![]()

Chapter 1

Local Politics, Local Power

Governing Greater St. Louis, 1940–2000

The politics of property and race rest not just on the motives of local interests but also on the discriminatory opportunities opened by fragmented local governance. State and local law regarding incorporation, annexation, and consolidation vary wildly—but in most settings have made it easy to incorporate new localities on the City’s fringes.1 Beginning in the late nineteenth century, new municipalities, widely celebrated as a harbinger of economic growth and political self-determination, not only bounded “the city” but also began competing with it (and each other) for investment in real estate and commercial development. “By the early twentieth century suburbanites had begun carving up the metropolis,” urban historian Jon Teaford concludes, “and the states had handed them the knife.”2

These changes had enormous implications for residential patterns, taxation, and public goods in the nation’s growing cities. Metropolitan areas like St. Louis were relatively coherent economic, social, and ecological units. Labor markets, consumer markets, housing markets, and patterns of economic development spanned the urbanized region from the outer suburbs to the central city,3 but political regulation of those markets stopped and started again at each municipal boundary. Noting the proliferation of governmental units in suburban St. Louis County alone, one 1970 observer concluded that “Nearly all, by separate policies in zoning, subdivision regulation, and more subtle private action—maintain the white noose around the city.”4

Home Rules: Municipal Fragmentation in Greater St. Louis

The growth of American cities posed a practical and legal riddle. The Constitution vested original sovereignty in the states and remained silent on the political status of cities. By law and practice, the city was a quasi-public corporation, subject to regulation by the state but without “state” powers itself. “Localities could hardly call their souls their own,” one observer noted, “so tight were the fetters that bound them.” As of the mid-nineteenth century, cities could not levy taxes, go into debt, pursue local improvements, change the structure of local government, or (in many cases) even hire and pay their own staff without passing “special legislation” toward each end in the statehouse. As cities grew, this arrangement proved a headache for both local politicians (who deeply resented the meddling of state legislators) and state legislatures (which spent nearly half their time acting as “spasmodic city councils”).5

The solution, for local and state politicians alike, was “home rule”—a delegation of state powers to local governments. At their most basic, home rule provisions gave a state’s largest cities freedom from special legislation and control over the structure and administration of local government. At their most expansive, home rule provisions gave local governments (first cities meeting varying population thresholds, later counties) the power to shape their own charters, enter into contracts, tax local residents, go into debt, zone and annex land, and provide a range of local services.6 In Missouri and elsewhere, the practice of home rule was pursued and won for an idealized city—a sort of Florentine or Roman city-state representing a diverse economic and demographic base, a metropolitan anchor for a larger region, and a “more or less natural unit of government.”7 But cities changed. As home rule ceded greater authority to local governments, it also made it possible for fragments of the metropolis to incorporate their own governments. The result was not just cities with some autonomy from state rule but proliferating suburbs with autonomy from the central city and from each other. Over its modern history, St. Louis has, like most American metropolitan areas, been governed by a patchwork of states, counties, incorporated municipalities, school districts, special districts, and public authorities.

Missouri and St. Louis were precocious innovators on the home rule front. In the wake of the Civil War, urban interests felt increasingly underrepresented (and their interests often ignored) by both the state legislature and St. Louis County itself. State and rural interests, for their part, saw the administration of cities swallowing more and more legislative resources and attention. The result, sealed in the state’s 1876 constitutional convention, was twofold. First, the state moved to tidy up its own rules for local governance—setting local debt limits, proscribing the passage of “special laws” in the statehouse, and establishing a classification system for villages, towns, and cities. Second, it gave cities the option of adopting charters of self-government—a provision (limited at the time to cities with populations over 100,000) written expressly for the city of St. Louis.8 Given this opening, the city adopted its present-day boundaries and opted for formal separation from St. Louis County. Because the city was no longer located in a county, the new charter, in effect, made it its own county—resulting in a hybrid government with both municipal (police power) and county (property assessment, courts) responsibilities.9

