountered the burning bush, that Muhammad saw the angel Gibreel on Mount Hira, that Jonah emerged alive from the belly of the fish, or that Jesus performed miracles both authorize and certify their claims to divine authority. We believe because these stories are unbelievable, precisely because they are “violations of the ordinary.”15 As Boyd points out, “religion consists less of a coherent body of dogmas or explanatory systems than of these memorably surprising stories.”16

Yet, no matter how people construct belief in the literal truth of such events, they can never be anything other than stories. Nor does the fact that billions of people believe that they represent both historical and theological reality change or diminish their power as story. Millions regard them as meaningless fiction, hundreds of millions more as true stories. But stories nonetheless.

A Brief Walk in the Maine Woods

One problem with the reception of genre fiction, especially of an author who writes as fluidly and prodigiously as Stephen King, is that novels such as Pet Sematary or The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon can easily be read in a single evening. In the rush to find out what happens, though, we often miss what happens. We don’t slow down enough to see what’s there. As we will see, the central action in Pet Sematary is structured around the classic anthropological notion of the ritual process, and includes what we might call a mini-seminar on various religious conceptions of death and dying. The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon, on the other hand, is a straightforward child-lost-in-the-wilderness story, solidly in the tradition of fairy tales such as “Red Riding Hood,” “Snow White,” and “Hansel and Gretel.” In this short novel, however, through young Trisha McFarland’s experience in the depth of the Maine forest, King explores one of humankind’s earliest religious impulses: sympathetic magic, the belief that actions in the seen and unseen orders are connected, and a means by which hominins have for millennia controlled their fear of chaos and disruption.

Night approaches. What could be scarier than this, evoking narrative territory haunted by lean, hungry wolves, by witches in gingerbread houses, by shadows that come alive just as day departs? The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon needs little more than the simple coming of darkness to invoke the fear of being cut off from the community. Yet it is another path down which King explores our ambiguous, ambivalent relationship with the unseen order, offering another example of how deeply imbued his work is with god-talk. Like many of King’s stories, this one begins with the most mundane of circumstances: a bitter divorce, confused children who have grown hostile and resentful, a day trip to the woods intended to smooth things over, and a moment’s inattention.

With nothing more than her daypack and her little-girl grit, Trisha McFarland tries to find her way back to her mother and brother—indeed, to find her way back to anyone. Running from a swarm of wasps, she slips and falls down a rocky slope, tearing her clothes, bloodying her arm, and destroying her Gameboy. Even her blue rain poncho, which wasn’t much to begin with, is now “torn and flapping in a way she would have considered comic under other circumstances.”17 As she sits by a small stream, assessing the damage, she has only one clear thought: Don’t let me be truly alone. “Please, God,” she said into the tiny dark space behind her eyelids, “don’t let my Walkman be broken.”18 The Walkman’s radio is her only link to the world beyond the forest. Without even its small voice in her earbuds she is truly, desperately alone. She presses the power button and the radio comes to life, the local Castle Rock station broadcasting an alert about a nine-year-old girl “missing and presumably lost in the woods west of TR-90 and the town of Motton.”19

Foxhole prayers and desperate appeals to a dimly remembered deity are far more common than no...