![]()

1

THE DEMISE OF PATRIARCHALISM

Until at least the mid-nineteenth century, Brazil was a rigidly hierarchical society bound together by ties of kinship and patronage.1 Its export economy (with its successive booms of sugar, gold and diamonds, rubber, and coffee—and to a lesser extent, cotton and cacao) empowered the great fazenderos, rural patriarchs whose control of land, labor, markets, and capital ensured their political hegemony as well as near absolute authority over their extended households. Coexisting with (and within) the large extended patriarchal families were the smaller nuclear families of the less prosperous as well as the consensual unions and female-headed households of the poor and the slave population. For them, survival—given the absence of any effective central political authority, the precarious and limited economy, and the total lack of social services—generally required allying with a powerful extended family (or parentela). In exchange for protection, economic security, and favors, landed potentates commanded loyalty, obedience, and service from dependent relatives, godchildren, needy friends, concubines, servants, tenants, free laborers, and slaves, as well as from their own wives and children.2

Children of the elite were reared to obey, even to the extent of accepting the right of the patriarch to choose their marriage partner. Romance was normally an irrelevant consideration; instead, elite families arranged marriages for their children (often with cousins or close relatives) with the aim of cementing political alliances and guarding property and status.3

Brazilian civil law (which until 1916 was an extension of the Philippine Code compiled in 1603 in Portugal) subordinated wives to their husbands, defining them as perpetual minors who were powerless to make final decisions about their children’s upbringing or even to administer their own property.4 Nineteenth-century travelers to Brazil painted a generally unflattering portrait of women of the elite. Frequently married off by their mid-teens to much older men, they were stereotyped as submissive, passive creatures whose cloistered domestic existence and superficial instruction (in playing the piano, singing, reciting poetry, dancing, and speaking a bit of French) made them exceedingly dull company. They quickly grew fat as a result of their indolent lives, deteriorated into stooped, wrinkled old matrons by the age of thirty (if they survived their many pregnancies), and were said to be characteristically bad tempered and abusive with their servants, especially with their husbands’ mulatto mistresses.5

As historians have since pointed out, this stereotype is surely overdrawn, given that elite women directed large, complex households with dozens of slaves and servants engaged in the production of food, clothing, and other household necessities. Moreover, to them fell the responsibility for providing health care, socializing children, and organizing family celebrations and religious rituals. And in exceptional cases, rich widows, with the authority they acquired as legal head of the family, successfully managed fazendas or family businesses and wielded formidable political and social power.6 Nevertheless, their example did not threaten the social norm of female seclusion, enforced (albeit with infractions) within the elite in order to guarantee the honor of the family and the racial purity of descendants.7

The vast majority of the population was separated from the elite not only by income and occupation but also by generally darker skin color, dress, and social customs. Legal marriage was a mark of status that the poor rarely achieved. For those without property to protect, consensual unions were the norm, illegitimacy rates were high, and female-headed households were very common. Female indolence and seclusion were impossible ideals. Beginning at very young ages, poor women labored in lowly manual occupations (as maids, cooks, wet nurses, laundresses, seamstresses, street vendors, or sometimes prostitutes) to eke out a marginal existence. And not only did their work take them into public spaces, but their income—however little—provided them a measure of autonomy.8

Brazil’s political system reflected and reinforced its hierarchical social order. With the Napoleonic invasion of the Iberian peninsula, the Portuguese royal court fled to Brazil, installing itself in Rio de Janeiro in 1808. After Brazil declared independence from Portugal in 1822, a constitutional monarchy reigned until 1889, providing the powerful planter aristocracy (at least from 1840 until the 1870s) with a legitimate centralized state that served its interests. Elections were indirect, and the franchise included less than 4 percent of the population: adult males who met income qualifications. Given that many eligible voters did not vote and that others (through loyalty or intimidation or in exchange for payments) cast their votes for the slate favored by the extended family on which they were dependent, the electorate was easily manipulated and electoral fraud was common. At the local level, political bosses (coronéis)—generally the heads of tightly knit extended families—controlled the political parties and dominated municipal government, monopolizing local officeholding and distributing the spoils to their clients.9

After midcentury, and especially after 1870, socioeconomic transformations gradually eroded the material bases of patriarchalism. The speeding up of the industrial revolution in Europe brought railroads and steamships to Brazil, created high demand for Brazil’s export crops, and offered unprecedented opportunities for profit, especially for landowners in the dynamic coffee-growing regions of western Sao Paulo. The rapid accumulation of capital allowed these coffee planters to accommodate to the ending of the slave trade by introducing modern technology to increase productivity and by gradually switching from slave labor to free immigrant labor. As southern European immigrants (whose passages were subsidized by the Sao Paulo and Brazilian governments) poured into the economically dynamic regions of the center-south, the internal market expanded. And as the cities of Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro mushroomed, wealthy coffee planters joined immigrant entrepreneurs in investing in infrastructure, banking, utilities, and the first consumer industries. Within these bustling, modernizing urban centers, the ascendant middle classes (of liberal professionals, bureaucrats, small entrepreneurs, shopkeepers, and clerical workers), along with artisans, industrial workers, and freed or runaway slaves, attacked traditional institutions and demanded reforms.10

In the face of rapid socioeconomic change, the formal institutions that had guaranteed social hierarchy collapsed. In May 1888, Parliament passed the Lei Aurea (Golden Law, which finally abolished slavery without indemnification) against only a few negative votes cast by representatives of indebted landowners in stagnant regions, and it was greeted with wild rejoicing in the nation’s city streets. On 15 November 1889, a military coup overthrew the monarch, whose base of support had been reduced to the most traditional sectors of the rural oligarchy. The victors—the military, wealthy Sao Paulo coffee planters, and the urban middle classes—established a republican government (the Old Republic, which lasted from 1889 to 1930). But the franchise expanded only minimally to include all literate males over the age of twenty-one, and the lives of the majority of Brazilians did not change significantly. In practice, because the urban middle classes constituted a small percentage of the nation’s population and had no base of support independent of the coffee export economy, they could be incorporated into the political system without undermining the power of the coffee elite, transforming the authoritarian character of the political system, or altering the neocolonial structure of the economy.11

