![]()

VOLUME I

Introduction

![]()

Translator’s Note

Except when prefixed (Trans.), footnotes are from the original. Translations of quotations in the text are mine, except when the source title is given in English. Bibliographical details are presented in the original in a partial and unsystematic way, and wherever possible I have endeavoured to complete and standardize this information, a frequently difficult task, since the author uses his own translations of Marx. I wish to thank my colleagues Robert Gray, John Oakley and Adrian Rifkin for the advice and encouragement they have given me during the preparation of this project.

![]()

Preface

by Michel Trebitsch

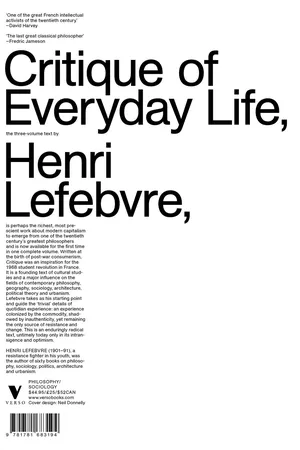

What a strange status this book has, and how strange its destiny has been. If Henri Lefebvre can be placed alongside Adorno, Bloch, Lukács or Marcuse as one of the main theoreticians of ‘Critical Marxism’, it is largely thanks to his Critique of Everyday Life (Critique de la vie quotidienne), a work which, though well known, is little appreciated. Perhaps this is because Lefebvre has something of the brilliant amateur craftsman about him, unable to cash in on his own inventions; something capricious, like a sower who casts his seeds to the wind without worrying about whether they will germinate. Or is it because of Lefebvre’s style, between flexibility and vagueness, where thinking is like strolling, where thinking is rhapsodic, as opposed to more permanent constructions, with their monolithic, reinforced, reassuring arguments, painstakingly built upon structures and models? His thought processes are like a limestone landscape with underground rivers which only become visible when they burst forth on the surface. Critique of Everyday Life is one such resurgence. One could even call it a triple resurgence, in that the 1947 volume was to be followed in 1962 by a second, Fondements d’une sociologie de la quotidienneté, and in 1981 by a third, De la modernité au modernisme (Pour une métaphilosophie du quotidien). At the chronological and theoretical intersection of his thinking about alienation and modernity, Critique of Everyday Life is a seminal text, drawn from the deepest levels of his intellectual roots, but also looking ahead to the main preoccupation of his post-war period. If we are to relocate it in Lefebvre’s thought as a whole, we will need to go upstream as far as La Conscience mystifiée (1936) and then back downstream as far as Introduction à la modernité (1962).

‘Henri Lefebvre or Living Philosophy’

The year 1947 was a splendid one for Henri Lefebvre: as well as Critique of Everyday Life, he published Logique formelle, logique dialectique, Marx et la liberté and Descartes in quick succession. This broadside was commented upon in the review La Pensée by one of the Communist Party’s rising young intellectuals, Jean Kanapa, who drew particular attention to the original and creative aspects of Critique of Everyday Life. With this book, wrote Kanapa, ‘philosophy no longer scorns the concrete and the everyday’. By making alienation ‘the key concept in the analysis of human situations since Marx’, Lefebvre was opening philosophy to action: taken in its Kantian sense, critique was not simply knowledge of everyday life, but knowledge of the means to transform it. Thus in Lefebvre Kanapa could celebrate ‘the most lucid proponent of living philosophy today’.1 Marginal before the war, heretical after the 1950s, in 1947 Lefebvre’s recognition by the Communist Party seems to have been at its peak, and it is tempting to see his prolific output in a political light. If we add L’Existentialisme, which appeared in 1946, and Pour connaǐtre la pensée de Marx and his best-seller Le Marxisme in the ‘Que sais-je?’ edition, both of which appeared in 1948, not to mention several articles, such as his ‘Introduction à l’esthétique’ which was a dry run for his 1953 Contribution à l’esthétique, then indeed, apart from the late 1960s, this was the most productive period in his career.2

