![]()

PART II

Representation Beyond Elections

![]()

CHAPTER 7

The Paradox of Voting—for Republicans:

Economic Inequality, Political

Organization, and the American Voter

Jacob S. Hacker and Paul Pierson

Over the last generation, Americans at the top of the economic ladder have pulled sharply away from everyone else. The share of pretax income earned by the richest 1 percent of households more than doubled, from 9 percent in 1970 to over 23 percent on the eve of the 2008 financial crisis (Piketty and Saez 2003; Saez 2012). Gains higher up the ladder have been more spectacular still, even as earnings growth for most Americans has slowed (Hacker and Pierson 2010a). At the same time, the Republican Party has become more conservative on economic issues. According to a widely used left-right index based on congressional roll-call votes, Republicans in the House of Representatives have become dramatically more conservative, on average, since the 1970s, while Republicans in the Senate have become substantially more conservative. The average Democrat in Congress, by contrast, has moved only modestly to the left (calculated from Poole and Rosenthal 2012).

A long line of democratic theorists, as well as most political science models of redistribution, would predict that under these circumstances, non-rich voters would shift to the Democrats in support of greater government efforts to tackle inequality (e.g., Tocqueville 2000 [1835]; Meltzer and Richard 1981). With the GOP moving right as less affluent voters moved left, the Republican Party would lose ground to the Democratic Party. Yet the GOP has not only gained ground over this period, shifting to essential parity with Democrats in the electoral arena, but also picked up support from a crucial downscale component of the Democrats’ coalition, the white working class. Why? Why has there not been a broader electoral backlash against the more conservative party in an era of rising inequality?

Most commentators on this question have focused on voters and values. Thomas Frank, in his bestselling 2004 book, What’s the Matter with Kansas?—a bible among despairing Democrats after George W. Bush’s reelection—argued that Republicans had skillfully used cultural wedge issues to attract working-class support in an era in which the working class had fallen farther and farther behind the well off. From the other side of the political spectrum, New York Times columnist David Brooks (2001) countered that working-class voters had turned against a Democratic Party increasingly beholden to wealthy liberal elites. Popular commentary has portrayed an enduring divide in which values trump class: a less affluent Red America filled with NASCAR-loving, gun-toting GOP traditionalists who oppose gay marriage versus a richer Blue America filled with sushi-loving, New Yorker-reading Democratic cosmopolitans. In this conventional view, voters are the prime movers, and it is their failure to rise up and demand action that is taken as evidence of either their lack of real interest (Brooks) or GOP manipulation of their conservative social values (Frank).

In this chapter, we present a quite different view—one focused on political organizations as well as voters, and on perceptions (and misperceptions) of inequality and government policy as well as voter ideology. We show that while voters are key players, the American political game has been dominated by political elites, in part because the organizations that once gave voters information and clout have eroded. As a result, growing elite polarization and class stratification have, ironically, occurred alongside a profound demobilization of American voters around issues of inequality. Contrary to the conventional view, the source of this demobilization is organizational far more than it is attitudinal. That is, it is rooted in structural shifts in the nature of American politics—from the rise in business lobbying to the decline of organized labor and large-scale voluntary associations—more than it is based on changes in the fundamental beliefs of voters. These organizational changes, however, have helped spark shifts in voters’ views that have reinforced the tilt of American politics away from less affluent voters.

This argument has crucial implications for how we understand what elections can and should do. Over the last generation, students of American politics have almost single-mindedly built their investigations around a view that we call “politics as electoral spectacle,” in which public opinion and elections are seen as the driving force behind politicians’ positions and, ultimately, public policy. This perspective has enhanced our understanding of elections, opinion, and votes in Congress. But it is gravely deficient for understanding the paradox of less affluent voters’ support for the GOP in an era of runaway inequality. In place of this standard narrative, we sketch out an alternative perspective—“politics as organized combat”—that emphasizes the role of organized interests in mediating the ability of voters to become aware of and respond to rising inequality (Hacker and Pierson 2010b).

Elections matter, of course. But without organizations bringing Americans into politics and informing them about their interests and issues that affect them, free and fair elections are no guarantee that the voices of citizens will be heard. It is the organizational transformation of American politics, rather than changes in voter attitudes or partisan attachments, that must be the starting point for any convincing analysis of voters’ response to rising inequality, as well as any effective prescription for political reform.

