This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

El Salvador in Transition

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Baloyra argues that the deepening American involvement in what is basically a domestic conflict between Salvadorans has failed to eliminate the obstructionism and violence of the Originally published in 1982. A UNC Press Enduring Edition -- UNC Press Enduring Editions use the latest in digital technology to make available again books from our distinguished backlist that were previously out of print. These editions are published unaltered from the original, and are presented in affordable paperback formats, bringing readers both historical and cultural value.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access El Salvador in Transition by Enrique A. Baloyra in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Storia dell'America Latina e dei Caraibi. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

StoriaPart One

Salvadoran Reality

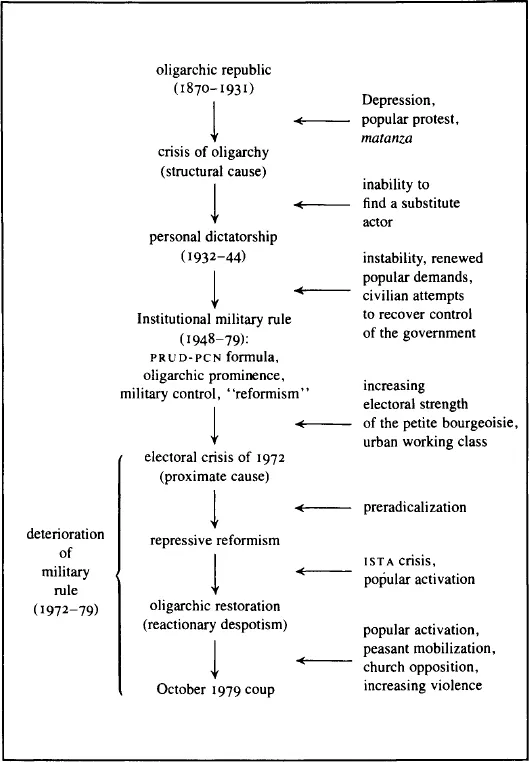

On 15 October 1979 a progressive faction of the military overthrew the government of General Carlos Humberto Romero, ending an experiment in institutionalized military rule that had lasted over thirty years and plunging the country into a political crisis from which it has yet to emerge. To locate the origins of this crisis, however, one must go much further back in Salvadoran history. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries El Salvador was an oligarchic republic, sustained by a system of export agriculture. The prime beneficiaries of this system were a group of wealthy coffee planters, who dominated Salvadoran politics and monopolized key sectors of the economy. This coffee oligarchy was unable to spare its republic from the ravages of the Depression. A peasant uprising in 1932, which was bloodily put down by the armed forces in the matanza, made it evident that the oligarchy was no longer able to manage the system by itself.

There followed a period of personalistic rule (1932–44). General Maximiliano Hernández Martínez introduced some changes during this period to make the operation of the economy somewhat more orderly and to extend the power of the state to some areas that had been the domain of the oligarchy, but the crises of 1944 and 1948 finally led to institutional military rule. Under this arrangement, formalized in the Constitution of 1950, the military tried to evolve a political formula patterned after the Mexican model of one-party domination. There were important differences between Mexico and El Salvador, however, and in addition the military made some crucial mistakes which enabled the oligarchy to continue to play a very influential role in Salvadoran affairs. The oligarchy’s opposition and the military’s indecision doomed all attempts to change the basic features of the system of export agriculture and authoritarian politics.

Between 1932 and the late 1960s the military and its allies in the oligarchy were able to defuse the more serious political crises and defeat their adversaries with relative ease. Each time a military ruler was overthrown and there was even a distant possibility of democratization, the oligarchy and the more conservative military officers were able to revive their formula of political domination and restore the system to its usual mode of operation.

The taproot of the present Salvadoran crisis must be sought in what was required to maintain this system of military rule and oligarchic economic control. In order to remain competitive, maximize its profits, and survive periods of low export prices, the Salvadoran oligarchy relied on low agricultural wages. In addition, it remained adamantly opposed to any attempt to change a very unequal system of land tenure, which enabled it to monopolize the profits of the export trade and to use these to control the financial sector as well. Therefore, military reformism could not include agrarian reform or the unionization of agricultural workers.

Military rule was legitimized through elections that, as long as the opposition remained disorganized and divided, were relatively honest. Yet therconservative militarye can be very little doubt that this system was exclusionary, not pluralist, and that it could not really accommodate effective political opposition. Beginning in the late 1960s, the opposition, now much better organized, made some inroads into the legislature, and gained control of the government of some municipalities. Opposition coalitions won the general elections of 1972 and 1977, and the military perpetrated massive frauds to remain in power and used repressive measures to quell the protests that followed.