Critique of Everyday Life thus appears to be a book with a precise date, and this date is both significant and equivocal. Drafted between August and December 1945, published in February 1947, according to the official publisher’s date, it reflected the optimism and new-found freedom of the Liberation, but appeared only a few weeks before the big freeze of the Cold War set in. ‘In the enthusiasm of the Liberation, it was hoped that soon life would be changed and the world transformed’, as Henri Lefebvre recalled in 1958 in his Foreword to the Second Edition. The year 1947 was pivotal, Janus-faced. It began in a mood of post-war euphoria, then, from March to September, with Truman’s policy of containment and Zhdanov’s theory of the division of the world into two camps, with the eviction of the Communist ministers in France and the launching of the Marshall Plan, in only a few months everything had been thrown in the balance, including the fate of the book itself. The impact was all the more brutal in that this hope for a radical break, for the beginning of a new life, had become combined with the myth of the Resistance, taking on an eschatological dimension of which the Communist Party (which also drew strength from the Soviet aura), was the principal beneficiary. With its talk of a ‘French Renaissance’ and a new cult of martyrs (Danielle Casanova, Gabriel Péri, Jacques Decour) orchestrated by Aragon its high priest, this ‘parti des 75,000 fusillés’ momentarily embodied both revolutionary promise and continuity with a national tradition stretching back from the Popular Front to 1798. Between 1945 and 1947 the PCF’s dominance was both political and ideological. Polling more than 28 per cent of the votes in the November 1946 general election, it appeared to have confirmed its place as the ‘first party of France’, without which no government coalition seemed possible. Its ideological hegemony, strengthened by the membership or active sympathy of numerous writers, artists and thinkers – Picasso, Joliot-Curie, Roger Vailland, Pierre Hervé – put Marxism at the centre of intellectual debate. Presenting itself as a ‘modern rationalism’ to challenge the ‘irrationalism’ and ‘obscurantism’ brought into disrepute by collaboration, its only rival was existentialism, which made its appearance in the intellectual arena in 1945. But existentialism also located itself with reference to Marxism, as we can see from the controversy which raged for so long in the pages of Les Temps Modernes and L’Esprit, and which began in that same year with Jean Beaufret’s articles in Confluences and above all with the argument between Sartre and Lefebvre in Action.3

In a way both were after the same quarry: Lefebvre’s pre-war themes of ‘the total man’ and his dialectic of the conceived and the lived were echoed by Sartre’s definition of existence as the reconciliation between thinking and living. At that time Lefebvre was certainly not unknown: from the beginning of the 1930s the books he wrote single-handedly or in collaboration with Norbert Guterman had established him as an original Marxist thinker. But his pre-war readership had remained limited, since philosophers were suspicious of Marxism and Marxists were suspicious of philosophy. Conversely, after 1945, he emerged as the most important expert on and vulgarizer of Marxism, as an entire generation of young intellectuals rushed to buy his ‘Que sais-je?’ on Marxism and the new printing of his little Dialectical Materialism of 1939; when he brought out L’Existentialisme, the Party saw him as the only Communist philosopher capable of stemming the influence of Sartre. With his experience as an elder member linking the pre-war and the post-war years and his image as a popularizer of Marxism, Henri Lefebvre could be slotted conveniently into a strategy by which the Party would exploit its political legitimacy to the full in order to impose the philosophical legitimacy of Marxism. He introduced Marxism to the Sorbonne, where he gave a series of lectures, on such topics as ‘the future of capitalism’ (March 1947) and ‘the contribution of Marxism to the teaching of philosophy’ (November). The latter was reported in La Pensée, ‘the review of modern rationalism’, in glowing terms:

Our friend Henri Lefebvre gave a brilliant demonstration of how dialectical materialism can and should rejuvenate and bring new life to the way philosophy is traditionally taught at university. We were expecting his lecture to be a success; the extent of that success took us by surprise. We had scheduled his lecture for the Amphithéâtre Richelieu, but in the event we had to use the Sorbonne’s Grand Amphitheatre, which was flooded with an expectant crowd of almost 2000 people, made up mostly of university staff, students and lycéens, who followed Henri Lefebvre’s brilliant talk with passionate attention and frequent applause.4

But if we take a closer look, things were less simple. The idyllic relationship between Henri Lefebvre and orthodoxy in 1947 was to be little more than a brief encounter, an illusory and ephemeral marriage of convenience that was not without its share of opportunism, and which was soon to be shattered by the watershed of Zhdanovism. And in any event, at the precise moment when, as he himself admitted, he had been ‘recognized as the best “philosopher” and French “theoretician” of the day’, Lefebvre’s material situation had become ‘appalling’, as he put it bluntly in September 1947 in a letter to his friend Norbert Guterman, whom he had just contacted again for the first time since the war.5 His poor health made the future look rather bleak, and for a while he was even out of work – a compounding difficulty as he already had numerous offspring to support, scattered over several different homes. He had been working for Radio-Toulouse, where Tristan Tzara, in charge of cultural broadcasts, had found him a job in 1945, but the change in the political climate forced him to step down, and also to give up the classes at the Ecole de guerre which General Gambier, whom he had met during his military service, had managed to secure for him. In fact when the war ended he had the grade of officer in the Forces françaises de l’intérieur in recognition for his Resistance work in the Toulouse region, but the Vichy administration had dismissed him from the teaching profession, and he was wary of asking to be reinstated for fear of being packed off to some provincial backwater. His frenzied rush to print, some of which was purely commissioned material, can be explained in part by his financial worries, though he was finally reinstated as a teacher and appointed in Toulouse in October 1947, and then seconded to the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) in 1948. Of the seven works he brought out between 1946 and 1948, six were with commercial publishers or beyond the purview of Communist publications. We should nevertheless note that although Critique of Everyday Life was published by Grasset, this was for distinctly political reasons. (The ‘Grasset affair’ was then at its height. Prosecuted for suspected collaboration, Grasset had just been acquitted by the investigative committee, but was still under attack from the Communist Party. After an unsuccessful attempt to bring in a compulsory purchase order in 1945, the Party backed a formula for control of Grasset dreamt up by René Jouglet and Francis Crémieux, who was in charge of the ‘Témoins’ collection, in which Lefebvre’s book appeared; the aim was to take over the house on a very broad basis, ‘with very “old school” Communists such as Pierre Hervé, leader writer with L’Humanité, but also independent personalities like Druon, Martin-Chauffier, Cassou’.)6

