CHAPTER

1

The Basics of the

Recovery Process

“Red: any of a group of colors that may vary in lightness and

saturation and whose hue resembles that of blood.”

—The American Heritage Dictionary

Projects do not self-destruct—they need help. The people on and around the project provide that assistance. Neither do projects get into trouble overnight. It takes time, and usually the failure starts shortly after someone thinks, “It would really be cool if we could . . .” From that point forward, the project’s future is destined for success or failure. In other words, a project’s fate is sealed from the time of its first concept, long before it is actually considered a project.

Rather than the dreams or required innovation they are based on, projects fail because of the way they are managed. For example, projects that develop highly innovative products need a structure to accommodate unknowns, rapid change in the concept, and all the other challenges of new product development. Projects based on mundane repetitive activities need the rigor of a process and the awareness that, despite superficial appearances, no project is simple. Both complex and simple projects—and all those in between—need a proper foundation. Without one, any project will end up red.

As with all effective communication, the first step is a mutual understanding of common goals. Unless you define such basic terms as success and failure, a red project cannot be saved. It is even a good idea to define the term project, whose meaning varies depending on the user’s point of reference.

The Context of a Project

The Project Management Institute’s (PMI®) and the UK’s Office of Government Commerce’s (OGC) definitions of a project are equivalent. These important definitions are referenced throughout this book.

PMI’s® A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, Fourth Edition (PMBOK® Guide), defines a project as

“a temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result.”1

According to OGC’s PRINCE2™, a project is

“a temporary organization that is created for the purpose of delivering one or more business products according to an agreed Business Case.”2

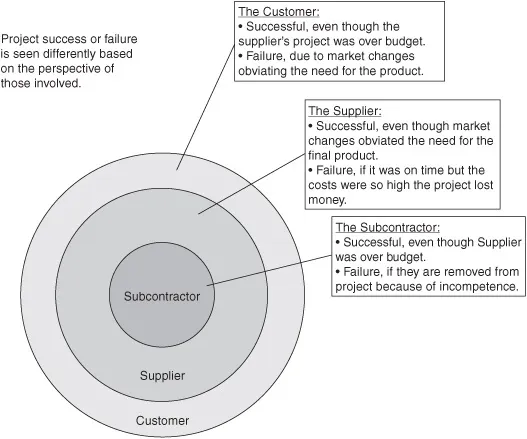

Even if we accept these definitions, the term project is relative based on the charters of the groups participating in an endeavor. All projects are actually two projects—the customer’s and the supplier’s. And, depending on the structure required to build the product, there may be numerous other project perspectives; for example, a subcontractor selected to work on some part of the project. Figure 1-1 illustrates the varying perspectives that are possible for a project.

The criteria used to define project’s success or failure is derived from the perspectives of the various participants. The customer and the supplier teams may all work for the same company, but each group has specific responsibilities and goals. One team cannot realistically be expected to fulfill the responsibilities of another team that did not meet its goals, except when the failure of one team causes failure in the other. In such a case, there must be substantial support if the rescue effort is to be successful, as well as significant reward (value) for the rescuing team.

From the customer’s perspective, the project is successful when it meets its delivery, budget, and value goals, regardless of the supplier’s trials and tribulations. On the other hand, if, say, the customer specifies the product incorrectly or misidentifies the desired market, the project is a failure.

From the supplier’s perspective, regardless of the project team’s overall performance, a project is a failure if it is significantly over budget. However, a customer’s product marketing failure does not translate into failure for the supplier. As shown in Figure 1-1, a subcontractor has its own perspectives on a project. Therefore, each team’s point of view sets the relative definition of success, failure, red, and other terms.

Figure 1-1: Perspectives on a Project

Understanding Project Success

The definition of project success is:

• The project delivers value to all parties in the project.

• The project maintains the scope, schedule, and cost established by the original definition, as well as any before-the-fact change orders.

Delivering value to all parties means that both the customer and supplier get what they need; the project’s original definition is irrelevant in determining whether this has happened. For instance, it makes no sense to deliver the original design if it fails to meet the customer’s needs. The definition of product value changes in tandem with overall business conditions; the project must adapt to those changes in a proactive manner. The frequency of change is an unreasonable gauge for judging whether a project is in trouble; improperly managed change always threatens the success of a project.