While Missouri’s home rule provision was designed and passed for the city of St. Louis, its restrictive population threshold fell quickly: by 1945 home rule had become an option for any Missouri city with over 5,000 residents and any county with assessed property value exceeding $4,500,000. Indeed, since 1876, the importance of home rule has rested less on the autonomy it granted the city of St. Louis than on the opportunity it has afforded surrounding communities, especially those multiplying west of the City limits, to poach St. Louis of its wealth and resources. Under the 1876 constitution, no city or town could incorporate within two miles of the corporate limits of another city in the same county. But since St. Louis was no longer in St. Louis County, Missouri suburbs could crowd along the City limits. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, bordering towns thrived on “picture shows, gambling devices, vaudeville performances advertised under suggestive titles, … roulette wheels, shell games, and other fraudulent schemes”—all aimed at an urban audience but located beyond the reach of the City’s police power.10 As residential pressures and prospects reached the City edges, so did the vice squad, and the suburbs made quite a different appeal: no longer unregulated outposts of the City, they now offered a haven from it.

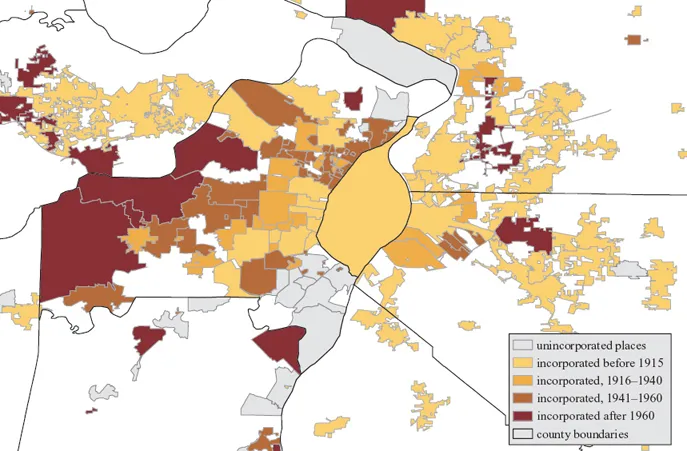

Early on, the conventional pattern of urban growth—annexation of outlying, often industrial, suburbs—was blocked in St. Louis, whose western border was sealed in 1876 and whose industrial suburbs were largely on the Illinois side of the river. New municipal incorporation began early in the twentieth century, but was concentrated in the decades after World War II (see Map 1.1). St. Louis County claimed six incorporated municipalities in 1900 and only twelve more by 1930—but that number had more than doubled by 1940 and doubled again by 1950.11 When St. Louis County officials took note of this “epidemic” of incorporation in 1955, fully half of the County’s municipalities were less than 12 years old. The driving force behind this, of course, was the rapid residential development of St. Louis County, which added over 225,000 single-family homes between 1950 and 2000. Municipal incorporation on the Illinois side, by contrast, was settled much earlier. And many of the cities and towns in the metro area’s more remote Missouri counties were older industrial or agricultural centers overtaken by (but predating) metropolitan sprawl.12

In St. Louis County, the central inner-ring suburbs were essentially extensions of the City, and reflected the same patterns of land use (mixed-density housing in University City, commercial development in Clayton, industry in Wellston) as those parts of the City they bordered. Elsewhere, the proliferation of new cities and towns was driven by the pace of residential subdivision and development. Much of the County’s postwar housing stock was erected in subdivisions in unincorporated areas of the County. The character of these suburbs was determined by the terms and standards of private construction and realty (including house and lot size and deed restrictions). Residents had little interest in attaching themselves to existing municipalities and often pursued small-scale incorporation as a means of sustaining local standards. City planners (most notably Harland Bartholomew and Associates) routinely discouraged their St. Louis County clients from annexing new territory—arguing instead that smaller municipal units (population 8,000–10,000) were sufficient to provide local services and necessary to avoid the threats posed by mixed density or use. The result, noted as early as the late 1920s, was a “considerable number of small communities,” each “separate from the metropolitan city and … aloof from its neighbor.”13