Though himself a Communist ‘of the old school’, Henri Lefebvre had not been integrated into the network of intellectuals ‘in the service of’ the Party who, with Aragon and several others as their focal point, were now dominating the stage. Indeed, according to his letters to Norbert Guterman, had this been proposed to him, he would have refused. Not that now and again he did not offer evidence of his allegiances, as for example when he took advantage of the campaign that had been mounted against ‘the traitor’ Nizan, his old associate of the 1920s, to settle some old scores post mortem in L’Existentialisme.7 It is also true that he joined the editorial committee of Nouvelle Critique, the ‘review of militant Marxism’ that was founded in 1948, but, in the words of Pierre Hervé, his presence at the journal was just ‘icing on the cake’, an intellectual gesture rather than a genuine creative force. His contributions were few, his main articles being responses to accusations of ‘Neo-Hegelianism’: in March 1949 he wrote an ‘Autocritique’ in which he denied having used his so-warmly received lecture of 1947 to present Marxism simply as a ‘contribution’ to philosophy.8 Behind all the circumlocutions, however, Henri Lefebvre held firm on three essential issues: the relations between Marxism and philosophy, those between Marxism and sociology, and the central role of the theory of alienation. Predictably, therefore, he very quickly began to fall out of favour. Between 1948 and 1957 he did not publish a single work of Marxist theory, unless one takes the view that his ‘literary’ studies on Diderot, Pascal, Musset and Rabelais were in fact indirect reflections on the dialectic of nature, alienation and the individual. In any case, from 1948 onwards, the Party put a stop to most of his projects.9 Logique formelle, logique dialectique, which Kanapa acclaimed in 1947 as a fundamental work, was to have been the first volume in a vast general treatise on Marxist philosophy, in a consciously academic format, to be called A la lumière du matérialisme dialectique. The second volume, Méthodologie des sciences, was not only drafted, but in March 1948 it was actually printed, only to be blocked by order of the Party directorate, which was then involved in defending Lysenkoism and ‘proletarian science’. Similarly, Lefebvre would not publish his Contribution à l’esthétique, drafted in 1949 from articles he had written in 1948, until 1953, and then it was only thanks to the subterfuge of a false quotation from Marx which was intended to reassure the Party censors.10 As for Critique of Everyday Life, it was to be followed by La Conscience privée, but this never saw the light of day. This final failure leads us back, however, to a much earlier moment in Lefebvre’s life; a moment which in turn will lead us by a series of regressions to the earliest moments of Lefebvre’s life as a philosopher.

Mystification: notes for a critique of everyday life

As we have attempted to demonstrate elsewhere, Henri Lefebvre’s originality, not to say marginality, lies in an unshakeable determination not only to reconcile Marxism and philosophy and to endow Marxism with philosophical status, but also to establish Marxism as critical theory, i.e. as both philosophy and supercession of philosophy.11 We should not be fooled by the expedient eulogies of a Kanapa: Critique of Everyday Life is an essential document on the construction of a critical Marxism of this kind, and completely out of line with official arguments. If we are to believe the note in which Henri Lefebvre links the book explicitly with the ones which preceded it, it would seem to belong to a vast master plan, one whose purpose was to ‘rediscover authentic Marxism’, defined as ‘the critical knowledge of everyday life’. He notes that the Morceaux choisis of Marx had drawn attention to economic fetishism, that La Conscience mystifiée had presented ‘the entire scope’ of modern man’s alienation, and that Dialectical Materialism had developed the notion of ‘the total man’, liberated from alienation and economic fetishism.12 Far ...