As for the second point, the scope, timeline, and budget that evolve over the course of a project may differ greatly from the original definitions, leaving the customer feeling that the project is less than successful. However, if the project managers manage change (identifying and initiating changes proactively) and the supplier delivers on its promises, the project is successful from the supplier’s standpoint. The customer, as opposed to the supplier, must be held accountable for the poor planning and inadequate assessment of its needs. The project is fulfilling the customer’s business needs; its subject matter experts must define the goal.

The supplier does own a small part of the responsibility in such a case. Generally, the supplier should be able to detect a drift in requirements, identify changes that are inappropriate, and point out ill-advised changes to the customer.

If the supplier’s project manager lets the scope of a project wander uncontrolled, fails to call discrepancies to the customer’s attention, makes promises he or she is incapable of delivering, or fails to highlight a risk that could jeopardize the project, then the effects of these actions can make the supplier’s project red.

CASE STUDY 1-1: DEFINING SUCCESS

A project that was delivering vehicle sales software to thousands of internal and franchised sales units across North America had just suffered a massive failure as a result of two problems. First, the product had a number of bugs; second, the remote install feature had failed, thereby disabling hundreds of remote users’ sales tools. Calls for assistance swamped the help desk, and it was taking weeks to mail CDs and assist novice computer users in manually installing the product. The team was under extreme pressure to release a bug fix.

The bug fixes were going to be distributed over the Internet. They required using the same tools that failed in the prior deployment, but hopefully all the issues had been resolved. When the team, severely demoralized and nervous, asked how to measure the success of the deployment, I responded with the following criteria:

• Rapid and professional handling of anticipated issues.

• Identification of all risk in the deployment.

• Having working mitigation plans for potential problems.

The deployment was successful, exercising only a few mitigation plans, all of which worked. In other words, the problems were anticipated and properly mitigated.

What Is a Red Project?

The designation of a project as red derives from the commonly used green-yellow-red color system. The organization defines a set of project attributes that are monitored (say scope, budget, schedule, quality, and resources) and assigns a formula to indicate the degree of control. Next, the appropriate color designation thresholds are defined: green, for okay; yellow when the project has minor issues; and red for a project that is in trouble. For instance, management might decide that if the period-to-date actual cost is less than 10 percent different from its projected value, then the budget is green; everything is okay. However, if the actual is between 10 and 15 percent off, it is considered yellow. More than 15 percent off, it is red. Additional shop-defined conditions may further state that if two or more monitored factors are red (say, time and resources), then the project is red.

In other words, a project is red when unanticipated and uncontrolled actions cause senior management to determine that it is performing insufficiently, based on agreed parameters. Being red is a subjective quality of a project, an unanticipated variance from the project’s current definition based on each organization’s rules. As discussed, the project’s perspective constrains the extent to which this designation will affect each participating group. The supplier’s portion of the project can be red, while the customer’s project is under control, or vice versa. From the supplier’s point of view, as long as the agreed-on parameters are met, a project is not red.

What Is Project Failure?

A project is a failure when its product is unsuccessful in providing value to all the parties. From the customer’s standpoint, the product the project is building provides the value; from the supplier’s side, it is most likely the revenue. If a project is supposed to deliver on a certain date, no sooner and no later, finishing early will have as negative a result as being late. To ignore an issue and let it continue unabated will result in failure.

As long as change requests account for any changes in schedule and budget, the ability to accept numerous requests, even if they significantly alter the project’s scope, indicates a healthy change management process. Numerous changes may, however, be a death knell for the customer’s project. Too many changes will drive up costs and delay the project, even if these attributes were incorrect from the beginning.

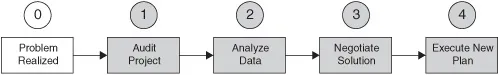

What Is Project Recovery?

When a project has been recovered, new plans and processes have addressed the issues that caused its red status. The project has been through a corrective action process; its current parameters fall within newly planned limits, and all parties (customer and suppliers) are amenable to the project’s proposed outcome. The scope may be different, the timeline may be elongated, or the project may even be canceled.

Canceling a project may seem like a failure, but for a project to be successful, it must provide value to all parties. The best value is to minimize the project’s overall negative impact on all parties in terms of both time and money. If the only option is to proceed with a scaled-down project, one that delivers late, or one that costs significantly more, the result may be worse than canceling the project. It may be more prudent to invest the time and resources on...