The suppression of moderate parties advocating incremental reforms through electoral means brought about a radicalization of the opposition and an increased polarization of the political process. To counter this, President Arturo Molina tried to implement a modest program of agrarian reform during !975-76, which he hoped would ease tensions and increase the legitimacy of his government. The oligarchy resisted this so ferociously and effectively that Molina was not only defeated in the initiative but rendered unable to select his successor. Following the fraud of 1977, President Carlos Humberto Romero took the opposite tack, unleashing the security forces and paramilitary assassination squads on his increasingly mobilized opposition. Romero’s public order law and the excesses of his government attracted a lot of international attention. Guerrilla groups and popular organizations emerged as the principal opposition to Romero. Relations with the United States deteriorated considerably.

This was the scene when the more progressive element of the military moved to overthrow Romero in October 1979. While short-term factors played an important role in the deterioration and breakdown of Romero’s government, historical antecedents, serious structural imbalances, and substantial unresolved questions loomed large in Romero’s inability to restore order. The consequence of all this was a crisis which, one has to conclude, the Salvadorans brought upon themselves. The oligarchy, for its obstructionism, and the military, for its unwillingness or inability to challenge the oligarchy, must share major responsibility for bringing about that crisis.

The Salvadoran Crisis in Historical Perspective

Chapter 1

Historical Roots

Consolidating the National Government

The beginnings of export agriculture and oligarchical domination in El Salvador can be traced back to the 1850s. At that time, the government was becoming increasingly concerned about the consequences of the country’s reliance upon a single cash crop, indigo. The efforts to diversify, however, resulted instead in the monocultivation of coffee and the concentration of capital in only one sector of the economy. Rather than diversify the country’s agriculture, the government succeeded only in substituting one agricultural product for another, and this substitution had far-reaching consequences.

The expansion of coffee growing radically altered patterns of land utilization and the political economy of El Salvador. The exploitation of indigo had been accomplished with relatively archaic methods and had not created a dominant social group; nor had government policy reflected the interests of a dominant group whose strength was based on agricultural exploitation. The “coffee boom” created tremendous pressure for the commercial utilization of land. As a result communal and ejidal lands were abolished, and they quickly passed into private hands.1 The emergence of coffee as the dominant crop and of the oligarchic group that the boom supported helped consolidate the national government in El Salvador despite the lack of a unifying “national dictator” in the style of Mexico’s Porfirio Díaz, Guatemala’s Manuel Estrada Cabrera, or Venezuela’s Antonio Guzmán Blanco.

The crisis of the traditional system in El Salvador culminated in the “bourgeois revolution” of 1870. After that time “liberals” controlled the Salvadoran government. The cultivation of coffee entailed a modernization of the economy, and a preindustrial capitalist state emerged. The government was oligarchic because the principal leaders were recruited from a narrow social stratum which, in some cases, can be identified with two or three families: Araujo, Meléndez, and Quiñónez Molina. More important, they ruled in a manner that served the interests of the dominant group whether or not these coincided with the national interest. During these years the government was stable, since the economic base produced by the system of export agriculture afforded increased revenue. The average tenure of presidential incumbents increased during 1898–1930, and they left office peacefully (see Table 1-1). Finally, the ideology or value system that supported this form of political domination was “liberal.” The liberal Constitution of 1886—in force until 1944—provided legal justification and political legitimacy for a system that was relatively stable and successful until 1930.

Therefore, one can say that a preindustrial capitalist state has existed in El Salvador since the late nineteenth century. The powers of that state crystallized in a liberal-oligarchic government which evolved a political regime of markedly authoritarian character. Elements of this system included limited participation, decision making by elites, repression of discontent and of any attempt to organize by the popular classes, and a subordinate role for emerging urban middle-income groups. This system had only limited success, however, for, unlike in Colombia, where the typical unit of coffee production was of a small or intermediate size, in El Salvador the finca—a large estate—became the characteristic unit. These relatively few large estates also embraced satellite systems of subsistence agriculture that allowed for different forms of tenancy (small proprietors, arrendatarios [renters], and so forth) based on dependent relationships and, very frequently, coerced labor. In the Salvadoran case, the emergence of the finca as the basic unit of coffee production was not inevitable; it was simply a result of the manner in which capital and land became concentrated in a few hands. Control of the government and control of the process of land appropriation were the province of the same group.

The extent of oligarchic domination by the large cultivators of coffee becomes obvious in a closer observation of their role in the economy and government. The value of coffee exports increased from slightly over 2 million pesos in 1880 to 22.5 million in 1914. Between 1910 and 1914, coffee exports represented 86.9 percent of the average value of all exports, excluding gold and silver.2 Other export products, primarily gold and silver ores, were under foreign control and exploited through an “enclave” system. Therefore, they had very little impact on the socioeconomic system.