Voting Against Self Interest?

Discussion of the changing voting patterns of less affluent voters has emphasized the shifting allegiances of the “white working class.” This is a restrictive focus in some respects, as the white working class has declined as a share of the electorate in tandem with rising levels of education and professionalization. But it has a number of advantages as well. Perhaps most important for us here, long-term change in the white working class’s voting allegiances is very difficult to explain with short-term fluctuations in the performance of the economy, such as those that lie at the heart of many political-business cycle models that focus on the effects of fiscal and monetary policy in election years.

Another crucial advantage of examining the voting patterns of the white working class is that they are the subject of a large and growing body of research in political science and sociology that has addressed critical difficulties of measurement and definition (e.g., Kenworthy et al. 2007; Abramowitz and Teixeira 2008; Bartels 2008). Much of the debate over whether the white working class has abandoned the Democratic Party revolves around defining the white working class itself. The basic issue is whether working-class status is principally defined by family income or whether it reflects some alternative or additional characteristics (such as self-identification as “working class” or one’s level of educational achievement). Even if income is taken as the marker, there remains the question of how well off someone has to be to be considered “working class.” Larry Bartels (2008), for instance, has argued that the popular concern over the Democrats’ loss of working-class support is misplaced. Defining the “white working class” as white voters in the lowest third of the national income distribution (below $35,000 in family income in 2004), Bartels argues that there has indeed been a shift away from the Democratic Party toward the Republican Party, but that it is “entirely attributable to the demise of the Solid South as a bastion of Democratic allegiance”; outside the South, low-income whites have not moved toward the Republican Party at all (Bartels 2008: 75).

Bartels’s argument is a useful reminder that we must take account of the suppression of partisan competition in the South prior to the civil rights revolution. Some decline in Democratic identification was inevitable as the South became electorally competitive and conservative voters moved into the Republican camp. Nonetheless, Bartels’s interpretation of his findings and definition of the white working class are both open to serious challenge.

For starters, given how sharp the rise in economic inequality has been, the expectation from models of self-interested voting has to be that lower-income voters would have moved into the Democratic fold, especially given the sharp move to the right of the GOP over this period. Over the last generation, we have seen a massive increase in inequality. The typical American voter has fallen farther and farther behind the rich. If people care about their relative economic standing in the way standard political-economic models suggest they should (e.g., Romer 1975; Meltzer and Richard 1981; Roberts 1977), working-class voters should have shifted decidedly to the left. The implications of this would depend, of course, on the position of the two parties—but with the GOP becoming much more conservative on economic issues and the Democrats only modestly more liberal, the expected outcome would be a shift toward the Democratic Party. Indeed, given how sharply skewed income growth has been, the shift should have occurred among the middle (and even upper-middle) class as well as the working class.

Furthermore, Bartels’s definition of the white working class is far too narrow. By his standard of $35,000 in family income, any family with at least one full-time worker with an hourly wage greater than about $17 would not be considered working class, nor would a family with two full-time workers earning in excess of about $8.50 an hour. By comparison, the average unionized blue-collar job paid more than $22 an hour in 2003 (Abramowitz and Teixeira 2008: 13). Because Bartels uses national income distribution rather than distribution among whites, moreover, he classifies only about 23 percent of white voters (rather than a full third) as “working class.”

In the rest of this chapter, we follow political sociologist Lane Kenworthy in defining the white working class as whites who tell pollsters that they belong to the working class (so-called self identification)—a group that comprised around four in ten whites (Kenworthy et al. 2007). Analyses that use educational level (for example, less than college degree) or occupation (blue collar or manual worker) end up with similar results. All these definitions hone in on a set of voters for whom the paradox of siding with Republicans in an era of rising inequality is particularly acute. Once the backbone of the Democratic Party, white working-class voters have clearly been on the losing end of the dramatic rise in economic inequality. Their shifting allegiances thus provide a revealing window into the forces behind the lack of broad voter backlash against the GOP in the era of winner-take-all inequality.