New municipal incorporations rested on a variety of motives: University City began as a planned “city of the future” extension of the 1904 World’s Fair. Peerless Park (disincorporated in 1999) was, for most of its history, noted for its disinclination to regulate the sale of fireworks. St. Ann was established as a Catholic enclave. The city of Berkeley grew out of a dispute over school district boundaries with neighboring Kinloch (the lone black enclave in the County): when white residents failed to sustain school segregation by dividing the school district, they created a new town in 1937 instead. Kinloch itself incorporated in 1948, but its tax base was so meager it moved to disincorporate a year later. Black Jack (as we shall see in Chapter 3) was hastily formed in 1970 to stave off a mixed-income housing project. The sprawling west County municipality of Wildwood (incorporated 1995) was driven largely by fears that St. Louis County was not willing to sustain large-lot single-family residential development.14 By and large, suburban municipalities existed to sustain local residential standards and patterns: “The prime purpose in forming the village,” the founders of Moline Acres underscored, “was to maintain a residential area … we were quite anxious to get a zoning ordinance on the books.” The provision of local services and police power protections was often an afterthought. Smaller communities contracted with the County or their neighboring towns for most services. Of 86 St. Louis County municipalities surveyed in 1957, only 33 had more than one paid police officer, only 17 had full-time fire personnel, and only 2 (Clayton and University City) had their own health departments.15

Map 1.1. Municipal incorporation in greater St. Louis, 1915–2000. Illinois and Missouri Secretaries of State (2000 boundaries).

The pattern (and folly) of patchwork municipal incorporation in St. Louis County was underscored by the tiny village of Champ, incorporated in 1959. Champ’s master-mind, Bill Bangert, wanted to build a domed stadium in St. Louis County but needed a municipal sponsor to qualify for industrial revenue bond financing. The County rebuffed the initial incorporation proposal but acceded to a more modest version: At its founding, Champ boasted 7 houses and a church (at the 2000 census it had 4 houses and a population of 12). The stadium plan passed the Missouri legislature but was vetoed by the governor. Undeterred, Bangert pressed to annex 3,000 acres of the Missouri Bottoms for an industrial park—promising to run the expanded city with a board of commissioners elected by commercial tenants on a one-acre per vote basis “to help eliminate municipal harassment of industry.” The County dug in against this land grab, challenging not only the annexation plans but the validity of Champ’s original incorporation. The case dragged on through the 1960s, the Missouri Supreme Court eventually upholding the original incorporation but quashing the annexation plans.16

Most commonly, especially in the decades surrounding World War II, subdivisions incorporated as a means of staving off annexation by their neighbors. Resident of Clayton had considered incorporation off and on in the early twentieth century but only formalized their plans (1913) when University City began exploring annexation. This pattern became even more common after 1929, when established cities began looking to weather the fiscal crisis of the Great Depression by padding their property tax base. Des Peres residents, for example, had long resisted the expectations (and new taxes) of municipal status but quickly circulated an incorporation petition (1934) to stem the plans of Kirkwood to push its boundaries (and those of its school district) north. Members of the Crestwood Subdivision Association, fearing annexation by neighboring Oakland, pressed for the creation of the city of Crestwood (1947). Moline Acres was established in 1949 to stave off annexation by Jennings or Bellefontaine Neighbors.17

Much the same pattern held in the latter half of the century, although the constraints and motives shifted. The 1945 Missouri constitution and a subsequent home rule charter gave St. Louis County itself a new standing as a corporate body. In 1951, the St. Louis County Council tried to discourage new incorporations by requiring that detailed budgetary planning accompany any new petition. But the courts left little doubt that the County was required to approve any reasonable petition and expressly “not authorized to deny incorporation … merely because it decides that no more municipalities are advisable.” In 1953, the state made annexation more difficult by establishing a county-level approval process (administered by a new boundary commission) and pressing annexing governments to demonstrate that annexation was a natural or reasonable extension of their boundaries. Under these new (Sawyer Act) rules, the pace of new incorporations slowed but local interests could forestall annexation just by filing a petition with the county.18

These new rules proved especially important in St. Louis County, which waged a monotonous battle with municipalities looking to gobble up “unincorporated” county parcels along their borders. One such skirmish was fought over a roughly 300-acre parcel west of Olivette and north of Creve Coeur. The land was substantially developed for industrial use (including GE and Monsanto) and already serviced by a combination of private and County infrastructure. In 1957 Creve Coeur proposed annexation, conceding at the time that its goal was to create a buffer between existing residential development and commercial development on County land—while at the same time laying claim to a large commercial tax base. The courts summarily rejected the annexation, noting that Creve Coeur (which had no fire department, trash collection, or city hall) off...