The connection between the coffee industry and government revenue was indirect. The government did not tax production or export but taxed instead the imports brought into the country and paid for with the foreign currencies earned by coffee. For the period 1870–1914 import duties contributed an average of 58.7 percent of government revenue, in contrast to an average of 40.5 percent during 1849–71.3

The political dominance of the coffee cultivators is reflected in the tariff policies of the governments. These were not intended to protect nascent industries that could grow to challenge the economic preeminence and political domination of the coffee oligarchy. In general, the symbiotic relationship between the government and the coffee industry operated in favor of the latter. During the period 1870-1914 government expenditures for infrastructure catered to the needs of the coffee establishment; military expenditures were reoriented from the defense of previously insecure borders against invasions by Honduras and Guatemala to the maintenance of order in the Salvadoran countryside. The government was able to pay back the public debt—the second largest category of public expenditures during 1870-1914—acquiring additional independence from social groups outside the oligarchy. Thus these groups had an even harder time making themselves felt on public policymaking, for not only was their access to policy decisions limited but their importance as fiscal contributors was reduced to relative insignificance.

Looking at organized interests, there is nothing comparable to the Asociación Cafetalera, the coffee growers’ association, which was under the control of the largest planters and represented their interests. Some have argued that this functioned as a second state or invisible government of El Salvador.4 This is a matter for conjecture, but there can be little doubt that government policy did serve the interests of the planters and that government leaders viewed this as one—if not the most important—objective of the government. Yet it would be inaccurate to limit this oligarchy to fourteen or some other such number of families, as many have done. To be sure, the economic resources of El Salvador have been managed by relatively few actors who, for the most part, have provided most of the investment capital.5 But one should not assume that this oligarchical group was perfectly homogenous and native. From the first, the coffee oligarchy incorporated some of the old latifundistas and merchant middlemen into its ranks, but a host of foreign immigrants also participated in the coffee boom and, later on, monopolized retail and wholesale trade.6 These immigrants ended up marrying into the “old money,” and therefore it may be better to speak of fourteen or quite a few more surnames that appear mixed in an endless stream of permutations.

Family connections are a crucial element in any attempt to understand the complexity and evolution of an oligarchical group. Whether by marriage to outsiders or as a consequence of family growth and the maturation of new generations, an oligarchical group is forced to diversify and, in so doing, to become more heterogeneous. In spite of their preference for labor-intensive methods and of their extravagant patterns of consumption, the coffee planters of El Salvador were a group of capitalists who understood their business. One finds them setting up their own banks to finance the operations of their fincas and beneficios (processing plants), trying to raise money for railway construction, or backing a government bond issue destined to subsidize one aspect of the business. They understood the requirements of their activities and the kinds of political mechanisms necessary to keep them going.

In comparison with Guatemala and Costa Rica, the conflict between merchant and planter appears muted in El Salvador, but there was some cleavage between the two, especially over such issues as the gold standard versus the silver standard, convertibility, devaluation, and the issuance of currency. In El Salvador, commercial banks—including the Banco Internacional (est. 1880), the Banco Particular (est. 1885), the Banco Occidental (est. 1889), and the Banco Agrícola Comercial (est. 1885)—were allowed to issue currency. It is difficult to tell which of these were controlled by the planters and which by the merchants, and which group benefited more. But in any case, the chaotic currency situation was not straightened out until the 1930s and the 1940s, when the Salvadoran monetary system was finally brought under public control. This division between the agricultural and business cliques seems to have existed from relatively soon after the consolidation of the liberal victory in 1870.

The appearance of some light industry in the early twentieth century did not alter the basic composition of the oligarchy or of the lower economic classes. The country remained a two-class society in which the peasants were effectively controlled, the urban working class was yet to appear, and middle-income groups were closely tied to the upper class. Any change in this structure would either have to originate outside it or be the result of an accumulation of pressures that the existing system of domination could no longer control.

The crisis of the oligarchical coffee republic of El Salvador came in 1931 as a result of demographic pressures on land tenure patterns, combined with a severe economic crisis and the activation of popular groups. Even though the state managed to survive, the nature of the government and of the regime was altered and a different system of political domination emerged. In a crisis of oligarchy it is no longer possible to form a legitimate government made up of members of the oligarchy and oriented to serve its interests exclusively. In the Salvadoran case, this did not mean that the coffee oligarchy disappeared as a social actor or that it lost most of its political power. If the oligarchy could no longer govern by itself, it remained the most influential among the few actors who were represented in the government. The crisis of the ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Map, Figures, and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- List of Acronyms

- Part 1: Salvadoran Reality

- Part 2: American Fantasies

- Appendix: Tables

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index of Names

- Index of Subjects