Compared with defining the white working class, it might seem easy to define “support for Democrats.” Just look at how people vote, particularly in presidential elections. Yet votes in any given election rest heavily on the personality and positions of the particular candidate on the ballot, as well as whether that candidate is an incumbent. For these reasons, the partisan identification of voters is a stronger measure of support for a party and its ideology, if, admittedly, one more divorced from actual choices at the ballot box. Party ID represents a relatively stable characteristic of voters that powerfully shapes not just how people vote—for lower-level offices as well as President—but also how they view the world.

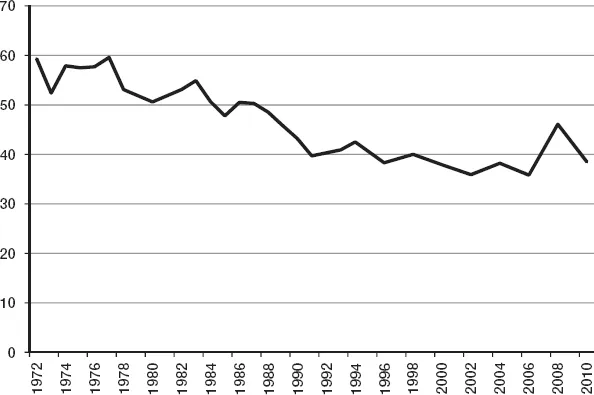

Various definitions of party ID are available, but, thankfully again, the definition does not affect the long-term trend: working-class white voters are less likely to support the Democrats and more likely to support Republicans than they were a generation ago. Figure 1, based on the work of Kenworthy and his colleagues (2007), shows the basic story: in the 1970s, roughly 60 percent of whites who identified as working class said they were Democrats (strong partisans, weak partisans, and independents leaning Democratic). By the 1990s, the share was down to around 40 percent. Using these data, Kenworthy runs through and dismisses a number of common explanations for the decline. The decline did not just occur in the South, but was broad-based. Nor was it just a product of general party disaffiliation, as Republican identification increased. There has been “a genuine decline of substantial magnitude in Democratic identification among working-class whites since the mid 1970s” (Kenworthy et al. 2007: 9). Although the white working class shifted back to the Democrats in 2008, after Kenworthy’s paper appeared, by 2010 their support for Democrats had returned to pre-recession levels.

Figure 7.1. Share of white working class identifying with the Democratic Party. Kenworthy et al. 2007 analysis of General Social Survey, updated by authors.

Class Dismissed?

Whenever a model of the world and reality diverge, it is worth reexamining the model—not least because doing so makes clear exactly which links in the chain of logic are weakest. The standard view that less affluent voters will vote for greater redistribution when inequality increases requires that voters conceive of their economic interests in a specific way; that they put their economic interests above other concerns (for example, their social values); and that they do not have trouble translating their economic interests into policy and partisan preferences. Each link in this chain could break.

To many observers of American politics, the first link in the chain—how voters conceive of their interests—is most vulnerable. Americans do not harbor egalitarian sentiments, skeptics say. Or they insist that all Americans believe they will be rich someday and thus do not believe in redistribution (for the general argument about redistribution and upward mobility, see Benabou and Ok 2001).

Compared with citizens of other rich democracies, Americans do stand out as generally less supportive of government efforts to redistribute income, though the differences are often small. Yet the main message of comparative opinion research is that the United States is not a clear outlier with regard to many attitudes regarding inequality (Osberg and Smeeding 2006). Americans are broadly concerned about inequality of income, wealth, and opportunity, and surprisingly (given how much we hear about their in-egalitarianism), generally supportive of concrete measures to address inequality, insecurity, and hardship (Page and Jacobs 2009).

The key question, in any case, is not whether Americans have distinctive beliefs about redistribution, but whether those beliefs have substantially changed during the era of rising inequality. The evidence is strong they have not. Whether the questions concern basic attitudes toward economic equality or beliefs in upward mobility, the story of the last generation is far more one of stability than of change (Hacker and Pierson 2005).

And to the extent that it is a story of change, the change has probably been toward greater concern about inequality, not less. Indeed, according to data from the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP), administered by the General Social Survey in the United States and similar national survey institutions in countries across the globe, Americans grew more concerned about inequality in the United States between 1987 and 1999 (Kenworthy and McCall 2007).

While Americans do believe strongly that upward mobility is possible in the United States, they are also more realistic than they are often given credit for about their own prospects. The poll results in Table 7.1 suggest that Americans have not be...