While Brazil remained predominantly rural and dependent on the agro-export economy well into the twentieth century, its major cities grew at a much faster pace than the population as a whole, and they began to wield disproportionate political weight as well as cultural influence. Rio de Janeiro, after it became the seat of the Portuguese royal court in 1808, surpassed the northeastern cities of Salvador and Recife as Brazil’s largest and most cosmopolitan center. It benefited from the opening of Brazilian ports to all nations and the consequent expansion of international trade. Especially after midcentury, increasingly rapid accumulation of capital allowed for improvements in urban services and public works, as well as the acquisition of more of the trappings of “civilization”: the first national presses, new professional schools, a public library, theaters, coffeehouses, and elegant stores.12

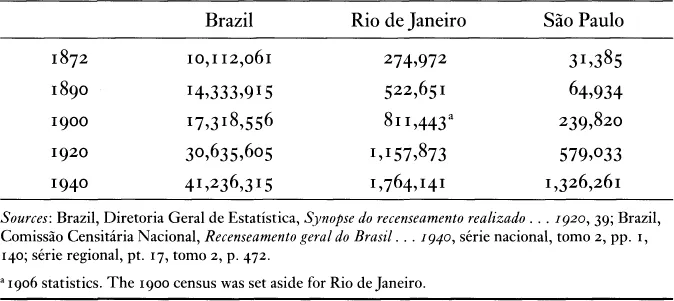

Rio remained the nation’s capital city after the formation of the Old Republic in 1889, and the liberal professionals who took over the city’s administration imposed (forcibly, over the protests of the poor) policies designed to remake both the urban space and its population in the image of Europe and according to Brazil’s new positivist motto, “order and progress.” Between 1902 and 1910, in a dramatic reconstruction of the center city, slums were demolished (and their poor, largely nonwhite inhabitants relocated) to make way for wide boulevards, large public buildings with magnificent Beaux Arts facades, and embellished parks and squares (as well as for “respectable,” generally white, families).13 Expanding commercial and employment opportunities attracted foreign immigrants and rural migrants, almost doubling the city’s population between 1872 and 1890 and more than doubling it again by 1920 (see table 1).

The city of Sao Paulo was even more quickly transformed from a muddy rural outpost to Brazil’s leading commercial and industrial metropolis. Between 1888 and 1928, more than two million European immigrants entered Sao Paulo, approximately half of whom had been provided a free passage in exchange for going to work on the coffee plantations.14 But many also migrated to the city, including those with sufficient capital to set themselves up as artisans, merchants, or entrepreneurs, as well as those who sought employment in the early textile, apparel, and food-processing industries. The population of Sao Paulo (city) more than doubled between 1872 and 1890, grew a spectacular 269 percent between 1890 and 1900, and grew again another 141 percent between 1900 and 1920 (see table 1). Immigrants provided cheap labor for the growing number of factories, which in turn supplied expanding local markets with manufactured goods. The value of the state’s industrial output more than doubled between 1905 and 1915. By 1920, Sao Paulo surpassed Rio de Janeiro as Brazil’s leading industrial center and began to rival Rio as an intellectual and cultural center.15

Table 1. Population of Brazil and the Cities of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, 1872–1940

Late-nineteenth-century urbanization dramatically increased opportunities for investment, employment, social mobility, and political mobilization—opportunities that in turn fostered transformations in consciousness and gradually loosened traditional patriarchal social relationships. Sons of planters who pursued urban careers escaped the tutelage of their fathers. Although their autonomy was compromised by their continuing dependence on patronage, their prestigious educational degrees, professional skills, and valuable political contacts gave them increasing leverage vis-à-vis their fathers. Moreover, liberal professionals and salaried bureaucrats no longer depended on receiving a substantial dowry from their wives’ families, since they did not need the agricultural land and other means of production that had been essential for setting up a household in colonial Brazil. Thus, although such men might still be seduced by the luxuries, status, and advantageous family connections that a “good” marriage could bring, they gained much more freedom to follow the inclinations of the heart. Propertied families, which had traditionally arranged marriages for sons and daughters, responded by gradually eliminating dowries by the end of the nineteenth century, both reflecting and contributing to the erosion of the patriarch’s power to control marriage choices. For elite women, marrying without a dowry meant total economic dependence on their husbands and a significant loss of leverage within the relationship. Nevertheless, they too gained greater freedom to choose (and responsibility to find) their own spouses. And propertyless women had a much greater chance of marrying legally.16

Legal reforms further reflected and contributed to the erosion of the power of the patriarch over sons and daughters. In 1831, the age of legal majority was lowered from twenty-five to twenty-one, thus allowing children to marry without parental permission earlier—a provision that children took advantage of only gradually, as they became more economically independent of parents. Early forced marriages were also restricted by the raising of the minimum age of marriage from twelve for girls and fourteen for boys to fourteen and sixteen in 1890 and sixteen and eighteen in 1916. And the 1890 civil marriage law forbade coerced marriages, specifying that windows had to remain open and doors unlocked when minors were married in private buildings.17

Accompanying the modernization of the economic infrastructure of the cities were notable changes in elite social customs. Garbage collection, underground sewers, street paving, gas lighting, and (especially) regular streetcar service allowed elite women to venture outside by the 1870s with a new degree of comfort, security, and ease. Their physical seclusion soon became an impossible and undesirable remnant of the past. Although always accompa...